Chapter 2 - Background

2.4 Crisis

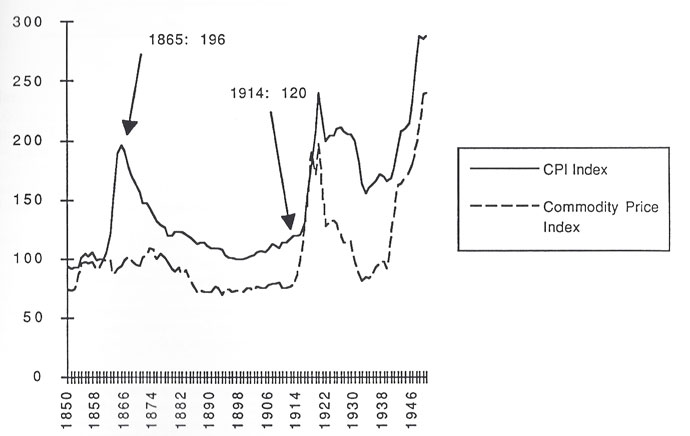

In 1873, the world economy fell victim to the Great Depression. For an interminable twenty-three years, economic life seemed as if on a slippery slope to a destiny neither understood, nor to be escaped. It was little different in America. A first depression began in 1873 and lasted to 1879 – the longest in history. Deflation also set in, lasting twenty years until 1893, when prices were 64% of those of 1873, a free-fall of 36%. (See Exhibit 2.2 Deflation 1850-1950) The many small businesses that constituted competitive capitalism were being shown to be what they really were – small, local monopolies. For those that could not adapt to the new competitive conditions, it meant failure, and, between 1869 and 1879, 64,000, or 15%, of them did. (See Exhibit 2.3 Business Concerns) Paradoxically, 274,000 new businesses formed, a decade over decade growth rate of an astounding 222%. An economy in historic aggregate decline, and, simultaneously, unprecedented churning and new growth among businesses. What were owner-managers of the businesses of competitive capitalism to do? And given the institutional constraints of state-based control, uncertain corporation rights, and the lack of capital markets, what could they do? Out of this caldron of uncertainty and change emerged corporate capitalism – an economy of Big Business and Big Government.

Exhibit 2.2 Deflation 1850-1950

The American depression that began in 1873 happened suddenly. In September, railroads’ defaulted on debt payments and caused a financial panic.106 Speculation in railroad securities collapsed, soon followed by the failures of prominent business firms, brokerages, and banks; the stock exchange closed for ten days; banks suspended currency payments; gold reached a new low by year-end, and silver was demonetized.107 The years to follow were described by those there as a depression and disturbance of industry.108 Economic growth that had seemed so certain, when simply left to the competitive forces of natural liberty, became elusive. Using change in Gross National Product as proxy for economic growth, robust growth of 5.58 percent in the late 1860’s slowed to 2.55 percent by the end of the depression in the period 1893 to 1897 – the first “industrial” depression. (See Exhibit 2.4 Growth in GNP Per Annum)

Exhibit 2.3 Business Concerns (In thousands)

| Year | Total factories | Total business concerns | Total business concerns (not factories) | Increase in total business concerns (not factories) | Business failures of the last 10 years | Business churning of the last 10 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1859 | 140 | 230 | 90 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 1869 | 252 | 427 | 175 | 85 | 24 | 109 |

| 1879 | 253 | 702 | 449 | 274 | 44 | 338 |

| 1889 | 355 | 1051 | 696 | 247 | 89 | 336 |

| 1899 | 207 | 1148 | 941 | 245 | 126 | 371 |

Source: Statistical Abstract of the United States, no. 721, p. 745.

