Chapter 2 - Background

2.0 Terminology

Computers represent the defining technologies of the Information Economy. By the turn of the century, life in modern society are unimaginable without the aid of computers, and yet in the early 1950’s, few people could imagine how more than a handful would ever be needed. To understand the emergence and dynamics of computer communications first requires an understanding of how computers evolved from 400 ton cabinets, or entire rooms full of tube racks, to desktop personal computers. For the explosive growth in the use of computers drove the need for computer communications.

When the first electronic computer was powered up in late 1945, (or potentially the Colossus computer of 1939-1940) it was not because those involved saw a bright economic future for computers. Instead, it was because the military needed machines that could do faster calculations. Those designing ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Calculator) drew on core ideas then almost three hundred years old. Once reduced to practice, the ENIAC computer was quickly surpassed by newer and better versions. Even so, few believed they held value for business, and it was not until 1954 that a computer was sold to an organization other than the government. By the early 1960’s, over one hundred different computers had been designed and built to find the best design. Then in 1963, IBM announced the System/360. It became the “dominant design”,1 and businesses’ accelerating growth in the use of computers launched an explosion in computer revenues. By 1968, revenues exceeded $5 billion; and by 1988, $35 billion.

This chapter will begin with a brief introduction of technology and its relationship to product. These ideas will surface throughout this work, and prove indispensible to understanding the relationships of technology and economic growth. Also to be introduced will be the concept of market-structures. Corporations innovating technologies in competition with each other coalesce into orderly patterns of co-evolution. These patterns will be observed as market-structures. The history of computers will then be reconstructed using these concepts.

Technology & Market Structures

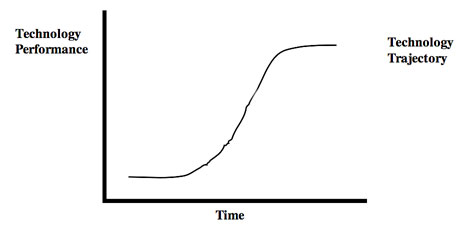

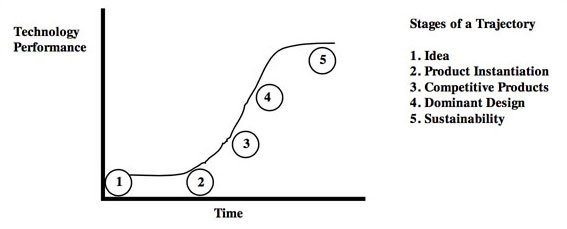

This pattern of growth and change of a technology from an idea, to first product, to dominant design, to rapid growth is not unusual, but the norm. The pattern represents a particular “trajectory.”2 Such a trajectory tracks the changes in a technology’s performance over time; where the definition of performance can vary (See Diagram 1.0 Technology Trajectory). Trajectories can assume virtually any pattern. Successful trajectories, however, generally resemble an “S-curve,”3 and can be thought to represent the cumulative learning curves4 of all firms innovating the technology. In the discussion to follow, trajectory implies a range of possible futures with the S-curve the normative case.

Successful technologies will be thought to progress through five distinct stages. The concept of stages is expository only, and carries no implication of pre-determination. As will become clear, patterns of technological change, and development, are a consequence of many factors, of which the intrinsic “superiority” of the technology is but one factor, often not the most important one.

The first stage begins with an Idea. Since ideas originate with people, a person, or persons, initiates each technology and thus trajectory; for the technologies of interest herein, the people are invariably members of an organizations. Most ideas remain undeveloped, sometimes for centuries. The idea of computers, for example, dates to the 17th century. If an idea holds sufficient potential, incentive may exist to transform the idea into product.

It is product that converts technology into an economic good. Consequently, the first time a product embodying a new technology is created begins the second stage of a technology trajectory. This stage will be called Product Instantiation (See Diagram 1.1 Stages of a Technology Trajectory). Almost without fail, an organization, or organizations, will be involved. In the case of computers it was the University of Pennsylvania. Organizations are the economic entities that invest the capital needed to finance all the tasks necessary to transform idea into product. Investment is key. Investment need not be motivated by financial gain — U.S. Government investment advancing computing technologies during World War II, for example, was motivated by national security. Regardless of the reason, investment, risk capital, funds the transformation of idea into product by organizations.

