Chapter 14 - Internetworking: Emergence 1985-1988

14.21 cisco Systems

Leonard Bosack and his wife, Sandy Lerner, started cisco Systems for very different reasons than those motivating Paul Severino and his team. They didn’t have to spend years finding the seed of a great idea, one around which to create a fast-growing company to take public and holding the potential to support a large, successful enterprise. No, they had little calling to become entrepreneurs or earn entrepreneurial profits. In fact, if anything, they were happy academics willing to give what they had or knew away, resistant to even marking-up their production costs to make a profit. So when Stanford University said they could not build product on university property and sell it to commercial companies, they felt they had little choice and left Stanford and started a journey that most entrepreneurs can only dream of and few ever have the opportunity to realize: a company worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

Bosack and Lerner met in 1977 while sharing time on Stanford University’s minicomputers.91 Lerner was a graduate student and Bosack fit the description of a “computer nerd.” They fell in love, married, and took jobs with the Business School’s and Computer Science computer departments, respectively. As such, they became involved in a number of efforts by Stanford to create a unified campus network. Stanford had thousands of different computers and users wanted to share information across the computers as if there was really only one integrated system. To do so, the computers, with their different operating systems and communication protocols, had to be able to easily inter-exchange information. After a number of failed efforts, by June 1980, Bill Yeager, an engineer with the Medical School, had created a working router.92 Even so, it still did not connect to the Ethernet network that was integral to the Stanford University Network (SUN). Frustrated, in 1982, Bosack, Lerner and other engineers worked without authorization to create both an interface between Yeager’s router and Ethernet and then to pull the coaxial cable needed to connect the computers throughout the campus. Yeager joined their efforts as did other engineers and before long their “skunk works” project was a success. To build additional routers, Bosack and Lerner converted their living room into an assembly room. Routers were then tested on the SUN network and the IMP’s that connected to the Arpanet. Word of the routers spread both within Stanford and through the crude email of the day to other research centers and universities. Swamped with orders and needing a way to satisfy demand, other than by using their living room and credit cards, they approached Stanford and the Office of Technology Licensing (OTL). Only OTL could not offer a solution that would take less than years. Again frustrated, they left Stanford to start a business that would become cisco Systems.93

On December 10, 1984, Bosack and Lerner incorporated cisco Systems. Little changed other than that they could now take orders from any organization. As the order flow increased, the living room got more and more crowded and the need for cash more pressing. In the roughly eight months to July 31, 1985, sales totaled $109 thousand. The lack of cash and, therefore, the need for investment capital to grow an organization and develop the market forced Bosack and Lerner to mortgage their home to the max, borrow as much as they could on their credit cards and from friends. Strapped for cash to pay their bills, Lerner took a daytime job managing the research computing systems for Schlumberger Computer Aided Systems Laboratory.

The constraint of cash had two other effects on the early history of cisco Systems. First, unable to invest in a direct sales organization, the company had to resort to using manufacturer’s representatives who were only paid when sales were made. This limited sales to customers that did not need a lot of technical support, organizations such as universities, research laboratories and government agencies, especially the government. These early adopters were also the easiest to reach through their Stanford connections and email networks. The second effect was the liberal use of part-time and contract engineers to develop products, primarily software products that executed on a small number of generic hardware platforms.

Revenues for the twelve months ending July 31, 1986 were essentially flat year over year: $129 thousand. Bosack and Lerner realized that if they wanted to be successful, they need capital and professional help. So they, like so many entrepreneurs before them, began the search for venture capital.

Finding venture capital proved a lot more challenging than Bosack and Lerner had imagined it would be. Bosack recalls:

We must have talked to 80 to 90 different venture firms. We got turned down by just about every one.94

It quickly became apparent that without serious management, the probability of raising capital at an acceptable valuation was remote. So in January 1987, they hired a President and Chief Executive Officer, William Graves, and then a vice-president, finance in March.