Contributing to the severity of the depression of 1873 was the reversal in Federal spending following the Civil War. In 1859, Federal debt totaled $58 million; in 1866, $2,756 million. The Federal Government, in essence, borrowed more than $2.5 billion prosecuting the war.109 The money sloshed around in the economy until extracted – the government began paying down the national debt in 1867, and did so every year but one until 1879 – or until the exchange needs of a market economy used the money.110 Once the Civil War money transient dampened, the drastically reduced demand for goods and services by the Government meant supply chased less demand, and so prices dropped. (The economies between 1869-1873 had average GNP of $6.5 billion; the increases in the national debt in the two years 1865 and 1866 were each more than $600 million, 10% of the then economies.)111

Contributing to the decline of prices as well was the telegraph. The telegraph had been seen for the change agent it truly was as early as 1847: “operations are made in one day with its aid, by repeated communications, which could not be done in from two to four weeks by mail – enabling [businessmen] to make purchases and sales which otherwise would be of no benefit to them, in consequence of length of time consumed in negotiation.”112 In 1869, 8 million telegraph messages were being sent and received. By 1879, the number had jumped to 25 million.113 Information riding lightning made for drastically more transactions, significantly lower transaction costs,114 and prompted the emergence of entirely new markets, such as security trading and commodity markets115 (using contracts never before imagined). Price dispersion, “the measure of ignorance in the marketplace” had been attacked, driving prices lower and uncompetitive firms from the market.

Exhibit 2.4 Growth in GNP Per Annum

| Years | GNP Growth |

|---|---|

| 1869-78 to 1874-83 | 5.58% |

| 1874-83 to 1879-88 | 4.76% |

| 1879-88 to 1884-93 | 3.68% |

| 1884-93 to 1889-98 | 2.55% |

Source: Livingston (Robert E. Gallman, “Gross National Product in the United States, 1834 - 1909,” Output, Employment, and Productivity in the United States after 1800 (new York, 1966). Tables 2,6 at pp. 9,22

Lower prices, talk of depression everywhere, record number of business concerns going under, no end in sight – and on the other hand – record numbers of new concerns forming, and for the adaptive firm, new markets with growing demand for product. The telegraph revolutionized business news, and then made it possible for entrepreneurs to act on the news and contact distant buyers or sellers. To them, lower prices meant more business and profits. It also was incentive to successful industrial firms to invest in expanding production capacity.116 Taking excess information and transaction costs out of commerce did not necessarily mean unprofitable business. Marginal sales could still mean very profitable sales, for if the fixed costs of operations were already covered, new, marginal, sales need only recover variable costs before contributing to the absolute dollars of profits.

Businessman acted. The number of industrial firms, those classified as factories, were the same in 1869 as 1879 – 252,000 to 253,000 – but the value of product sold increased by 59% to $5.4 billion, up from $3.4 billion. Taking into account deflation of 16%, unit output grew even faster than dollar growth. (See Exhibit 2.5 Manufactures: Summary, 1849 to 1923) Industrial concerns – increasingly operating as corporations – were getting both larger, in scale and scope,117 and becoming more efficient producers.

Efficiency, or productivity, became essential when declining prices finally began affecting profits. Fortunately, a new source of energy, steam, was becoming more widely used. In the 1870’s, steam became more important than water power for industrial production.118 Steam enabled a gigantic – discontinuous – improvement in the productive layout and location of factories. For those willing to take the business and capital risks of upgrading to steam, the potential rewards were unprecedented. Not until after the turn of the century did steam power give way to electricity. (Electricity first found use in factories as electric lighting,119 and not until the 1920’s would it become the dominant source of power used in manufacturing.)

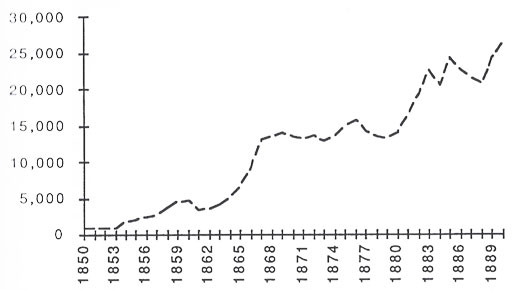

As factories were designed to leverage the use of steam energy, they could also upgrade to the latest new capital equipment, the assets needed to competitively produce product.120 And new technologies began to affect the productivity potential of capital equipment in the mid-to-late 1870’s, and were ubiquitous in the 1880’s.121 Where did all the innovation come from? As soon as the Civil War was over, the annual number of patents awarded took a step function increase from roughly 6,000 to 20,000 patents awarded a year. (See Exhibit 2.6 Patents 1850-1890) A large number of socio-cultural influences caused inventive activity, including two decades of experience developing “American manufacturing,” building and improving railroads and the telegraph, and government spending during the Civil War.122 The needed executives to manage these expansions and new activities were just then becoming available, owing much to the experience gained building and managing the railroads.