Once a product exists it must then stand the test of value. If valuable, and if the technologies hold the potential to be improved, then there may be justification – investment logic – to create another, improved version of the product. The newer product benefits from what was learned during prior creation as well as use. The second computer, EDVAC (Electronic Discrete Variable Automatic Calculator), differed from ENIAC in that it did not have to be rewired for every new use but used encoded instructions – a significant improvement, and one central to the advancement of computing.

If a technology, and its embodiment as product, beomes recognized as economically attractive, other organizations will begin innovating5 it. Initially, each organization will pursue unique innovation strategies to gain competitive advantage – innovating in ways they believe best responds to market demand. Once multiple organizations begin innovating products in competition with each other, their combined actions drive the technology trajectory into a new stage, to be called Competitive Products .

Firms will continue to pursue their own strategies of exploration and exploitation6 until a dominant design has emerged. In exploring, each firm continues to search for the most competitive product, whereas once it believes it has found such a product, it attempts to exploit that product optimally. When the dominant design emerges, those products not conforming to it, begin to fade in importance. Those firms that can, switch their innovation strategy to be in concert with the dominant design. How one product, or design, achieves dominance is highly “path dependent,” with being best, however defined, just one factor.7 Users buying the product – to be labeled broadly as “buying demand” – are the ultimate test. The coming into being of a dominant design signifies that the technology trajectory has evolved from the Competitive Product to the Dominant Design stage. Once the dominant design has emerged, successful firms will produce increasingly interchangeable product, although firms can add differentiation in many other ways. Much more will be said about dominant designs in future chapters.

If the dominant design is robust, that is it can adapt to future requirements without destroying the competencies of the successful firms, then the trajectory might last for a long time, and become sustainable. Sustainability is the last stage of a technology trajectory. Finding technologies that lead to sustainable products while generating meaningful economic growth is essential to both firms and economies.

Product, the economic good or artifact, and the object of economic exchange, can be conceptualized as a “black box.”8 First, imagine a black box – you can see what it looks like but you can’t know what is inside it. As a consequence, you haven’t any idea what to use it for. Once instructed in its use, you are then faced with a choice. You can either decide to change your behavior and make use of the black box, or not. You hold the perspective of the user. Economically, a most important condition is financial gain from using the product.

In the early 1950’s, using computers to calculate solutions to complicated and complex problems was thought to take “forever.” The military, however, needed computers fast enough to make possible an air defense system as protection against and deterrent to the Russians. They wanted computers to perform in “real-time.” They were concerned with use, others had to design and manufacture the computers.

Those others view the black box from the inside. They hold the perspective of the designers and builders. For them, the world is much more complicated. They must care how it is used, for if it is not used, it will not be successful, and if it is not successful there is no reason to make it. (To the individuals that means no income, i.e. job; to the firm, no profits, no cash, no existence.) Designers and builders must also master what is necessary to design and create the product.

In creating product, designers and builders can change either the product’s “architecture”9 or the “components” with which it is built. The architecture is the product’s design – how the components are assembled to produce function. Different architectures can lead to profoundly different products, so different in fact, that even products using common components function differently. For example, early computers, television sets and radios all shared the common component of the vacuum tube – yet in each product, the vacuum tube served different purposes.

When an architecture becomes sufficiently unique, it defines a new “paradigm.”10 A paradigm includes the knowledge, problems, procedures, tasks11 and experience required to master the architecture. Paradigms will be discussed more fully later.

Once in existence, successful product will justify the innovation of new, improved versions. Designers now have different architecture and component choices. Choice has been created by the passage of time, prior experience, customer requirements, organzation capabilities, funding, availability of new architectures, new components, and so on. Most often, the choices lead to “incremental”12 improvement of the prior product. If significant, product advances can be viewed as leaps, or step-like improvements, measured in generations. Computers, televisions, and radios have all changed over time based on the innovation of successive generations of newer and better versions.

