Chapter 11 - Standards: An Enabling Institution 1979-1984

11.3 DIX (Digital Equipment Corporation, Intel, and Xerox): 1979 - 1980

Over the summer of 1979, Metcalfe continued to shepherd the possibility of three-way cooperation among Xerox, DEC, and Intel to commercialize Ethernet. Finally, that fall, the three firms met at the Boxborough Sheraton, Boxborough, MA. Acknowledging Metcalfe’s essential role, they invited him to the pre-meeting dinner. The following day the technical teams of the three companies met without marketing people or Metcalfe. Slighted not in the least, Metcalfe turned his attention to how his fledgling 3Com could fund building products that would conform to the technical specifications he expected DEC, Intel and Xerox (DIX) to negotiate and then publish.

To avoid antitrust legal complications, the DIX members had to agree to place the results of their collaboration in the public domain for the purpose of creating a standard. On the surface, the formation of Project IEEE 802 would have seemed an ideal means to make Ethernet a standard; if not the standard. However Graube’s bias against any corporation usurping the authority of Comittee 802 set the two efforts on a collision course.

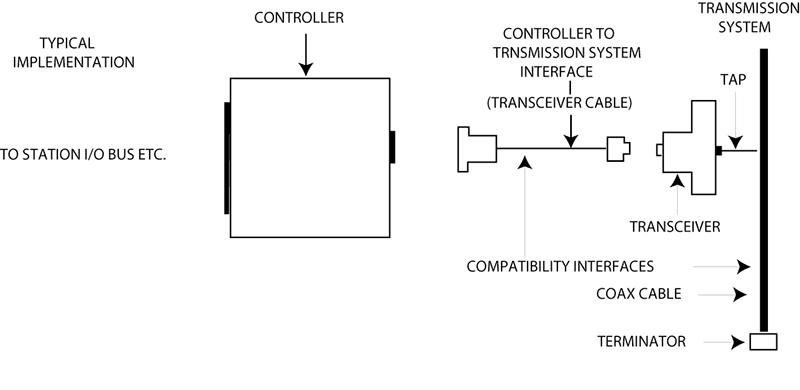

Agreeing to cooperate did not mean that the DIX members shared a common view of what the Ethernet standard should be. In fact, their differences often gave rise to tensions straining the collaboration to the breaking point. But each time, the strength of their collective commitment to the commercial opportunities of local area networking prevailed and they resolved their differences. (The description and lexicon of Ethernet at the time is seen in Exhibit 11.3.1 Ethernet Model.)

Exhibit 11.3.1 Ethernet Model

Each company’s technical team came with their own prejudices, competencies, and requirements. Kaufman of Intel remembers:

The issues really were cabling and controller chips. There was no problem in making the chips run at 10 megahertz, and there were lots of issues about cabling, and I think what pushed up the cost most, in the early years, was Xerox and DEC’s insistence of having coax, because they were interested in all the very real problems of installing this stuff and making it work and making it reliable. Whereas the rest of us were much more hackers, we were willing to pull anything if it would work. There were debates about could anybody build a transceiver that would really work at any speed reliably despite the existence proof of what had been running at PARC. This was a black art by one guy in a closet, and a lot of theoretical work was spent by people on ‘What should a transceiver do and could it work?’

Liddle of Xerox, on the other hand, remembers:

We thought that the Xerox design was conservative and then those guys jacked it further up, but that was all right, because they wanted it to be reliable. So it was a very tight piece of engineering that was done!

While work progressed, the central issue of transferring proprietary, patented, technology from Xerox to DEC and INTEL remained unsolved. Xerox had flourished controlling its technology. From the beginning, Xerox’s desires to keep PARC’s innovations secret suggested Xerox might not agree to license Ethernet. Nevertheless, work progressed under the leadership of Liddle, Kaufman and Dave Rodgers of DEC.

After intense negotiations, the three companies decided to execute two agreements: one between Xerox and DEC and the other between Xerox and Intel. There would be no three-way agreement, although the two agreements were linked by conditions. Liddle recalls:

All three parties had to agree to implement this product as a standard for their future products. It didn’t have to be their only network they used, but they all had to agree to implement it and support it. Xerox proposed to license, for one thousand dollars each, the Ethernet technology and to reserve for them a block of addresses and so forth. Intel had to agree to manufacture an integrated circuit chip set to implement the protocols and control. Digital had to agree to design and manufacture a low-cost transceiver.

Liddle then faced the challenge of securing the agreement of Xerox. The strength of his argument rested in his belief that it was in the best interests of Xerox to license the technology and that DEC and Intel were ideal organizations to partner with. Fortunately, Peter McCullough, the President, believed Xerox should creatively use its technology to acquire technology and commitments from others. When Liddle made his presentation to McCullough, he remembers McCullough quickly saying:

What a great idea. Trading the rights to this patent for improvements and all that, and their commitment to make parts, and then use it as a standard. What a great idea.

By now, word of DIX had spread. Other companies wanted to participate. Yet more participants might complicate the process more than help. Gordon Bell of DEC remembers:

I got calls from a bunch of places wanting to be part of the design team. Intel was pressuring me. Intel sent Olivetti after me, and I talked to somebody at Olivetti and he said: ‘We want to be part of that.’ I said: ‘No way. We’ve got eight of the best people I know designing it now. Any more people will hurt it. We’ve got plenty of people inside of DEC that would like to be part of it. I’m sure Intel’s got a lot of people. Xerox could probably drum up people. This thing is going so well. Let’s not mess it up. You can comment once its available.’

Kaufman, on the other hand, sought to stimulate as much support as possible. Intel wanted ready customers for its new chip.

We worked, trying to influence a lot of other companies, because for us, the whole goal was, besides some altruistic one about making communications work and advancing the state of the art, to generate customers who were ready for the chips we were going to build.

One of the prized potential customers for Intel was Hewlett Packard (HP). Every couple of months Kaufman would have lunch with Dave Crocket, head of strategy and planning for HP. In addition to bemoaning the difficulties of trying to make strategies in their organizations, they discussed technological developments including networking. HP had multiple networking standards being developed and Crocket believed that the groups would be more likely to support an external standard than to trade their own standard for another group’s. He pushed Ethernet as the best solution.

Intel also wanted to make the Ethernet chip as complex as possible. Kaufman:

We drove the Ethernet controller chip to make it a tremendously complex chip that did a lot of work, because that was Intel’s advantage. If we could set the high-water mark that everybody else had to come up to have a viable controller, there would be something that we did best, we’d take advantage of our ability. So, that first chip really was a whole computer.

Standing against adding more participants and making a more complex Ethernet chip was the risk of being left at the altar by the authority of Committee 802 to define a standard. With the DIX collaboration still far from agreement among themselves, their concern turned to the upcoming Committee 802 meeting and fears that momentum might build for an alternative technology. To forestall precipitous action by Committee 802, they decided to announce just prior to the May meeting that they would publish their standard in September.

Liddle remembers hammering out the press release to have been “harder to accomplish than the original contract.”