Chapter 2 - Background

2.11 Computer Inquiry I and the Carterfone -- 1965-1973

By 1965, the convergence – and potential conflict – between common carrier communications and computers began making an impression on Strassburg, Chief of the CCB of the FCC since 1963. He would write later of how he then viewed the relationship between AT&T and the FCC: “It was truly a symbiotic relationship. The regulated monopoly operated in what was considered to be the public interest and, in turn, was shielded against incursions by rivals and competitors, including the possibility of government ownership.”434 He had reason to be satisfied, for interstate rates, a key measure of FCC effectiveness, had been consistently declining. Even so, Strassburg couldn’t get out of his head what Dr. Manley Irwin, a young economist on his staff, kept telling him – computer users wanted to use the telephone system in ways AT&T had consistently fought. Strassburg recalls:

I, in 1965, assembled a task force, a small group of staff members to sort of take an overview of the various dimensions of data communications; what the problems seemed to be, if any, and what we should do about them.435

Bunker-Ramo Corporation (BRC) gave the task force immediate relevance when it announced Telequote IV.436 BRC wanted to offer computer services to brokerage firms that would allow branch offices to send stock quotes, transactions, and messages to central computers and terminals located in other branches. WU and AT&T, BRC’s common carriers, refused to provide the private lines needed to implement their system; arguing that BRC wanted to provide message switching services which they could not do under existing common carrier tariffs, and to do so, they would become subject to regulation under the Act of 1934. (Fighting the combination of common carriers, the FCC and PUC’s proved exhausting, and facing little hope of success, BRC in February 1966 introduced a modified Telequote service.) BRC’s frustrations were far from unique, as the task force was quickly learning.

In February 1966, the United States District Court, Northern District of Texas, referred a case to the FCC under the doctrine of primary jurisdiction to resolve questions of whether the tariff permitting telephone companies to suspend, or terminate, service if non-AT&T devices were connected to telephone company facilities was valid. Once again it was the issue of foreign attachments, and the case was: Thomas F. Carter and Carter Electronics Corporation v. American Telephone & Telegraph Company et al.

To his friends, Tom Carter was a practical man, an inventor and entrepreneur. But a David about to get the best of Goliath, never. Carter’s innovation was motivated by the simple desire to solve the communication problem of oil field workers, far from phones, maybe aboard an off-shore oil-rig, trying to reach home. Or to get a message to their office. “We’ve struck oil!” Carter’s clever kludge – the Carterfone437 – was hardly a lightning rod it will to prove to be.

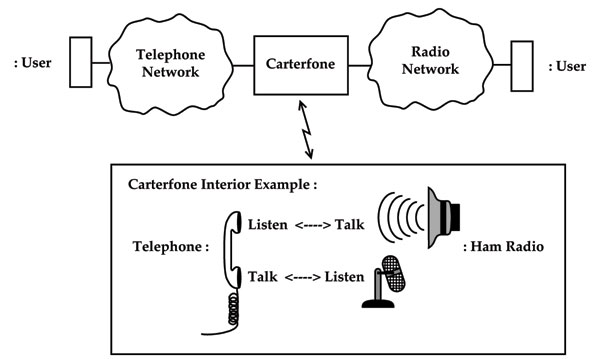

The Carterfone was simply a mobile radio that was connected acoustically, or inductively, to the telephone network. (See Exhibit 2.17 - The Carterfone) Without any electrical connection or wiring or physical attachment, an incoming telephone call activated a two-way radio connection which permitted the telephone caller to communicate with someone using the radio system.

Exhibit 2.17 - The Carterfone

When Carter first introduced the Carterfone in 1959, he had been surprised to learn that the telephone company held the Carterfone could not be connected to the telephone network – it interfered with their end-to-end service responsibility and could be harmful to telephone service. Furthermore, it violated the tariffs banning foreign attachment.438 Carter was not so easily discouraged, and by 1966 had sold approximately 3,500 Carterfones in the United States and overseas. Nevertheless, the Bell System or General Telephone threatening to terminate customers telephone service posed a real obstacle to sales, so in 1966, Carter brought an antitrust suit against the Bell System and the General Telephone Company of the Southwest.439

Once at the FCC, the Carterfone case was referred to the CCB where it received scant attention. Understandably so, since the CCB already had an extremely busy agenda, including: the first ever general rate inquiry of AT&T, begun in 1965; the Telpak tariff controversy, initiated in 1961 (this issue alone will take twenty years to resolve); a request by Microwave Communications, Inc. (MCI) for a license to offer common carrier services between St. Louis and Chicago in competition with AT&T, filed in 1963; the just launched domestic satellite inquiry; and the task force looking at the issues of computers and communications. Hearings to collect information for the MCI and Carterfone cases were scheduled for 1967.440

Meanwhile, Strassburg was coming to the opinion that: “Few products of modern technology have as much potential for social, economic, and cultural benefit as does the multiple access computer.”441 Knowing he had to educate the Commissioners to the needs of computers, he contacted the Institute of Electrical Engineers (IEEE)442 to give a series of lectures to the Commissioners. One of the lecturers was Paul Baran, who was known to Strassburg, and as future chapters will make clear, a dominant figure in the history of computer communications.