New paradigms often cause a “ technological discontinuity.”13 If so, the new product is not the next generation of a prior product, but a product of entirely new characteristics that make it distinct, or “ radical”14 – the computer from the television set. In the following history of computers, three computer paradigms will emerge: mainframe computers, minicomputers and personal computers

In 1968, the integrated circuit led to incremental innovation in mainframe computers, the IBM System/360 architecture, and concurrently, radical innovation as minicomputers. A decade later, microprocessors led to incremental innovation in minicomputers, and to some extent mainframe computers, and radical innovation as the personal computer. By 1988, the combined revenues of these three computer market-structures soared seven-fold in just twenty years, to $35 billion.

Using these terms, this chapter can be summarized as a story of how computers changed over time in response to three technological discontinuities – those caused by the transistor, integrated circuit and microprocessor. During this same period, users’ requirements, or buying demand, were also changing – from batch processing; to real-time computing; to real-time, on-line computing; and finally to personal distributed computing. These new user requirements, when architected into products using the newest component innovations, gave rise to two new computer paradigms – minicomputers and personal computers. By 1988, these three computer paradigms were co-evolving, and were instantiated as economic entities in firms and economic objects as products.

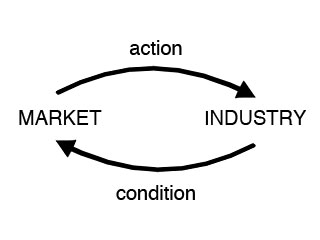

Which raises the last interpretive concept needed for this chapter – “ market-structures. “ Firms that innovate and sell products in competition with each other constitute both markets and industries. Markets and industries are neither synonymous nor do they exist independent of each other. A market is a process, a dynamic, a game of economic exchange enacted by economic agents – in the case of computer communications, by firms. Like all games, markets function according to rules. Some rules are very general, such as those governing private property, contracts, and commerce. Others are market specific, such as regulations and antitrust constraints.

Firms innovate technologies to create economic objects, products, that are exchanged, thus giving rise to markets. The success and failure of all firms’ actions constitute industry structure – the ordering of the economic agents with respect to each other. One form of industry order classifies an industry as a monopoly, oligopoly, or competitive. In a monopoly, order resides as one firm; in an oligopoly, a few firms dominate; and in a competitive industry, all or most firms are capable of influencing market futures.

Market and industry constantly define and refine one another’s existence and potential via the actions of all firms. Market as process and industry as structure with processes acting on structures that condition future processes, and so on. This mutual co-evolution of a market and industry will be called a market-structure.15 (See Diagram 1.2 Market-structure) Market-structures become constructed from the actions of firms, and do not exist a priori, simply waiting for firms to discover them. Equally, firms can be members of many market-structures, in some marekt-structures they are vitally important to collective outcomes, in others they are strictly peripheral.

Market-structures are the firm and product instantiations of technology paradigms. Every paradigm gives rise to a new market-structure. The three computer paradigms central to this history will be observed as three distinct, yet co-evolving market-structures. More will be said about the dynamics of market-structures in future chapters.

Finally, contrasting computers and communications, the telecommunications market-structure in 1968 was a regulated monopoly – only American Telephone & Telegraph (AT&T) could provide telecommunications products and services.16 But by 1988, telecommunications also consisted of multiple market-structures, each of which had unique market processes and industry structures. The transformation of the regulated telecommunications market into a competitive one is told in the next Chapter – Changing Rules of Competition. But first, a history of computing.

Telecommunications

The accelerating use of computers by organizations in the mid-1960’s looked like it might run aground on the restrictive policies and practices of American Telephone & Telegraph (AT&T), the regulated monopoly of telecommunications. In sharp contrast to the turbulent, market-structuring dynamics of computers, where innovation knew no bounds, telecommunications had become ingrown, with AT&T aggressively resisting new uses of the telephone network, even those made possible with products it had innovated. For twenty years, AT&T fought to preserve the institutional arrangements that protected it from the uncertainties of market competition. Then in two landmark rulings by the Federal Communication Commision (FCC), Carterfone (1968) and MCI (1969), competition with AT&T was made possible. By 1983, the war of ideas and technologies had been won, and on January 1, 1984, AT&T, the largest corporation in the world, reorganized into eight new corporations.

