Chapter 4 - Networking: Vision and Packet Switching 1959 - 1968

4.4 Paul Baran - 1959-1965

Paul Baran exemplifies the principal that if one must work, find something really important to work on. Ever exuding a quiet, even polite, intensity that speaks of someone who is confident of what he is thinking, by 1959, just ten years out of college, Baran already had discovered the problem he wanted to work on. Baran wanted to prevent a nuclear holocaust, not for money or fame, but from personal angst. After graduating from Drexel Institute of Technology, he went to work for the computer start-up Eckert-Mauchly Computer Company before moving on to Raymond Rosen Engineering Products. A few years later, he moved to California and landed a job with Hughes Aircraft as a junior engineer on the Minuteman missile control system. These experiences proved important training in digital design and implementation. While at Hughes, he attended UCLA graduate school at night where he earned his master’s degree in engineering. Baran then joined RAND where he dedicated himself to solving the problem of nuclear missile command and control. At the time, he had absolutely no concept of a solution or that his solution one day would be seminal to a global communications revolution destined to transform human society.

RAND, short for “research and development, “is a unique organization. Created at the end of World War II to preserve the operations research capability developed by the Air Force during the war, it first found home tucked under the protective wing of Douglas Aircraft Corporation in California However, a research organization managed by a manufacturing organization proved an uncomfortable fit. To secure its autonomy, the Ford Foundation advanced seed money to convert RAND into an independent, non-profit research organization chartered to work on problems of national security. Being a true think tank, it never implemented ideas developed by its staff, but left them for other organizations to pursue. An exception came early, when MIT Lincoln Labs subcontracted computer programming for the SAGE project to RAND. In two short years, RAND would divest the effort to a specially created organization funded by the Air Force: Systems Development Corporation, better know as SDC.

One way the Air Force made RAND researchers aware of its needs was to distribute a weekly list of requests for study.6 Baran, in search of a project, reviewed the weekly postings and his interest was soon sparked by a project concerning the survivability of the military’s strategic command and control system. Baran made a proposal, which was accepted, and he began by studying the survivability of the AT&T telephone network – the communication system the Air Force depended on. He concluded it was a disaster: a few well-placed bombs could disrupt communications throughout the country.

Baran had found his focus:

How to build a robust communications network that could survive an attack and allow the remainder of the network to behave as a single coordinated entity?

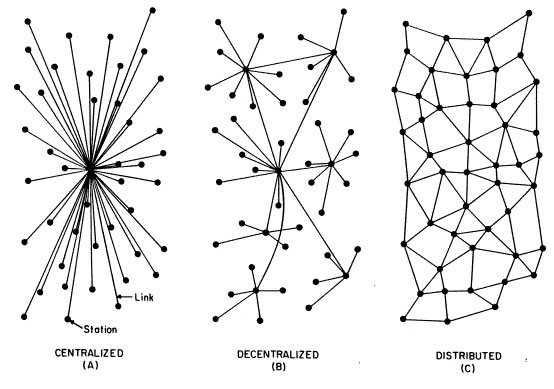

AT&T’s telephone network vulnerability came from its highly centralized design. At the time, networks were either centralized or decentralized. In centralized networks, all end points (nodes) connect to one central switching point. In decentralized networks, clusters of smaller centralized networks are interconnected to form one large network, thus eliminating a single point of system failure. (See Exhibit 2.0 Centralized and Decentralized Networks.)

Baran then looked to see if more robust networks could be constructed than decentralized ones. In his investigations, he was strongly influenced by his understanding of how the brain worked. He had numerous interactions with Warren McCullough of MIT, an influential cognitive scientist. Inspired, Baran examined networks in which every node connected to every other node – a distributed network, but found little if any research on the subject. (See Exhibit 4.1 Distributed Network.) To discover how distributed networks behaved under disruptions, Baran modeled various configurations and simulated attacks against the network. He concluded:

A critical mass of the structure occurred when a network reached about 15 to 20 nodes in width and used a redundancy level of about three times as many links as the minimum needed to tie all the nodes together.

Exhibit 4.4.0 Centralized, Decentralized & Distributed Networks

As to how to build such a network, Baran recalls:

Having figured out how to get robustness, I then had to tackle the problem of getting signals through this fishnet type of network. Analog signals deteriorate rapidly when you have many links in tandem. Therefore, I concluded that all communications would have to be digital to maintain signal quality. I initially thought in terms of ‘minimal essential communications.’ I proposed to relay teletype signals from one AM broadcast station to another, building on an idea earlier proposed by Frank Collbohm, the President of RAND Corporation. (Unlike skywave HF transmissions, AM broadcast ground wave signals did not depend on the ionosphere for propagation.) The limitation of Colbohm’s idea was that there was no intelligence to relay signals. I proposed merely to flood the network where subsequent messages wash out the older messages.