Strassburg began publicly airing his opinions. On October 20, 1966, he gave a speech to an audience of computer professionals in which he identified three unresolved issues in the coming convergence of computers and common carrier communications: who could compete in what businesses – the issue of market entry; communication line costs; and information privacy. He also clarified his understanding of the responsibilities and roles of the FCC, or Commission, as well as their responsiveness to the issues:

The Commission is not indifferent to these concerns. On the contrary, the matters involved are the subjects of our active study with a view to determining the respects in which the tariff offerings of the carriers may fall short of meeting, on a just and reasonable basis, the communication requirements of the data processing industry. For the Commission is obliged by the policies and the objectives of the Communications Act to ensure that the nation’s communication network is responsive to the requirements of an advancing technology. The Commission has the obligation, the authority, and the means to reappraise and refashion any established policies in order to promote the public interest through an effective realization of the social and economic benefits of current technology.443

Strassburg’s speech served as but a warm-up for the announcement on November 9 that the FCC would hold a public inquiry titled: Notice of Inquiry, In the Matter of Regulatory and Policy Problems Presented by the Interdependence of Computer and Communications Services and Facilities (Docket F.C.C. No. 16979). Strassburg remembers:

I decided that we ought to formalize this thing. We sensed enough ferment out there, or enough concern, to say: ‘Well, look we’re going to encounter some problems here, and let’s get on top of them sooner, rather than later, and for once let a regulatory agency be out in front, rather than trying to shovel up the mess that’s left behind.444

Unsure if they had captured all the salient issues, the CCB first circulated a draft of the Notice. Hoping to learn how the fast growing data processing industry wanted to use the telephone system, as well as how data processing firms viewed AT&T offering data processing services,445 the Notice read:

We are confronted with determining under what circumstances data processing, computer information, and message switching services, or any particular combination thereof–whether engaged in by established common carriers or other entities–are or should be subject to the provisions of the Communications Act.446

In early 1967, H. I. Romnes became AT&T’s new Chairman and Chief Executive Officer.447 Romnes did not fully subscribe to AT&T’s long standing policy opposing foreign attachments. Shortly after taking office, he expressed the opinion that Bell’s responsibility for the network could be maintained if there were used suitable interfaces or buffer devices to keep the attached equipment from affecting other users of the network.448

Over forty organizations responded to the draft Notice, including AT&T, IBM, Bunker-Ramo and WU.449 The comments raised no new issues, so the Notice was reissued on March 1, 1967, with final comments requested by October 2, 1967.

The MCI hearings began in February and lasted nine weeks. The Carterfone hearings were scheduled next, for April.450 Fred Henck, Editor of Telecommunications Reports,one of the most respected trade publications of the time, would comment later that it was hard to find someone to report on these two insignificant cases, referred to around the office as the cats and dogs.451

Strassburg, on the other hand, began to see the Carterfone as a way to revisit the foreign attachments tariff, which, as he was increasingly learning, was a real impediment to data processing use of the telephone system and to innovation of communication devices.

We used the Carterfone issue and the Carterfone proceeding as a vehicle for revisiting the basic policy, which was basically a Bell System policy, which had been embraced by the FCC and the regulatory commissions for many generations, against customers, willy-nilly, interconnecting anything they chose to the telephone network, no matter how innocuous it might be unless the item was specifically authorized by the telephone company’s tariffs.

Well, the telephone company wasn’t likely to tariff anything of consequence, so as a result, anytime anybody wanted to promote a piece of equipment and to have it work with the telephone network, they either had to sell it to the Bell System, if they could convince Western Electric and Bell that they had something sellable, or if they couldn’t succeed in that channel, then attacking the tariff insofar as the claim was unlawful – and that the Commission should order it amended in order to accommodate their device. But that was a very cumbersome process to go through; the administrative hearing and the time and the cost involved that, to a small entrepreneur with a piece of equipment – it discouraged people. It discouraged the market from developing, and that’s why, I think, the United States was so far behind other countries, because, in terms of customer-premise equipment, simply because there was no entrepreneurship, the entrepreneurship was blunted and discouraged by this institutionalized practice of saying: “You can’t connect with us.” In other words, everything that went on had to go on within the Bell System, Bell Laboratories.That was where innovation began and ended.452

When it came time to argue the Carterfone case before the Hearing Examiner, Chester F. Naumowicz, Jr., the CCB took the position that the tariff provisions limiting use of customer-provided equipment be canceled. Replaced, instead, with a tariff provision that ‘clearly and affirmatively states…that customer-provided equipment, apparatus, circuits, or devices may be attached or connected to the telephones furnished by the telephone company in the message toll telephone service for any purpose that is privately beneficial to the customer and not publicly detrimental.453

The CCB was not arguing that users could substitute customer-provided equipment for that provided by the telephone company, only that it should be permissible to connect or attach devices to telephones furnished by the telephone company.454

AT&T was not alone in fighting the liberalization of foreign attachments. For example, the National Association of Regulatory and Utility Commissioners (NARUC) testified that a ruling against AT&T would cause a tremendous rise in administrative costs and force changes to existing tariffs. Individual state PUC’s also testified in support of AT&T.455

The Carterfone hearings took but seven days. Maybe sensing a fundamental change in progress, Romnes assembled a high-level Tariff Review Committee to conceive alternative interconnection tariffs that would protect the network.456 The facts that AT&T permitted connection of foreign attachments by the military and government, as well as equipment of TV networks, all suggested there had to be a solution other than total prohibition.

