Chapter 14 - Internetworking: Emergence 1985-1988

14.8 The NBS in Action: OSINET, COS, and GOSIP

OSINET development was behind schedule since needed resources had been reassigned to Autofact.33 With the demonstration now over, NBS changed its budget priorities as well as solicited resources from voluntary participants; those who grasped the importance of a functioning OSINET. The objectives of OSINET were to: verify tests results, facilitate vendor-to-vendor testing and perform OSI research. Vendors connected to the NBS test gateways using the Accunet X.25 network – recently created to interconnect the London and Detroit-based demonstrations of Autofact ‘85. One gateway enabled participating vendors to test if their products conformed to X.25, token bus and CSMA/CD compliant implementations, as well as supportive applications: such as converting FTAM to ISO FTAM. A second gateway was essential for the support, and hopefully the cooperation, of the DoD. It translated TCP/IP and OSI protocols, at least as far as the constraints of both protocols allowed. Any Government agency and organization supporting OSINET could use these gateways.

Mulvenna, then responsible for OSINET, later described the organizations:

OSINET is an organization of vendors and users that use an X-25 network as the backbone to test and demonstrate OSI protocols. It arose out of the need, in 1984 and 1985, when the vendors were getting together in one place and saying: “There’s got to be a better way of at least running the interoperability testing of our products. Vendors are supporting and using OSINET because they want to be able to simulate the real live environment in which their products are going to be marketed….Vendors, who will be selling competing products in the marketplace, cooperating with each other, because they realize it is in their own best interest to do so.

OSINET consisted of three elements: the OSINET network, a steering committee to manage the network and all the OSINET projects, and a technical committee to carry out the technical work assigned by the steering committee. Into 1988, NBS chaired the steering committee, operated an information center, administered the testing, and provided assistance to Federal Government agencies wishing to join OSINET.

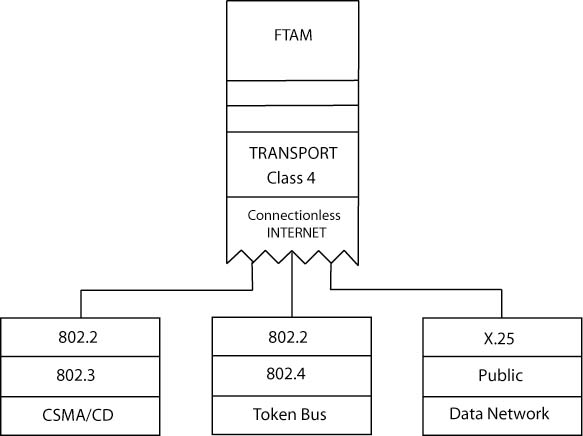

To administer conformance and interoperability testing, the NBS used the gateway prototyped during Autofact ’85. (See Exhibit 12.9 OSI Testing Gateway) A typical vendor conformance test required a vendor to pre-arrange with the NBS the tests it needed for its implementations. At the arranged time, the end user would connect to a testing gateway at NBS using the Accunet X.25 network. They then could test their implementations for OSI conformance. Tests included the first four layers of the ISO Model for X.25, token bus and CSMA/CD. ISO FTAM testing was separate. In this sense, the NBS served as the certifying organization for OSINET members for the first four layers of the ISO Model.

OSINET could also meet the need for vendor-to-vendor interoperability testing. Vendors first prearranged tests. Once they interconnected their products over OSINET, they could each run tests against the others’ implementations. Customers might also require all of its vendors to pass NBS tests of interoperability. These tests reduced, even minimized, much of risks of buying OSI implementations that might not interoperate with those from other vendors.

Exhibit 14.8.1 OSI Testing Gateway

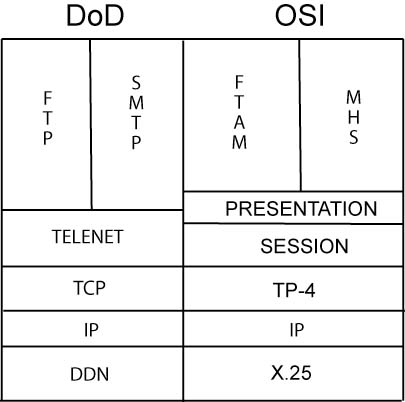

OSINET members also had access to a gateway the NBS had created for the DoD to convert TCP/IP protocols to those of OSI. (See Exhibit 12.10 OSI/DoD Gateway Protocol Suites) Mulvenna remembers:

We also have developed our application layer gateway here at NBS, which will transform the OSI protocols to the DOD protocols. It is to help the TCP/IP world move toward, and work with, the OSI world, to push them, gently, in the direction of OSI. The gateway will be available to both the DOD users and the OSI users on OSINET.