Fortunately one of the venture capital firms they did talk to was Sequoia Capital, one of the most successful and largest venture capital firms in Silicon Valley. A dominant firm, Sequoia Capital had the resources not just to evaluate investment projects they received or discovered, but to do the research and thinking required to become strategic investor – to look for investments they wanted to make. When they listened to Bosack and Lerner, the partners of Sequoia heard not a company needing capital but a raw start-up needing everything, everything that is other than an intriguing jump on a product idea they had identified in their partners’ meetings as compelling. Bosack and Lerner felt mentally stripped but not rejected: they realized the partners, and especially the managing partner, Don Valentine, weren’t questioning the product viability, only their ability to build a company fast enough to compete with much larger, entrenched competition. They left agreeing to provide the information, and time, so that Sequoia Capital’s partners could do their due diligence. They also knew that if they got an offer from Sequoia Capital, they would take it.

The fact that sales for fiscal year ending July 31, 1987 were $1.5 million, with nearly a 10% net income before taxes, kept cash usage to a minimum and enabled the company to continue to grow modestly while they sought venture capital.

Valentine soon proposed that Sequoia Capital invest $2.5 million for 32 percent of the company. Bosack and Lerner would retain 30 percent of the company, ownership that would vest over four years. Valentine would become a member of the Board of Directors and, much to the relief of the founders who recognized that they had no interest in the management aspects of the company, would assume responsibility for finance, and help Graves build a management team, sales organization and “operations process.”95 Bosack became chief technology officer and Lerner vice-president of customer services. The financing closed in December 1987.

In early 1988, during an interview for an article to be published in Electronics magazine, Graves made a number of telling comments.96 First he referred to cisco System’s products gateways, not routers, and terminal servers. Second, he stated that their gateway technology could “ handle networks as large as 100,000 subnets in an integrated WAN comprised of multi-media, multi-protocol and multi-vendor subsystems. At this time his claims were largely marketing hyperbole, but in the future Cisco and others would make the products to prove his claims prophetic.