In August 1967, Examiner Naumowicz, issued his initial decision. Ignoring the argument for a broad policy change, he ruled narrowly that harm from use of the Carterfone had not been proven: ‘We here consider on a specific device and the evidence as to what, if any, effect it will have on the system.’“457

By the Fall, responses to the Notice of Inquiry were pouring into the FCC. It was as if a sensitive nerve had been struck, and the press could not get enough of it. An already burdened CCB saw thousands of pages of input and exhibits piling up, ever impossible to ignore, especially with the Commissioners relishing their new found popularity and kudos for public leadership. As CCB staffers began leafing through the materials, two subjects came up again and again: the prohibition on foreign attachments were unduly restrictive, and telephone rate structures were designed for voice, not data, communications. To those reading the reports, it became patently clear the CCB had neither the resources, or expertise, to make sense of the fifty-five responses, so Stanford Research Institute, International (SRI), a think tank and consulting firm on the West Coast, was contracted to do the analysis. Unmistakably, however, changes in market conditions and technologies were challenging the status quo – any broad policy implications, however, would have to wait for the SRI report, not expected until March 1969.

Meanwhile, those users brave enough to try timesharing found themselves caught in a no man’s land between the time-sharing firms and the telephone companies. One such story was told in the May 1968 issue of Datamation,458 a leading trade magazine:

SOME PROBLEMS WITH TIME-SHARING by BRYAN WILKINSON

Late in 1966 our bank decided to experiment with commercial time-sharing, looking toward the day when our 360 branch banks would be linked to a central computer. I was given the responsibility for this experiment. There are two major telephone companies operating in the Los Angeles area and at least five companies selling commercial time-sharing service. We contracted with one of the larger, more experienced time-sharing vendors. Only one of the two telephone companies was involved.

Our system was installed in February 1967……..The next day the potential users in our company and I were given a four-hour briefing on a simplified programming language and the system operation. We were handed three manuals (none of them indexed), and we were ‘experts.’

The terminal, besides being an inexpensive, sturdy machine, allows one to enter programs or data by paper tape. It was our intention to have these tapes prepared by the secretaries so we asked who should train them. The time-sharing people indicated the telephone company, and they agreed. Fortunately, I decided to sit in on this session because the telephone company’s training representative started to teach our secretaries how to use the terminal as a teletypewriter, not as a time-sharing device. (The differences are considerable and confusing.) When I asked the instructor to cover only the relevant items, she was at a loss. She knew nothing about time-sharing. It developed that each time-sharing company makes special use of some of the characters so that only they could give adequate training about those things. Here, on our initial day of operations, we ran into the first of many vendor coordination problems. The time-sharing people could train on how to use their system; the phone company could train on how to use the terminal; but no one could give complete training. Until this could be resolved (and five months later it hadn’t been) the idea of using secretaries had to be shelved.

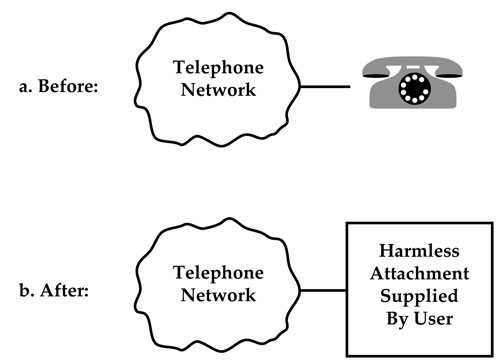

Whether emboldened by the unaccustomed favorable press, or now sensing a sea change about them and it was time to lead, the FCC Commissioners on June 27, 1968, in a surprising and unanimous decision, despite last minute lobbying by AT&T and GTE that the integrity of the telephone system necessitated the use of only carrier-supplied attachments,459 ruled in the Carterfone case that the tariff restrictions:

are, and have since their inception been, unreasonable, unlawful, and unreasonably discriminatory under the Communications Act of 1934.”460

WHAM. (See Exhibit 2.18 - The Carterfone Decision ) The Commission went on:

…The vice of the present tariff…is that it prohibits the use of harmless, as well as harmful devices.