While conformance and interoperability testing, as well as TCP/IP-to-OSI conversion testing, was necessary, it was far from sufficient. An obvious barrier to market success was the growing installed base of TCP/IP implementations; i.e., a customer already successfully using TCP/IP products would be less likely to replace working software.34 Another problem could come from those customers wanting seven-Layer interoperability tests, not just the four-Layer tests developed and supported by the NBS. The NBS, however, had been clear that it was not going to perform similar roles for layers five through seven. It had enough to do, such as persuading the DoD to adopt OSI? To be responsible to the needs of vendors, the NBS created a non-profit organization, the Corporation for Open Systems (COS) to which it transferred non-exclusive rights of all its testing and gateway intellectual property and some of the related assets. COS would satisfy user needs for layers five to seven services. How quickly this could happen is reminiscent of 1979, when Congress finally trebled the budget for LAN and OSI standards. Only in 1985, the political climate was for government to shrink, not grow. Rosenthal opined in 1988:

Fundamental concept was NBS had all this test technology, and Reagan had a privatization mindset, and still does, so what better thing than to try to get COS out of it?

Exhibit 14.8.2 OSI/DoD Gateway Protocol Suites

COS would be the first of two initial recipients of the NBS testing tools and methodologies. Announced in the first quarter of 1986, the trade press warmly received the news.36 There were still questions, such as would IBM participate, but the prevailing reaction was positive. It would now be up to COS “to develop a consistent set of specifications, test methods and services for all OSI layers and application protocols.”37

All too quickly the initial optimism and hope turned to criticism. Some criticism was justified, such as COS turning down the tools already developed by Europeans; or maybe justified, such as frequently changing the rules of membership. Then there was the appearance of the NBS not having taken some of the problems seriously, such as those it had been trying to solve since 1982. For example, in June 1987, Data Communications Magazine reported that COS had selected TCP/IP for an internal network, not the equivalent OSI protocols. The reason, the computer vendor, SUN Microsystems, did not yet support OSI protocols. A COS researcher, Steve Smith is quoted in Data Communications as saying:

I realize it may look bad, but we do plan to migrate [to the OSI protocols].38

Meanwhile, procurement of computer and networking equipment by the agencies of the Federal Government had continued. The lack of OSI products, as well as the bewildering choices of OSI protocols, encouraged the purchase of proven TCP/IP products. The same factors that inspired the creation of the MAP and TOP Profiles now plagued government procurement. Customers (in this case the Federal Government) wanted to reduce complexity, increase compatibility, and buy products that they could use. After all, the purpose of Internetworking products was to make organizations more efficient and productive. Critical to user adoption, then, was overcoming the confusion that the development of Networking and Internetworking standards had left.

To solve many of these problems, in September 1986, NBS held the initial meeting of government agencies wanting to create a Government OSI Profile, or GOSIP. Representatives from 19 government organizations participated in the effort to “coordinate the acquisition and operation of OSI products by the Federal government.”39

Once GOSIP was specified, the plan was for it to become a FIPS. Heafner remembers:

When I first got here, the notion was: “Let’s write down all of these specifications and go publish them as soon as we can as FIPS.” Really, I stayed here until I felt my job was done, which was to write the initial GOSIP. That was all that was needed. We don’t need to write, and to republish and re-track and maintain the same standards that ANSI, ISO, CCITT and IEEE are doing. We simply need to write a procurement specification that references that work, and that’s what has been done with GOSIP.

The collaborations between federal agencies to produce GOSIP proceeded more harmoniously than Mulvenna anticipated:

It’s interesting that DOD was a major contributor to GOSIP. You would think that, of all the government agencies, they would have the most at stake in the status quo. That may be true for some of the people at the lower levels, but there has been a recognition by some of the higher people in DOD that OSI is the way to go.