The case of AT&T shows that market economies do not just happen, but require intentional action. When the Founding Fathers framed the U.S. Constitution, they intentionally strengthened safeguards for private property, believing private property an innate right of man, and when protected by law, private economic behavior promoting the public good would result. Corporations, however, factored little into their deliberations, both because they lived in an agrarian society, and because corporations were equated with the detested monopolies of Britain. But with time, it became apparent that society needed to incentivize collective actions to accomplish what government was neither authorized to do nor capable of doing. Corporations, therefore, became important to the evolving economy, and so both the national and state governments enacted rules to incentivize their creation and use. Over time other new rules were needed to foster economic behavior, rules enforced by institutions, such as those which would later regulate AT&T.

A brief introduction of institutions will be followed by an overview of the history of the institutions of American capitalism up to the 1870’s. When AT&T was founded in 1873,17 the prevailing industrial conditions were known as competitive capitalism. Industrial firms were small, state constrained, and owner-managed. Not one public industrial corporation existed. Competitive capitalism proved only transitional however. For in 1832, the vision of a entrepreneur gave birth to the telegraph that unleashed the Information Revolution. The story of the subsequent crisis of competitive capitalism and the rise of corporate capitalism will be told next – for by World War I, corporate capitalism had overwhelmed competitive capitalism, and the economy was soon dominated by oligopolies of large public companies. During those revolutionary times, 1880 to 1914, AT&T and telecommunications assumed forms that would last until the assault of computers began in the mid-1960’s. That story will constitute most of this chapter. The focus of the reconstruction beginning in the mid-1960’s will be of how users won the rights to attach and interconnect equipment of their own choice to the telephone system.

Institutions

Institutions,18 like market-structures, order interactions among corporations. The two function very differently however. Market-structures represent order emerging from the interactions of corporations – order that can neither be guaranteed to emerge nor to persist. Institutions, on the other hand, enforce order on corporations by making them conform to rules. Being able to impose rule-based behavior is important, for frequently, economic consequences are thought better decided by reason, or the political process, than left simply to the chance of market dynamics. The most common source of institutional authority is government, which derives its authority from sovereign law – the Constitution in the case of the United States. Certain institutions are essential to the emergence of market economies – private property, contracts, money, law, and corporations for example. Other institutions are market-structure specific, and can change both frequently and dramatically. Corporations, the defining economic agents of a modern economy, exist as members of many market-structures and institutions.

Institutions are not only fundamental to economies, but to the very essence of how we, humans, interact with each other. Choices and actions we make today are based on our confidence in knowing what conditions will prevail in the future. An example is driving a car. If we were not certain that other drivers would always drive on the “right” side of the road, obey stop lights, and, in other ways we have come to know and behave predictably, then we would be foolish to risk our lives driving. Driving can only exist if there are rules and constraints making certain everyone’s behavior. These rules and constraints, along with the means for their enforcement, such as licensing rules and the police, enable the institution of driving. Driving is obviously more than just an institution, as it is best if everyone is a competent driver, but without the underlying institutions, people would not drive.

Driving can also be likened to market behavior, with order emerging when people drive cars at high speeds, in traffic, safely, and are able to get from where they are to wherever they want to go with confidence. Since it is impossible to specify exactly what every driver must do, all of the time, institutions can not fully specify driving behavior. Some decisions must be left to the individual drivers, competing and cooperating with all the other drivers who are on the road at the same time. Driving is influenced by both institutions – driving on the right side of the road, stopping where directed, and so on – and the emergence of regularities among the interactions of the individual drivers, such as the fastest cars using the far left lane, or what routes commuters take to and from work.

Economic institutions are created to order interactions of survival and material existence. In a modern economy, institutions are needed to order interactions among collectives, for it is through social organizations, collectives, that man meets his survival and material needs. A collective is any group of persons – or social organizations – whose individual members give up rights and freedoms in return for desired or required collective behavior. Willingness can be either voluntary, as in cooperative behavior, or coerced, in which a credible means of enforcement exists.19 Either way, institutions make future collective interactions more certain. (If an “ideal” behavior exists, it can be additionally incentivized, such as lower car insurance premiums for accident free driving.) And since desired collective behavior changes over time, either intentionally or not, institutions must also change to maintain their effectiveness.