In view of the unlawfulness of the tariff, there would be no point in declaring it invalid as applied to the Carterfone and permitting it to continue in operation as to other interconnection devices. This would also put a clearly improper burden upon the manufacturers and users of other devices. The appropriate remedy is to strike the tariff and permit the carriers, if they so desire, to propose new tariff provisions in accordance with this opinion…….The carriers may submit new tariffs which will protect the telephone system against harmful devices, and they may specify technical standards if they wish.461 462

AT&T responded to the FCC’s Carterfone decision:463

We have had the whole subject of connection of customer-owned devices in our network under intensive review for some time. Our intent is to be as responsive as possible to evolving communication needs through making our network available to expanding uses. At the same time, safeguards are essential to assure that other users of the network are not adversely affected.464

Exhibit 2.18 - The Carterfone Decision

Formally, AT&T and GT&E responded by seeking FCC reconsideration. On July 29, 1968, the FCC stayed their decision awaiting the disposition of the petitions for reconsideration from AT&T and GT&E.

In August Datamationreported the FCC decision as:465

FCC CARTERFONE DECISION UNSETTLES CARRIERS, ENCOURAGES MODEM MAKERS. - Datamation August 1968

The FCC dropped one shoe June 26 when it decided that Ma Bell’s foreign attachment restrictions are unnecessary, and unfair to users; last month, computer users and foreign attachment manufacturers were waiting for the other shoe to fall.

Experts familiar with the arcane world of communications utility regulation agreed that the next move was up to the carriers. As one lawyer put it: ‘the commission has blasted a gaping hole in the tariff wall, leaving the carriers dangerously exposed. At this moment, any user could hang any foreign attachment on his telephone line and not worry too much about getting arrested.

He added, however, that the user would be hurting himself as well as the telephone company. ‘The carriers lost largely because they couldn’t prove that foreign attachments were harmful. Almost certainly, they will now be looking doubly hard for such evidence in the hope of persuading a judge to overturn the commission’s ruling.

Then later in the same article:

The ruling, if it stands, breaks the market for modems wide open, and provides a major opportunity for independent manufacturers in areas like touch-tone keyboards and picture-phone type units. There are no authoritative figures on the number of Western Electric’s modems in the dial-up network, but one manufacturer says that’s where 90% of the business is. Among data set suppliers are General Electric, which announced an extensive line late last year, Automatic Electric, Milgo, Rixon, Collins Radio, and Ultronic.

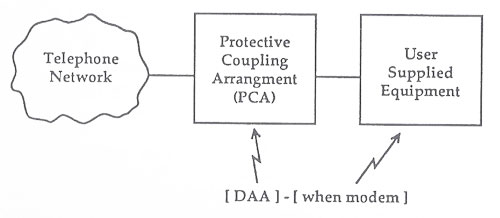

In August, AT&T Board Chairman H. I. Romnes and President Ben Gilmer held a press conference, proposing a “new ‘data access arrangement,’ under which independently manufactured terminals could be coupled electrically, inductively, or acoustically to the public telephone system through a ‘protective device’ and a ‘network controller.’ The data communications user would pay $10 to have the protective device installed, and $2 a month for the service……Both devices are to be supplied exclusively by the Bell system, and no one else apparently will have any say in their design.”466

In September, the FCC asserted its decision: devices that did not adversely affect the telephone company’s operations, or the telephone system’s utility for others, could be connected to the interstate telephone system.467

In an article published that Fall, Strassburg wrote:

An important principle for the computer user is involved in this case. The telephone system is the essential means by which users remote from the computers can have direct access to that computer. In order to create compatibility between the computer and the telephone circuit, it is necessary to use a ‘modem’ or modulator/demodulator. The telephone company requires that its own modem - the dataphone - be leased for this purpose. Computer manufacturers and users would like to furnish their own modems for many reasons which we need not detail. The telephone company permits extensive connection of computer and computer related devices to its telephone system, but the user must interface to the system with a dataphone - the device manufactured by Western Electric and available from the operating companies of the Bell System on a rental basis. A decision by the Commission to relax the restrictions on the customer’s use of foreign attachments would expand the opportunity for wider participation in not only the computer equipment market, but in the communications equipment market generally.468

In November, AT&T filed new tariffs that far exceeded the expectations of the FCC. Customers will be allowed to directly connect terminal equipment469 to the public switchednetwork provided they connect using an AT&T supplied protective connecting arrangement (PCA). (See Exhibit 2.19 - AT&T Carterfone Tariff.) As Strassburg later testified: “AT&T went well beyond the requirements of Carterfone.” The FCC ruled before the year-end holidays that the new tariffs would become effective January 1, 1969.470

Exhibit 2.19 - AT&T Carterfone Tariff

Once the new tariffs became effective, AT&T announced that the PCA for modems would be called a Data Access Arrangement, or DAA. DAA’s had two primary functions: assure telephone network integrity by limiting the signal power of attached modems to a level that would not exceed the power-level of the network, and maintain exclusive Bell control of all network signaling functions.471 To be installed only by Bell personnel for a modest fee, and to rent for $2 to $4 per month, DAA’s were a single circuit board that came with a separate telephone set having a voice/data key. All network connections had to be made manually and there were no provisions for either automatic dialing or unattended answering; even though Bell modems had these functions. So while the DAA’s made it possible to connect independent manufacturers modems to the switched telephone network for the first time, they severely constrained modem functionality and introduced costs not incurred using Bell modems – for Bell modems did not require DAA’s.