Exhibit 2.5 Manufactures: Summary, 1849 to 1923

| Year | Establishments | Wage earners (average) | Primary horse-power | Capital | Wages | Cost of materials | Value of products | Value added by manufacture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factories and hand and neighborhood industries | ||||||||

| 1849 | 123,025 | 957,059 | -2 | 533 | 237 | 555 | 1,019 | 464 |

| 1859 | 140,433 | 1,311,246 | -2 | 1,001 | 379 | 1,032 | 1,886 | 854 |

| 1869 | 252,148 | 2,053,996 | 2,346 | 1,695 | 620 | 1,991 | 3,386 | 1,395 |

| 1879 | 253,852 | 2,732,595 | 3,411 | 2,790 | 948 | 3,397 | 5,370 | 1,973 |

| 1889 | 355,405 | 4,251,535 | 5,939 | 6,525 | 1,891 | 5,162 | 9,372 | 4,210 |

| 1899 | 512,191 | 5,306,143 | 10,098 | 9,814 | 2,321 | 7,344 | 13,000 | 5,657 |

| Factories, excluding hand and neighborhood industries and establishments with products valued at less than $500 | ||||||||

| 1899 | 207,514 | 4,712,763 | -3 | 8,975 | 2,008 | 6,576 | 11,407 | 4,831 |

| 1904 | 216,180 | 5,468,383 | 13,488 | 12,676 | 2,610 | 8,500 | 14,794 | 6,294 |

| 1909 | 268,491 | 6,615,046 | 18,675 | 18,428 | 3,427 | 12,143 | 20,672 | 8,529 |

| 1914 | 275,791 | 7,036,247 | 22,437 | 22,791 | 4,078 | 14,368 | 24,246 | 9,878 |

| 1919 | 290,105 | 9,096,372 | 29,505 | 44,467 | 10,533 | 37,376 | 62,418 | 25,042 |

| Factories, excluding establishments with products valued at less than $5000 | ||||||||

| 1914 | 117,110 | 6,896,190 | NA | NA | NA | 14,278 | 23,988 | 9,710 |

| 1919 | 214,383 | 9,000,059 | NA | NA | NA | 37,233 | 62,042 | 24,809 |

| 1921 | 196,267 | 6,946,570 | -2 | -2 | 88,202 | 25,321 | 43,653 | 18,332 |

| 1923 | 196,309 | 8,778,156 | 33,094 | -2 | 11,009 | 34,706 | 60,556 | 25,850 |

Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1925 (Washington, D. C.: Government Printing Office, 1926)

The rewards of financial success awaited those organizations expanding productive capacity. Successful business concerns acted, and grew in scale and scope. But to do so meant doing business interstate, and having employees and other representatives in other states – two acts, among many, highly constrained by the existing institutions of competitive capitalism. Firm growth also meant new, increased capital investment. During the 1870’s, the period including the longest depression in history, capital investment in factories increased $1.1 billion, up 65%. In the 1880’s, capital investment increased another $3.7 billion, up 134%. Where and how was this new capital raised if the capital markets of the 1880’s did not make it possible?

This then was the crisis: growing markets and technological advances rewarded industrial expansion and the growth of large corporations. Yet expansion also brought corporations into direct conflict with state laws meant to prevent interstate commerce. Nor did the capital markets exist to finance corporate growth. These constraints would be resolved in the next stage of capitalism, corporate capitalism.

Exhibit 2.6 Patents 1850-1890

- [106]:

Freidman and …..p. 77-78; Bordo and Schwartz, Gold, p. 472

- [107]:

Business Annals 1926, p. 131

- [108]:

Freidman p. 87 Contributing to the disturbance was the uncertainty of if, and when, the United States would return to the gold standard – finally decided in 1875 with the passage of the Resumption Act to be effective January 1, 1879.