Economic institutions consist of three structural elements – rules, a means of enforcement and informal constraints – and the members constituting the collective.20 Rules define those collective interactions allowed and those not. To have force, the rules must be attended with a credible means of enforcement. And since rules can never fully define every possible interaction, under every set of conditions, members of the collective must make choices and take actions21 they believe consistent with institutional intent. Over time, regularities that arise from member interactions can assume almost rule-like authority, and come to exist as informal constraints – often becoming more important than the formal rules themselves. Examples of informal constraints are: norms, codes of conduct and conventions. Rules will be seen essential to the development of capitalism in the United States; as they are essential to all forms of organized societies.22

The quintessential economic institution of a capitalist economy is private property – private property meaning the right to hold perpetual title of ownership of assets and their improvements, and the right to defend those rights before the law.23 The rules of law define the rights of private property, and the courts are the means of enforcement. Consequently, private property requires a government credible enough to enforce the laws, yet not so strong as to abuse them. Governments create and protect private property in the belief that it is an appropriate way to incent private behavior to promote the “public good.” Consequently, there exists a dynamic between the public’s perception of the value of the benefits received from such an institution, and its continued willingness to support government policies needed to credibly and consistently enforce private property rights.

Private property began as a right enjoyed only by individual “natural persons” – people. When people had need to act as collectives, especially groups whose memberships changed over time, the constraint of natural person-based private property rights became a problem. Collectives needed the right to hold perpetual title to private property, even if their memberships changed. One solution to emerge was the corporation. From initial use over five hundred years ago24 to the end of the twentieth century, corporations have become a principal fixture of modern life, and the central economic agents in capitalist economies.

Capitalist economies also require institutions that promote and protect the exchange of private property – commerce – and the agreements economic agents make between each other – contracts. These three fundamental institutions of capitalism – commerce, contracts and corporations – will be examined historically beginning with the adoption of the U. S. Constitution. Their genesis, while dating to Europe, can be thought to begin with the Constitution for it was only then that they began evolving their modern forms. An example of these institutions in their early development, when America was still a British colony, follows.25

The Massachusetts colony began in 1635 as a corporation chartered by the King of England. The King had innovated corporations to incent private actions thought to be in the crown’s best interests, in this case, people organized to settle America. With time, it became important for the Massachusetts colonial government to promote western migration. So it too resorted to the use of corporations. To incentivize a group of people to brave the hardships and risks of frontier settlement, and establish a permanent community, the colonial governments offered to convert settled land, and any improvements made thereon, to private property in the collective’s – township – name. Each township, once it held title, could then decide how to sub-divide property rights among individual members. At first, every collective held some land back, undivided – the “commons”26 – with which it could attract others to their community. But with time, a problem arose. Many of the early settlers wanted to move West, and increasing numbers of new settlers were moving into existing communities. How then were the commons to be divided?

In 1713, the colony of Massachusettsenacted a statute authorizing “town proprietors and their heirs to organize as an economic body separate from the town government and exercise corporate control over the division of undivided land.”27 Private property rights had been separated from natural and civil rights – private property rights making once public goods no longer “equally” shared by everyone.28 In this example, the township existed as a corporation under contract from the colonial government with the authority to contractually vest private property rights with individuals who could subsequently exchange those rights through commerce.29

- [1]:

Philip Anderson and Michael L. Tushman, “Technological Discontinuities and Dominant Designs: A Cyclical Model of Technological Change,” ASQ, 35 : 604-633. Also Abernathy and Utterback, TBD Dominant design, as will be learned, does not mean best design.

- [2]:

Giovanni Dosi, “Technical Change and Industrial Transformation,” Macmillian Press 1984, p. 15”We will define a technological trajectory as the pattern of ‘normal’ problem solving activity on the grounds of a technological paradigm.” This book looks at the nature of technological and economic change with the world-wide semiconductor industry.

- [3]:

Richard Foster, “Innovation,” Summit Books 1986, p. 31 “The S-curve is a graph of the relationship between the effort put into improving a product or process and the results one gets for that investment.”

- [4]:

Foster., Ibid., p. 98 “learning and diminishing returns.” “The pattern of the S-curve repeats itself again and again in industry after industry.” S-curves are also associated with product life cycles (Arnold C. Cooper and Dan Schendel, “Strategic Responses to Technological Threats,” Business Horizons Feb 1976, p. 62), and diffussion patterns .