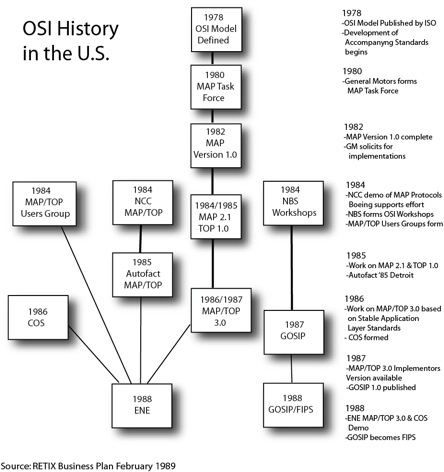

Mulvenna also noticed that the DoD agencies were “major contributors to the writing of the GOSIP document, major because they were more informed on the issues than perhaps some of the other government agencies, and they realized the services that the OSI protocols would provide them, because of their work with TCP/IP.” In other words, DoD officials did not take a combative approach to the choice between TCP/IP and OSI. Like many people experienced with Internetworking, they believed that researchers and standards bodies would find ways to make TCP/IP compatible with the more comprehensive capabilities that OSI promised. (See exhibit 12.11 OSI History in the U.S.)

Assistant Secretary of Defense Donald C. Latham, who in 1985 had endorsed the NRC’s report recommending the DoD migration from TCP/IP to OSI, confirmed Mulvenna’s interpretation in a July 1987 memo that:

these OSI protocols may be specified in addition to, in lieu of, or as an alternative option to DOD protocols […] They are designated as experimental because of the limited operational experience currently available with the OSI protocols, and the limited operational testing in a security environment concurrently defined in GOSIP. […] It is intended to adopt the OSI protocols as a full co-standard with the DOD protocols when GOSIP is formally approved as a Federal Information Processing Standard. Two years thereafter, the OSI protocols will become the sole mandatory interoperable protocol suite, however, a capability with inter-operation with DOD protocols will be provided for the expected life of systems supporting the DOD protocols.40

If they were disposed toward a more critical interpretation of OSI’s development, Latham, Mulvenna, and other officials in DoD and NBS might have noted that OSI in 1987 was more or less at the same experimental and commercially unavailable stage as it was in 1985. Nevertheless, the staunch support for OSI from the US Federal Government seemed likely to stimulate market development and, therefore, commercial success and user satisfaction.

Exhibit 14.8.3 OSI History in the U.S.

More encouraging signs were to come in 1988, including the formation of the International Public Sector Information Technology Group to coordinate GOSIPs published by Australia, Canada, Japan, Sweden, the United States, the United Kingdom, and West Germany.1 In August, the American government published GOSIP as Federal Information Processing Standards 146, Version 1, with the expectation that it would become a federal procurement requirement in August 1990. While FIPS 146 did not mandate that all federal systems migrate immediately or exclusively to OSI, Heafner, Mulvenna, and Rosenthal could at last congratulate themselves for a job well done. They had done their part. Now it was time for vendors to make products conforming with the OSI profiles MAP, TOP, and GOSIP.

- [33]:

Mulvenna remembers that OSINET: “Came along slowly because General Motors and others were promoting Autofact ‘85 at that time. In fact, all of our technical people were working on the IP Test System and refining the transport test system pre-Autofact ‘85.”

- [34]:

Stallings, William. “TCP/IP: Should You Feel Guilty? A Communications Conundrum”. Data Communications May 1988, p. 294.

- [35]:

Reproduced from a J. Mulvenna presentation handout.

- [36]:

Viewpoint, “Standards Group’s Strength Must Still Be Tested”. Data Communications, February 1986, p. 13.

- [37]:

“Implementing Open Systems Interconnection,” NBS Workshop for Implementors of Open Systems Interconnection, 1986, p.7

- [38]:

Dataletter, “For Own In-house Network, COS Selects TCP/IP,” Data Communications, June 1987, p. 15.

- [39]:

Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Energy, Education, Health and Human Services, Housing and Urban Development, Interior, Justice, Labor, Transportation, Treasury; the Environmental Protection Agency, General Services Administration, Library of Congress, NASA, National Communications System, National Science Foundation, and Office of Management and Budget. U.S. Government OSI User’s Committee, US Government Open Systems Interconnection Profile (GOSIP) Version 1.0, October 27, 1987.

- [40]:

Ibid.