Baran presented his solution to the Air Force. He was told that while his proposal might take care of the President, the Air Force and other military branches also needed a system with a lot more capacity to communicate with field personnel.

In November 1962, Baran presented a paper titled: On Distributed Communications Networks.7 In it, he proposed the radical computer communication concept of standard message blocks routed as “hot potatoes” in a store-and-forward system. He would write:

In communications, as in transportation, it is most economic for many users to share a common resource rather than each to build his own system, particularly when supplying intermittent or occasional service. This intermittency of service is highly characteristic of digital communication requirements. Therefore, we would like to consider one day the interconnection, of many all- digital links to provide a resource optimized for the handling of data of many potential intermittent users: a new common-user system. Present common carrier communications networks, used for digital transmission, use links and concepts originally designed for another purpose - voice. These systems are built around a frequency division multiplexing link-to-link interface standard. The standard between links is that of data rate. Time division multiplexing appears so natural to data transmission that we might wish to consider an alternative approach, a standardized message block as a network interface standard. While a standardized message block is common in many computer-communications applications, no serious attempt has ever been made to use it as a universal standard.8

As to how the messages will be passed, Baran creatively proposed:

Torn-tape telegraph repeater stations and our mail system provide examples of conventional store-and-forward switching systems. In these systems, messages are relayed from station to station and stacked until the “best” outgoing link is free. The key feature of store-and-forward transmission is that it allows a high line occupancy factor by storing so many messages at each node that there is a backlog of traffic awaiting transmission. But the price for link efficiency is the price paid in storage capacity and time delay. However, it was found that most of the advantages of store-and-forward switching could be obtained with extremely little storage at the nodes. Thus, in the system to be described, each node will attempt to get rid of its messages by choosing alternate routes if its preferred route is busy or destroyed. Each message is regarded as a “hot potato,” and rather than hold the hot potato, the node tosses the message to its neighbor who will now try to get rid of the message.9

Baran began presenting his ideas to others. He remembers:

I conducted probably 40 or more briefings around the country on my research throughout government and to major research organizations. Many who were proficient in computer technology felt the concepts to be viable. Those who were familiar only with conventional analog transmission had the most difficulty. AT&T that held the monopoly for telecommunications at the time was among the most negative.

Baran submitted his seminal paper to the “IEEE Transactions on Communications Systems” in October 1963 and it was published in March 1964. In August 1964, RAND Corporation published “On Distributed Communications,” Vols. I through XI by Baran with Sharla Boehm co-authoring Volume II and J. W. Smith authoring Volume III. These volumes set forth the concepts of how communication networks could be designed as a message-based, distributed system.

Yet it remained only an idea. To really see if it worked, a message-based system needed to be built. In 1965, the opportunity seemed to present itself. Baran remembers:

In 1965, a formal RAND Recommendation was made to the Air Force to implement my plan. The Air Force had the not-for-profit MITRE Corporation organize a committee to review the subject in detail. The recommendation of the committee was to immediately proceed. Then came one of those brilliant strokes of higher-level management. The Department of Defense ruled that the agency that should be building the system was the Defense Communications Agency, not the Air Force, since it would be used by more than one service.

Given the composition of the Defense Communications Agency (DCA) – personnel with no computer or digital experience, exactly those who had proved most skeptical and negative to these new ideas – Baran recommended the project be shelved, arguing it was better to wait for the right group to manage its creation.

- [6]:

Baran remembers RAND as “a neat place: It was multi-disciplinary, and the reason its output was as productive as it was, it had the neatest way of allowing people to do pretty much what they wanted to do. They picked very good people to start with, were able to pick those they wanted, and they guaranteed them continuity and no interference, and then they’d restrict the output flow, so any briefing had to go through a tough review process. Before anything became a RAND report, it went through a very, very careful review process, so all the failures, all the nonsense got filtered out, and as a result, you know, my God, you got some very high quality output. So it was the ability to bury bad work easily that I think made for a lot of success. RAND, at the time, was funded by the Air Force, and the Air Force was synonymous with the national defense, ‘cause what the hell was national defense, then. You had airplanes and they carry a bomb and that was national defense.”

- [7]:

The paper was presented at the First Congress of the Information Systems Sciences, sponsored by MITRE.

- [8]:

Baran, On Distributed Communications Networks

- [9]:

Baran, On Distributed Communications Networks