Immediately there were protests. Why should modems of independent manufacturers be burden with extra costs and reduced functionality? Bell was up to its old tricks again, only now there were affected parties who were not going to let Bell get away with it. What seemed particularly preposterous to those independent modem manufacturers selling modems to telephone companies was that their modems would now have to be re-engineered to work with DAA’s. Where was the logic that made it possible for them to sell a modem to a telephone company, which could sell it to a customer, but the modem manufacturer could not sell the very same modem to that same customer? In response, AT&T claimed: If we provide it, we maintain it and we know it’s going to work right. If the customer provides it, he might not maintain it, and a short might cause a voltage surge on the line which might kill somebody.472

As sympathetic as the CCB staff were finding themselves becoming, the new AT&T tariffs were already more liberal than anyone would have thought possible only months earlier, and too much was at risk to proceed willy-nilly. Strassburg remembers telling those complaining: “Well, you may be right, but this is where it is right now, and until we find a better alternative, this is where it’s going to stay, because we’re not going to open up the network to indiscriminate connections for fear that this would degrade the performance of the network.473

Standing arm-in-arm with AT&T might have been past practice, but now the CCB wanted independent assessment of alternatives to PCAs, freeing them from their dependence on AT&T’s recommendations. Seeking the most impartial, technically competent organization, the FCC contracted with the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) to study the tariffs and to recommend alternatives.474 A report was expected in about a year, with hearings scheduled for September.

During this same period, February 1969, the FCC received the SRI report475 commissioned to analyze the responses to the Notice of Inquiry. The report was too technical and detailed to be understood by anyone at the FCC or CCB. So Strassburg, once again, sought out Baran, who had since left Rand and started the Institute for the Future (IFF) – Romnes, of AT&T, was a member of IFF’s Board of Trustees. Baran agreed to interpret the report.

Shortly after taking the assignment, AT&T offered Baran’s IFF a lucrative, and interesting, consulting contract. Needing the work, Baran notified the FCC of his potential conflict of interest and ceased being a consultant.476 The AT&T assignment was to study its management practices and to contribute as required. Baran remembers:

I think it was very useful because they were able to get some inputs in how they are really perceived…..and that their real problem is going to come from the data communication entrepreneurs, because now, for the first time, they had a constituency who might perceived it worth their while going after AT&T. The old constituency in the past was never big enough, or had enough interest, to attend hearings or doing anything, but now you have these new entrepreneurs coming along and that you’re probably better off giving in to them and not threaten the rest of your system.

With Baran’s help, in May, the FCC issued the Report and Further Notice of Inquiryto solicit opinions on the SRI study. Respondents’ comments added little to the FCC’s understanding.477 The CCB now had the task of deciding what actions they should, and would, take as a result of collecting the comments and materials through its Inquiry. The CCB, and thus the FCC also have to deal with all the other common carrier workload. (In August, the FCC will approve the license of MCI to operate a competitive common carrier service between St. Louis and Chicago.478 Often referred to as either the MCI, or SCC (Specialized Common Carrier), ruling.479 )

Strassburg remembers his perspective changing during this period:

We, I at least, felt there was a compelling reason to be concerned about certain trends that were out there, that Bell couldn’t be all things to all people for all times. That the environment had changed, or was changing, and that innovation and creativity didn’t all start within the walls of Bell Labs, and all the wisdom wasn’t necessarily in Bell Labs. We were also concerned – I was concerned that AT&T was beginning to grow big, in terms of not only revenue – they had always been dominant as a corporate power – but at this time it was getting awfully big, so was there room for other participants in this marketplace called communications?

On April 3, 1970, the FCC issued its Tentative Decision and Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, 28 F.C.C. 2d 291 (1970) or the “Tentative Decision.” The entire proceedings become popularly known as the “Computer Inquiry.”480 Public argument of the Tentative Decision was scheduled for September 3, 1970, and March 18, 1971.

The Tentative Decision addressed four key issues: Data Processing Computer Services, Common-Carrier Provision of Data Processing, Store-and-Forward Message-Switching Services and Hybrid Services.481

Data Processing Computer Services

All agreed that data processing did not exhibit economies of scale as did natural monopolies such as telephone exchange services. Therefore, the FCC concluded: “…in view of all the foregoing evidence of an effective competitive situation, we see no need to assert regulatory authority over data processing facilities in order to link the terminals of subscribers to centralized computers.”482 The Commission retained the prerogative to “re-examine the policies set forth herein…if there should develop significant changes in the structure of the data processing industry.”

Common-Carrier Provision of Data-Processing Services

A more complicated issue and one that would remain unresolved until the Final Report. The problem came when common carriers wanted to engage in unregulated activity. How could economically motivated cross subsidies from regulated to unregulated businesses be avoided?

