Chapter 5 - Data Communications: Market Competition 1969-1972

5.8 AT&T and Computer Inquiry I 1970-1971

After the FCC had issued the Report and Further Notice of Inquiry to solicit opinions on the SRI study and while waiting for the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) report regarding the DAAs, Strassburg remembers his perspective changing:

We, I at least, felt there was a compelling reason to be concerned about certain trends that were out there, that Bell couldn’t be all things to all people for all times, that the environment had changed, or was changing, and that innovation and creativity didn’t all start within the walls of Bell Labs, and all the wisdom wasn’t necessarily in Bell Labs. We were also concerned – I was concerned that AT&T was beginning to grow big, in terms of not only revenue – they had always been dominant as a corporate power – but at this time it was getting awfully big, so was there room for other participants in this marketplace called communications?”

On April 3, 1970, the FCC issued its Tentative Decision and Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 28 F.C.C. 2d 291 (1970) or the “Tentative Decision.” The entire proceedings become popularly known as the “Computer Inquiry.”25 Public argument on the Tentative Decision was scheduled for September 3, 1970, and March 18, 1971.

The Tentative Decision addressed four key issues:26

Data Processing Computer Services

Everyone agreed that data processing did not exhibit economies of scale as did natural monopolies such as telephone exchange services. Therefore, the FCC concluded:

…in view of all the foregoing evidence of an effective competitive situation, we see no need to assert regulatory authority over data processing facilities in order to link the terminals of subscribers to centralized computers.27

The Commission retained the prerogative to “re-examine the policies set forth herein…if there should develop significant changes in the structure of the data processing industry.”

Common-Carrier Provision of Data-Processing Services

The issue of common carriers offering data processing services was a more complicated issue and one that remained unresolved until the Final Report. The problem arose because data processing had been declared an unregulated activity. How could economically motivated cross-subsidies within common carriers from regulated to unregulated businesses be avoided?

Store-and-Forward Message-Switching Services

The FCC concluded that message-switching services are “essentially communications” and “warrant appropriate regulatory treatment as common carrier services under the Act.”28

Hybrid Services

Hybrid services were those having both data processing and message-switching components. The Commission, using a “primary business test,” declared that:

Where message switching is offered as an integral part of, and as an incidental feature of, a package offering that is primarily data processing, there will be total regulatory forbearance with respect to the entire service whether offered by a common carrier or non-common carrier, except to the extent that common carriers offering such a hybrid service will do so through [separate] affiliates…..If, on the other hand, the package offering is oriented essentially to satisfy the communications or message switching requirements of the subscriber, and the data processing feature or function is an integral part of, and incidental to message switching, the entire service will be treated as a communications service for hire, whether offered by a common carrier or a non-common carrier and will be subject to regulation under the Communications Act.29

In September, the FCC heard oral arguments on the Tentative Decision from some twenty interested parties.

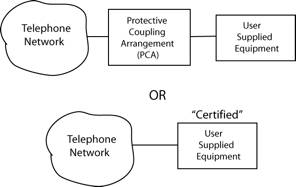

In June, 1970, the FCC received the NAS report commissioned in response to the uproar by the independent modem manufacturers over the tariffs filed by AT&T requiring the use of PCAs (DAAs).30 (See Exhibit 5.8.1 - NAS Recommendation.)

The report concluded:

- Uncontrolled interconnection could cause harm to personnel, network performance, and property.

- The use of protective couplers and signal-level criteria was an acceptable way of assuring network protection; however, the added equipment increased overall costs.

- A program of standards and enforced certification of equipment would be another acceptable way of assuring network protection.

In a subsequent study commissioned by the FCC, Dittberner Associates, a Washington-based firm of computer consultants, concluded that manufacturers of data modems and other types of interconnected customer equipment could easily build into their equipment the necessary circuitry to protect the telephone network. The common carriers need not be the only ones providing network protective couplers.31 Furthermore, a program of standards and certification would be an inexpensive way to extend interconnection privileges without harm to the common-carrier network.

Both the NAS and Dittberner reports agreed that safe attachment of customer provided equipment could be accomplished without the objectionable carrier-supplied access arrangements or PCAs.32 Knowing an alternative to the PCAs existed, and given no cessation of complaints – long delays in getting PCAs installed, too expensive, and constantly changing interface specifications – the CCB needed a plan of action. Due to manufacturer and customer interest, PBX standards and certification procedures were attended to first. On March 26, 1971, the FCC established a PBX industry advisory committee with some thirty members representing carriers, equipment manufacturers, and users. This committee had the responsibility of devising technical standards, as well as creating certification and enforcement procedures permitting direct connection of PBX equipment to the telephone network – without using PCAs.33

In that same month, on March 18, 1971, the FCC, in a divided 4 to 3 vote, rendered its Final Decision in the Inquiry (Final Decision, 28 FCC 2d 267 (1971)).34 In it, the FCC introduced the concept of “maximum separation” to solve the problem of common carriers wanting to provide data processing services.35 To compete in the unregulated field of data processing services, common carriers must create separate subsidiaries with separate books of account, separate officers, separate operating personnel, separate equipment, and facilities devoted exclusively to the rendition of data processing services.36 These subsidiaries would lease communication services from carriers (the parent company or any other carrier) under public tariffs, just like competing suppliers of data-processing services.37 Some issues remained, however, particularly those of “hybrid services.” But in general, the regulatory issues between data processing and communications seemed to have been settled.

Exhibit 5.8.1 - NAS Recommendation

- [25]:

Only years later, when additional Inquiries are held, will this Inquiry be referred to as Computer Inquiry I.

- [26]:

This text is either direct or indirect citation from: “Regulatory and Economic Issues in Computer Communications,” IEEE vol. 60, pp 1257-1261 November 1972.

- [27]:

28 FCC 2nd 291 (1970), at 298

- [28]:

62 “One example of a message-switching service which, if offered on a commercial basis to the public at large would, under the Commission’s present rules, have to operate as a common carrier, is the computer network of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA).” See Chapter 5 for the history of the ARPA network.

- [29]:

28 FCC 2nd 291 (1970), at 305

- [30]:

National Academy of Sciences, Computer Science and Engineering Board, A Technical Analysis of the Common Carrier/User Interconnections Area, Rep. to the FCC, June 1970

- [31]:

Dittberner Associates, Interconnection Action Recommendations, Rep. to the FCC, Sept. 1970

- [32]:

“Regulatory and Economic Issues in Computer Communications,” IEEE vol. 60, pp 1257-1261 November 1972.

- [33]:

Ibid

- [34]:

Common Carrier pg. 191

- [35]:

Computer Law Service, “The Computer Inquiry-The Regulatory Results,” Bernard Strassburg, Callaghan & CO, 1973, pgs 2-3: “Thus, the commission invoked the doctrine of ‘maximum separation’ by which to insure that the regulated activities of the carrier are in no way commingled with any of its non regulated activities involving data processing… Essentially, the degree of separation required by the commission was premised on the following regulatory concerns: (1) that the sale of data processing services by carriers should not adversely affect the provision of efficient and economic common carrier services; (2) that the costs related to the furnishing of such data processing services should not be passed on, directly or indirectly, to the users of common carrier services; (3) that revenues derived from common carrier services should not be used to subsidize any data processing services; (4) that the furnishing of such data processing services by carriers should not inhibit free and fair competition between communication common carriers and data processing companies or otherwise involve practices contrary to the policies and prohibitions of the antitrust laws.”

- [36]:

28 FCC 2nd 267, at 270

- [37]:

“Regulatory and Economic Issues in Computer Communications,” IEEE vol. 60, pp 1257-1261 November 1972.