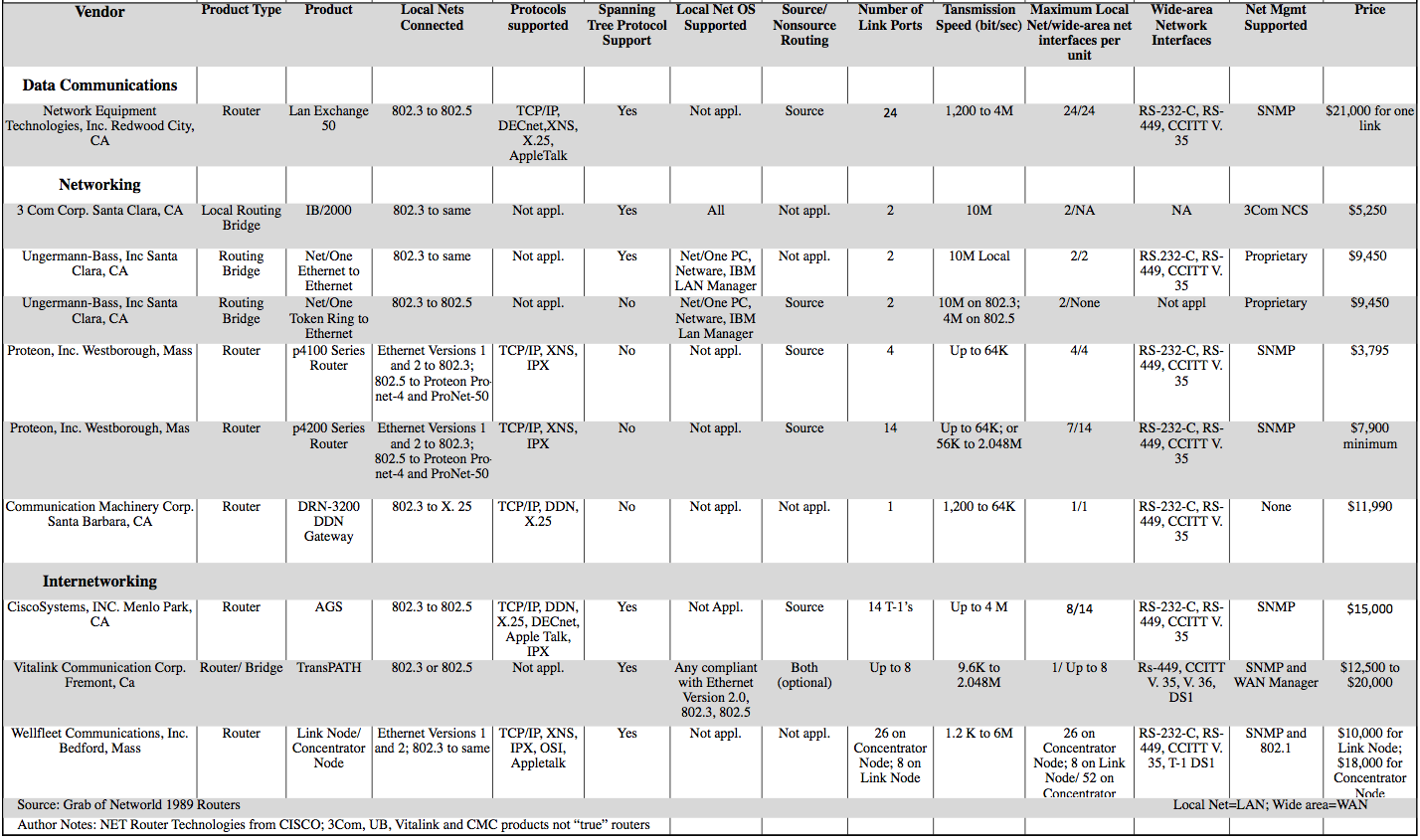

Don Valentine, and a fellow senior partner, Pierre Lamond, began devoting the kind of time to cisco Systems that few companies receive. It became obvious to them that a stronger management team was needed and, in May 1988, President Graves, was replaced with an interim President until an executive search could identify a candidate acceptable to Sequoia Capital. (See Exhibit 12.15 1989 Router Vendors)

Fortunately, the $2.5 million investment cisco Systems raised proved to be sufficient as eager customers placed orders on attractive terms and the lack of competition allowed the company to essentially build product once orders were received. The combination kept the growth in working capital (accounts receivable plus inventory less accounts payable) to a minimum. Thus, cisco grew by more than a factor of three for the fiscal year ending July 1988 without having to sell more stock. The sales for fiscal year 1988 totaled $5.5 million with net income before taxes and interest of $555 thousand.

In October 1988, John Morgridge became the new President and CEO. He would prove to be a superb hire as was management team soon recruited. In December 1988, Valentine became Chairman of the Board of Directors. All was going as hoped and planned other than growing contention with the founders.

Although cisco Systems was a small organization compared to those Morgridge had managed, his due diligence had accurately revealed that the company’s products were superb, maybe the best currently available and, given the market prospects, he truly joined a large company while it was still small. Even so, he could not have hoped for the outcomes awaiting him.

Exhibit 14.21.1 1989 Router Vendors

- [91]:

David Bunnell and Adam Brate, Making the Cisco Connection, Wiley&Sons, Inc., 2000, p. 2

- [92]:

Ibid., p.5

- [93]:

Ibid., pgs. 2-7 This reconstruction borrows liberally from this book.

- [94]:

Eric Nee, “cisco and Wellfleet in a Rout,” Upside Magazine, Feb./Mar. 1991, p. 43

- [95]:

Bunnell and Brate, “Making the Cisco Connection,” p. 10-12

- [96]:

“Inside Technology,” Electronics, April 14, 1988, p. 74