Store-and-Forward Message-Switching Services

The FCC concluded message-switching services were “essentially communications” and “warrant appropriate regulatory treatment as common carrier services under the Act.”483

Hybrid Services

Hybrid services were those having both data processing and message-switching components. The Commission, using a “primary business test,” said: “Where message switching is offered as an integral part of, and as an incidental feature of a package offering that is primarily data processing, there will be total regulatory forbearance with respect to the entire service whether offered by a common carrier or non-common carrier, except to the extent that common carriers offering such a hybrid service will do so through [separate] affiliates…..If, on the other hand, the package offering is oriented essentially to satisfy the communications or message switching requirements of the subscriber, and the data processing feature or function is an integral part of, and incidental to message switching, the entire service will be treated as a communications service for hire, whether offered by a common carrier or a non-common carrier and will be subject to regulation under the Communications Act.”484

In September, the FCC heard oral arguments on the Tentative Decision from some twenty interested parties.

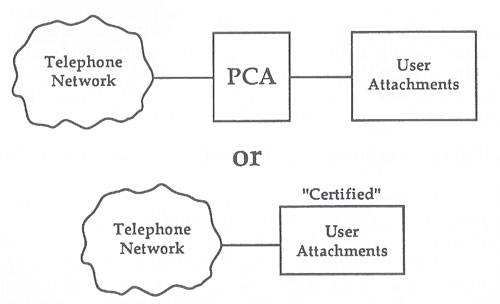

In June, 1970, the FCC received the NAS report485 commissioned in response to the uproar over the tariffs filed by AT&T requiring the use of DAA’s. (See Exhibit 2.21 - NAS Recommendation.) The report concluded:

1) Uncontrolled interconnection could cause harm to personnel, network performance, and property. 2) The use of protective couplers and signal-level criteria was an acceptable way of assuring network protection; however, the added equipment increased overall costs. 3) A program of standards and enforced certification of equipment would be another acceptable way of assuring network protection.

A subsequent study commissioned by the FCC to Dittberner Associates, a Washington-based firm of computer consultants, concluded that manufacturers of data modems and other types of interconnected customer equipment could easily build into their equipment the necessary circuitry to protect the telephone network – the common carriers need not be the only ones providing network protective couplers.486 Furthermore, a program of standards and certification would be an inexpensive way to extend interconnection privileges without harm to the common-carrier network.

Both the NAS and Dittberner reports agreed, safe attachment of customer provided equipment could be accomplished without the objectionable carrier-supplied access arrangements or PCAs.487 Knowing an alternative to the PCAs existed, and given no cessation of complaints – long delays in getting PCA’s installed, too expensive, and constantly changing interface specifications – the CCB needed a plan of action. Due to manufacturer and customer interest, PBX standards and certification procedures were selected to be first. On March 26, 1971, the FCC established a PBX industry advisory committee with some thirty members representing carriers, equipment manufacturers, and users. This committee had the responsibility to devise technical standards, as well as certification and enforcement procedures permitting direct connection of PBX equipment to the telephone network – without using PCAs.488

In that same month, on March 18, 1971, the FCC, in a divided 4 to 3 vote, rendered its Final Decision in the Inquiry.489 (Final Decision, 28 FCC 2d 267 (1971)). In it, the FCC introduced the concept of”maximum separation”490 to solve the problem of common carriers wanting to provide data processing services. To compete in the unregulated field of data processing services, common carriers could only do so through separate subsidiaries with separate books of account, separate officers, separate operating personnel, separate equipment, and facilities devoted exclusively to the rendition of data processing services.491 These subsidiaries would lease communication services from carriers (the parent company or any other carrier) under public tariffs, just like competing suppliers of data-processing services.492 Issues remained, however, particularly those of “hybrid services.” But in general, the regulatory issues between data processing and communications seemed settled.

Exhibit 2.20 - NAS Recommendation

As is customary with FCC determinations, the common carriers filed petitions for judicial review of the Final Decision. Arguments before the court will be held in the Fall, and the Second Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals will issue its decision – “essentially” upholding the commission’s determinations – on February 1, 1973.493

As much as the FCC wanted to proceed in an orderly fashion, events soon took a life of their own. The cause – two proposed tariffs filed by AT&T in late 1971. The first mandated use of DAA’s on leased lines that had to-date been exempt from the PCA tariffs. Interestingly, leased lines were also the facilities experiencing the most competition from the independent modem manufacturers; a connection not lost on the modem manufacturers. The second tariff lowered modem rental rates.494

Michael Slomin, lawyer at the FCC working closely with Strassburg on the issues being discussed, remembers the just then forming cooperative of independent modem and other data communication manufacturers, the Independent Data Communications Manufacturers Association (IDCMA) crying:

This is manifestly anti-competitive. This is evidence of a grand master plan to wipe us out, and furthermore, its predicated on a false premise anyway. This data access arrangement is ridiculous. It’s not needed. Our devices are designed properly to work with the telephone network, indeed, our companies sell them to about a hundred governments abroad for use with their telephone networks and there’s no problem whatsoever. And finally, the data access arrangement is a Cadillac when a Chevy would have done the job. It has extra functions and, on top of all else, it impairs our communications. It introduces its own aberrations and makes our communications service stinky. Do something about this, FCC.