- [5]:

Innovating is the set of organizational activities reducing ideas to products.

- [6]:

James March, TBD

- [7]:

Paul A. David, “Clio and the Economics of QWERTY,” The American Economic Review, May 1985 vol. 75 No. 2, and W. Brian Arthur, “Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy,” University of Michigan Press 1994

- [8]:

Nathan Rosenberg, “Inside the Black Box: Technology and Economics,” Cambridge University Press 1982

- [9]:

Rebecca M. Henderson and Kim B. Clark, “Architectural Innovation: The Reconfiguration of Existing Product Technologies and the Failure of Established Firms,” ASQ March 1990, pp. 9 -30

- [10]:

Thomas Kuhn, “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,” University of Chicago Press 1962

- [11]:

Dosi, Ibid., p. 14

- [12]:

Henderson, Ibid., p. 9 “Incremental innovation introduces relatively minor changes to the existing product, exploits the potential of the established design, and often reinforces the dominance of established firms .”

- [13]:

A technological discontinuity, as described in the academic literature, is an innovation that dramatically advances an industry’s price vs. performance frontier (Anderson and Tushman, 1990), destroys the technical competences of existing firms – competence destroying or enhancing – (Landau, 1984; Barley, 1986), and/or “command a decisive cost or quality advantage and that strike not at the margins of the profits and the outputs of the existing firms, but at their foundations and their very lives”.

- [14]:

Henderson, Ibid., p. 9”Radical innovation, in contrast, is based on a different set of engineering and scientific principles and often opens up whole new markets and potential applications .”

- [15]:

Two points: apologies for introducing a “new” term, but it is important to capture the dynamics of process and structure acting and conditioning each other, and being constructed by firms. Second, market structure, without a hypen, is the expression used by economist to denote market concentration.

- [16]:

In fact, AT&T only served 80 to 90% of the market, depending on whether measured as intra or inter LATA, that is local or long distance telephone, traffic.

- [17]:

More accurately, AT&T was not formally organized until 1893. The original organization that became AT&T, the Bell Patent Association, was formed in 1873.

- [18]:

The author’s understanding of institutions. and thus much of this work, is owed to the work of Professor Douglas North; although no representation is made that this work in any way reflects the body of work of Professor North. The interested reader is referred to: “Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance,” Cambridge University Press, 1990; or “Structure and Change in Economic History,” W. W. Norton & Co., 1981

- [19]:

Institutions are therefore also known as authority networks; with market-stuctures becoming exchange networks.

- [20]:

North terminology

- [21]:

**David Lane, Franco Malerba, Robert Maxfield, and Luigi Orsenigo, “Choice and Action.”Unpublished essay, June 27, 1994 pp.

- [22]:

Not woven explicitly into this discussion is the importance of belief systems to the emergence and persistence of rules. A critical belief system in this history is of the relationships of competition and monopolies.

- [23]:

Nathan Rosenberg and L. E. Birdzell, Jr.,How the West Grew Rich:The Economic Transformation of the Industrial World(New York:Basic Books, Inc., 1986) 197.”The right to sue is a necessary and sufficient condition to holding enforceable rights in property and contracts, and the capacity to be sued is a necessary and sufficient condition to incurring legally enforceable duties and obligations by contract.”

- [24]:

The corporation first came into use in mid-sixteenth century England. See: Ronald E. Seavoy, “The Public Service Origins of the American Business Corporation,”Business History Review52 :30-60.

- [25]:

Belief systems

- [26]:

TBD

- [27]:

Seavoy, “Public Service,” 35. “Corporate ownership of land under the 1713 statute appled equally to land speculators and made it easier for them toraise capital from diverse sources, sell shares once a town was settled, avoid most litigation over land titles, and efficiently distribute profits.”

- [28]:

TBD Marx

- [29]:

**Joseph Stancliffe Davis,Essays in the Earlier History of American Corporations(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1917) 66-7:In New Jersey, almost at the beginning of its history as a separate colony, the proprietary governor granted “charters” to the settlers of Bergen(1668)….These documents refer to the settlements as the “Towne and Corporation of Bergen. . .” (or 1965 Russel & russel?)