- [109]:

The estimated total costs of the war is $8.165 billion of which $5.342 billion represents Federal expenditures, $.5 billion the Northern states, and $2.0 billion the Confederate states. Source: David Wells, “The Recent Financial, Industrial, and Commercial Experiences of the United States,” Golden Club Essays, 1872

- [110]:

“One curious result of the war which deserves to be noted, was the very great stimulus which was given to the invention and use of labour-saving machinery; as is shown, first by the increase in the number of patents granted – 3,340 in 1861, and 6,220 in 1865 – and in the further fact, that, notwithstanding the withdrawal, directly or indirectly, during the years 1863-4 and 1864-5 of not less than a million and a half of able-bodied men from productive employments in the loyal States alone, and in great part from the business of agriculture, the yearly products of the soil, and of many other industries, increased rather than diminished.”

- [111]:

Mike, SA …gross natl prod and debt increase - two tables

- [112]:

DuBoff TBD

- [113]:

If the average telegram consisted of 20 words of 8 characters each, then 25 million telegrams would generate 4 gigabytes of data, an amount found on many personal computers in 1996. Four gigabytes was the total electronic messaging sent in the year 1879 within the United States –no wonder we experience an information revolution. And four gigabytes then was radically transforming.

- [114]:

See DuBoff for a much more thorough exposition.

- [115]:

And also giving gise to new markets and institutions such as the Chicago Board of Trade in 1848.

- [116]:

“The obvious explanation for the apparent contradiction is the behavior of prices, which unquestionably fell sharply from 1877 to early 1879, and the continuing state of monetary uncertainty up to the successful achievment of resumption.The contraction was long and it was severe – of that there is no doubt.But the sharp decline in financial magnitudes, so much more obvious and so much better documented than the behavior of a host of poorly measured physical magnitudes, may well have led contemporary observers and later students to overestimate the severity of the contraction and perhaps even its length.Observers of the business scene then, no less than their modern descendants, took it for granted that sharply declining prices were incompatible with sharply rising output.The period deserves much more study than it has received precisely because it seems to run sharply counter to such strongly held views.”

- [117]:

Chandler

- [118]:

Nye p. 194

- [119]:

David E. Nye, “Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology,” p.186

- [120]:

This dynamic of successful factory operations upgrading to steam power, newer technologies, and then electricity – and as appropriate, internal combustion – rode a productivity advance, that if coupled to the right products, was an almost sure path to success. As a consequence, even though the overall period is one of deflation and frequent depressions, it was also one of increasing output, and growing profitability .

- [121]:

“This is not surprising because many of the technological innovations that allowed for the initial development of large firms in these industries appeared during the 1870s and 1880s. To repeat a rather familiar roll call:during the 1870s and 1880s the roller mill was introduced in the processing of oatmeal and flour, refrigerated cars in meat packing, the pneumatic malting process and temperature-controlled tank car in brewing, and food preparation and can-sealing machinery allowed for the mass production of canned meat, vegetables, fish, and soups.During the 1880s, the chemical industry saw the introduction first of the Solvay and then the electrolytic processees in the production of alkalis, and the discovery of the process of producing acetic acid and acetates as byproducts of charcoal production.In the petroleum industry, John Merril’s development of the seamless wrought-iron or steel-bottomed still allowed for a sharp increase in plant size between 1867 and 1873. The 1870s saw the development of the long-distance crude oil pipeline and the steel tank car.In the 1870s and 1880s the Bessemer and open-hearth processes were widely adopted in steel making.In the mid-1880s, new developments in electro-metallurgy made commercial mass production ofaluminum possible.During the same period, a large number of mechanical and chemical innovations were devised that greatly facilitated the process of refining and working various metals.The development, beginning in 1880, of improved metal-working machinery based on the use of high-speed-tool steel allowed for the production of a wide variety of better machines with finer tolerances.The typewriter, invented in the late 1870s, was mass produced during the 1880s.The electrical street railway car came into widespread use during the late 1880s.In addition, of course, the basic transcontinental railroad and national telegraph networks – infrastructure necessary for the rise of firms capable of distributing products on a national basis – were complete by 1880.”

- [122]:

Quantify TBD