Competitive outrage could no longer be contained within the deliberative proceedings of the FCC – antitrust lawsuits soon began clogging the courts. And as justice seemed too slow or uncertain, the battleground moved to Congress with its power to change the laws. These consequences flowed directly from the FCC changing the rules of competition – especially those of foreign attachments and SSCs.

- [434]:

Slippery Slope p XI

- [435]:

Interview

- [436]:

Stone, pp. 202-205. Also:”AT&T and Western Union refused to permit the use of their communications services by Bunker Ramo for these additional message-switch functions. They took the position that Bunker Ramo would be engaging in the provision of a communications service for hire and, as such, would be subject to certification and regulation under the Communications Act. Further, AT&T and Western Union contended that the use of their facilities, as proposed by Bunker Ramo, would be contrary to provisions in the carriers’ tariff regulations which barred their customers from reselling communications service. AT&T and Western Union prevailed in the dispute and the enhanced services of Bunker Ramo were foreclosed.” Common Carrier, page 190

- [437]:

The literature has the spelling both Carterfone and Carterphone.

- [438]:

A Slippery Slope, p.97

- [439]:

Regulatory and Economic Issues in Computer Communications,” Proceedings of the IEEE, November 1972, p.12

- [440]:

See a Slippery Slope for a much more detailed discussion of these issues and more.

- [441]:

October 1966 Speech, Jurimetrics Journal, September 1968, pp. 12-18

- [442]:

A professional organization.

- [443]:

October 1966 Speech, Jurimetrics Journal, September 1968, pp. 12-18

- [444]:

Interview. The most dominant issue for the FCC is the allocation of radio frequencies.

- [445]:

A Slippery Slope, p.141

- [446]:

FCC 66-1004

- [447]:

Give background etc Temin, pp. 44-45

- [448]:

Temin, p. 44

- [449]:

FCC 67-239

- [450]:

Slope, p. 101

- [451]:

Slippery Slope pg. 102 Henck: “AtTelecommunications Reports, we reflected the view of our news sources that neither case was very important. Our main problem was finding someone on our small staff with enough time to cover what we considered rather insignificant hearings. Along with a few other minor cases going on at the time, the Carterfone and MCI hearings were referred to generically in the office as “cats and dogs.”

- [452]:

Interview

- [453]:

Slippery Slope, pgs 104-105

- [454]:

Strassburg interview:”We were also being very cautious in how far we thought the tariffs ought to be amended and how far we ought to go. We didn’t view the issues in Carterfone as having to do with any replacements or substitutions for the equipment provided by the telephone company. It was how the telephone service provided by the telephone company, including the instrument, the terminal, should interface with other equipment and under what circumstances it should permit connection to other equipment which it didn’t provide.

- [455]:

Stone. p. 149

- [456]:

Temin, p. 44

- [457]:

Slippery Slope pg. 105

- [458]:

Datamation, May 1968, pp 43-45

- [459]:

Regulatory and Economic Issues in Computer Communications,” Proceedings of the IEEE vol. 60, November 1972., p. 1266

- [460]:

“Regulatory and Economic Issues in Computer Communications,” Proceedings of the IEEE vol. 60, November 1972., p. 1266

- [461]:

Ibid., pp. 1266-1267

- [462]:

The FCC language also left open the possibility of future lawsuits against the telephone companies: “has been unreasonable, discriminatory, and unlawful in the past.” This matter is settled without suits.

- [463]:

Brooks, p. 299 : General Counsel Moulton, chief of the AT&T legal team that argued against the Carterfone decision, says of it, That’s one I’d rather forget, and adds that it is a fair question whether AT&T could have headed off the far-reaching decision by amending its tariff in advance. Such a move, he concedes, would have required a revolution in thinking inside AT&T, which believed – and indeed had long been encouraged to believe – that the public consensus favored treating the telephone business in all its aspects as a regulated monopoly.

- [464]:

Slippery Slope p106

- [465]:

Datamation, August 1968 pp 86-87

- [466]:

TBD

- [467]:

Slippery Slope pg. 106

- [468]:

“Competition and Monopoly in the Computer and Data Transmission Industries” Bernard Strassburg, The Antitrust Bulletin, Vol XIII Fall 1968, pgs 996-997

- [469]:

Subsequent discussion will focus on modems for they constitute a key product of the first paradigm of computer communications – data communications.

- [470]:

Shortly after the tariffs went into effect, accepted by the FCC, the parties to the Carterfone antitrust lawsuit settled out of court. Carter et. al received a reported $375,000; they had sued for $1,350,000. A little over a year later, Carter left his firm to consult. Henck p. 107

- [471]:

Data Pro 1970, Computer Conversions Inc., All About Modems, 70F-300-01b

- [472]:

Thomas Thompson Interview: This is the type of horror stories they always raised.So that was what we were stuck with. We were stuck with the DAA.”

- [473]:

Interview

- [474]:

Henck, p. 107 :NAS had its Computer Sciences and Engineering Board set up a fourteen-member panel to analyze the considerable amount of written material submitted to the FCC. The fact that panel members were not ‘pure’ scientists in the sense that they drew paychecks immediately caused criticism. It was a symbol of changing attitudes that most objections were raised because two of the fourteen panelists were officials of the Bell System. The others were employed by nonprofit and/or government organizations, non-Bell manufacturers, independent telephone companies, or large users of communication services.”

- [475]:

Stanford Research Institute, Policies and Issues Presented By the Interdependence of Computer and Communications Services (Report Nos. 7379B0. 7 vols.

- [476]:

Baran interview:”Here I was working for the FCC and along came this contract from AT&T, for the Institute for the Future, and we needed that work, so I told my friends at FCC that I would no longer be able to be a consultant to them, and they said: “Well, we understand, but why don’t you become a general consultant to us on research and development, because we’re not doing a very good job with research and development at the FCC and we could use some help, and that should be clean and shouldn’t give you any problem with conflict of interest.” So I said, “OK.” And I said: “First of all, how much are we paying, what would have been the Chief Engineer.” They said $25,000. And I said: “Well, that’s not enough money to get the sort of person you really need for that top position.” They said: “We know, but the Congress dictated that. It’s in the legislation, and that was done purposely, because about 25% of the congressmen had some interest or other in a broadcast station, or TV, a very high correlation. It was very important to their political position. So, there was a nice strong political constituency that wanted to see the FCC weak for some time, and so that was a constraint. So I said: “Well, no, until you get this problem fixed, there’s hardly very much you can do,” cause the people they had were just, they were technicians. So I didn’t do a lot more consulting after that one.”

- [477]:

Regulatory and Economic Issues in Computer Communications, “IEEE vol. 60, pp 1256, November 1972.

- [478]:

“The FCC’s approval of MCI triggered a flood of over 1900 new microwave-station applications by several dozen firms proposing to build more than 40,000 miles of new specialized-carrier communications facilities throughout the country. All but one of the applicants (16 of whom are affiliated with MCI) proposed MCI-like analog microwave facilities that would offer a variety of business-oriented private-line communication channels, as well as channels specifically designed for data transmission. The exception was the Data Transmission Company, or Datran , which proposed to build a nationwide all-digital switched network to offer exclusively data-transmission services on both a switched and private-line basis.”Regulatory and Economic Issues in Computer Communications, “IEEE vol. 60, pp 1266-67, November 1972.

- [479]:

The historical trajectory of MCI and the SCC’s is as interesting, and complements, the story being told herein of CPE. The reader is referred especially to Temin and Henck.)

- [480]:

Only years later, when additional Inquiries are held, will this Inquiry be referred to as Computer Inquiry I.

- [481]:

This text is either direct or indirect citation from: Regulatory and Economic Issues in Computer Communications, “IEEE vol. 60, pp 1257-1261 November 1972.

- [482]:

28 FCC 2nd 291 , at 298

- [483]:

62 One example of a message-switching service which, if offered on a commercial basis to the public at large would, under the Commission’s present rules, have to operate as a common carrier, is the computer network of the Advanced Research Projects Agency .See Chapter 5 for the history of the ARPA network.

- [484]:

28 FCC 2nd 291 , at 305

- [485]:

National Academy of Sciences, Computer Science and Engineering Board,A Technical Analysis of the Common Carrier/User Interconnections Area,Rep. to the FCC, June 1970

- [486]:

Dittberner Associates,Interconnection Action Recommendations,Rep. to the FCC, Sept. 1970

- [487]:

Regulatory and Economic Issues in Computer Communications, “IEEE vol. 60, pp 1257-1261 November 1972.

- [488]:

Regulatory and Economic Issues in Computer Communications, “IEEE vol. 60, pp 1257-1261 November 1972.

- [489]:

Common Carrier pg. 191

- [490]:

Computer Law Service, The Computer Inquiry-The Regulatory Results, Bernard Strassburg, Callaghan & CO, 1973, pgs 2-3: “Thus, the commission invoked the doctrine of ‘maximum separation’ by which to insure that the regulated activities of the carrier are in no way commingled with any of its non regulated activities involving data processing……..Essentially, the degree of separation required by the commission was premised on the following regulatory concerns: (1) that the sale of data processing services by carriers should not adversely affect the provision of efficient and economic common carrier services; (2) that the costs related to the furnishing of such data processing services should not be passed on, directly or indirectly, to the users of common carrier services; (3) that revenues derived from common carrier services should not be used to subsidize any data processing services; that the furnishing of such data processing services by carriers should not inhibit free and fair competition between communication common carriers and data processing companies or otherwise involve practices contrary to the policies and prohibitions of the antitrust laws.”

- [491]:

28 FCC 2nd 267, at 270

- [492]:

Regulatory and Economic Issues in Computer Communications, “IEEE vol. 60, pp 1257-1261 November 1972.

- [493]:

Common Carrier pg. 191. GTE Service Corp. v. F.C.C., 474 F. 2d 724

- [494]:

Datapro “All About Modems” 1971 pg. 01c

- [495]:

Interview