Chapter 14 - Internetworking: Emergence 1985-1988

14.7 Autofact Trade Show - November 1985

The organizers of the OSI demonstration knew they needed to prove to the ‘world’ that OSI worked; that customers could now buy products to implement MAP, TOP and internetworking solutions. Such solutions were directed at large manufacturers wanting to achieve productivity gains comparable to those attained in their office systems. General Motors, for example, bought equipment from over 100 vendors but lacked standards: hence its substantial support of MAP.26 Customers (such as GM) that used a variety of information systems and networks would buy the next generation of internetworking products as long as it was clear that the ultimate goal of interoperability would be met. The OSI demonstration organizers felt both the pressure to make OSI launched and the weight of so much to do. There remained all the work left unfinished from NCC, the added complexity of integrating numerous interconnected networks, as well as the goal of substantially scaling up the sophistication of the demonstration. The good news was they would have their audience: the show drew a record 30,000 people with approximately 200 vendors exhibiting MAP-compatible and automation products.27

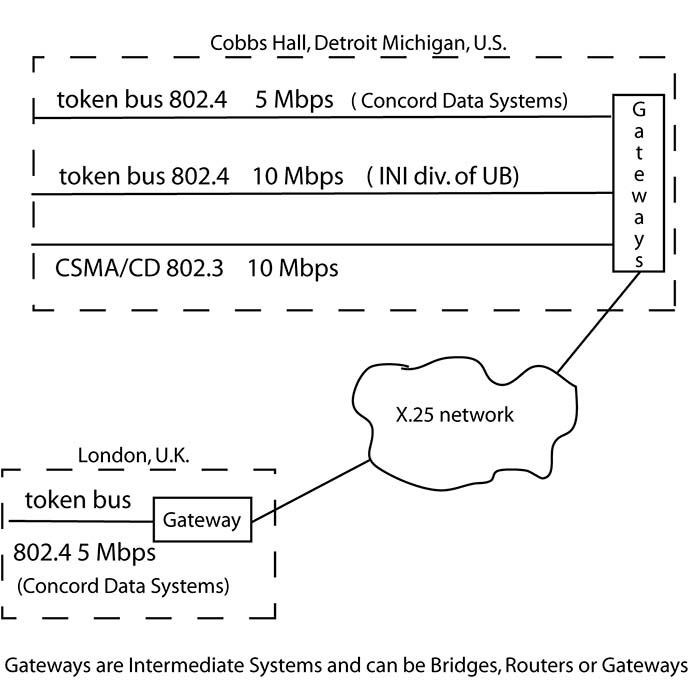

The OSI demonstration interconnected two locations: Detroit, MI and London, England. In Cobb Hall, Detroit, there were three LANS: two token bus LANs, one from Concord Data Systems and one from INI, and a CSMA/CD LAN. These three LANs supported MAP and TOP applications as if one integrated LAN. They, in turn, were connected to a X.25 public data network that connected them “seamlessly” to another 5 Mbps Concord Data Systems token bus LAN in London. (See Exhibit 12.7 Autofact ’85 OSI Demonstration Layout) In addition to data processing equipment such as computers and terminals, a variety of factory automation devices, including robots, vision systems and engineering workstations, let customers play three different applications: a custom designed version of the ancient game Towers of Hanoi, or Hot Potato or an interactive FTAM application.28 The twenty-one companies demonstrating equipment were able to communicate across all five interconnected networks.29

A later NBS publication would describe the demonstration as:

Using OSI protocols, Manufacturing Automation Protocol (MAP) and Technical and Office Protocol (TOP), the participating companies integrated a simulated small-scale factory operation, supported by office systems. The MAP systems, designed for the plant floor, and the TOP systems, designed for the engineering and office applications, were connected for information exchange.30

Exhibit 14.7.1 Autofact ’85 OSI Demonstration Layout

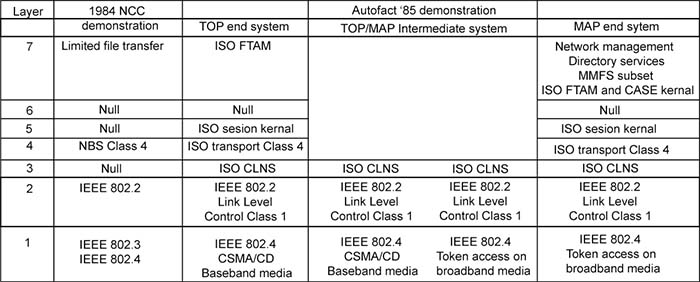

Bridges, Routers and Gateways, the Intermediate systems, interconnected the different networks. (See Exhibit 12.8 1984 NCC and Autofact ’85 OSI Implementations) In that Exhibit, a router is used to connect a MAP end system to a TOP end system; both use the connectionless Network and Transport Layer protocols. Gateways, needed to support Layer 7 applications, could convert from IBM, DEC, proprietary or TCP/IP file structures to ISO FTAM. As shown, the use of ISO FTAM, ISO transport Class 4 (the TCP-equivalent protocol) and ISO CLNS brought the state of networking close to the initial objectives set by the NBS, and much further along than the demonstration at NCC.

While well attended and considered a success (“GM’s MAP steals show at Autofact”31), even outsiders recognized demonstrations were different than working products for sale (“On the show floor, there are plenty of demonstrations but few available products”32). Again, the NBS and MAP/TOP organizers had work to do and, in the case of, the NBS work they did not want to do. To-date, the NBS had played a key role in converting the OSI “connectionless” protocols of the Network and Transport Layers to Intermediate Systems against which the vendors could test their implementations. Ensuring that incompatible computer-based systems could exchange information might be an appropriate responsibility for the NBS. Continuing to be responsible for creating test systems for the Upper Layers of the OSI Model, however, was beyond the mandate of the NBS. The NBS, not wanting to bail on the overall project, concluded it could help in four ways: continue to host the Implementors Workshops, finish the work required for a functioning OSINET, continue testing gateways/routers on OSINET, and spin the NBS testing tools and methodologies off into a new organization(s).

Exhibit 14.7.2 1984 NCC and Autofact 1985 OSI Implementations

The corporate organizers also had their “plates full,” so if everyone’s attention and time were to be maintained, they had no time to waste. The first meeting of the TOP user group convened in December 1985. In March 1986, the MAP user group released MAP 2.1. Among its improvements was support for the 10 Mbps token bus of INI, described as a backbone network.

- [26]:

Paulina Borsook, “Kaminski of GM: A mission for a swift factory standard,” Data Communications (March 1986), p. 109.

- [27]:

Korzenlowski, Pau, “GM’s MAP steals show at Autofact,” Computerworld (Nov. 11 1985), p.1

- [28]:

Kaminski, Michael A., “Autofact ’85: preview of new protocols in action,” IEEE Spectrum (April 1986), pp. 58-59

- [29]:

See: Mantelman, Lee. Newsfront, “MAP: GM and Boeing Promise a Real Four-Bus Circus,” Data Communications October 1985, pp. 78-79.

- [30]:

“Implementing Open Systems Interconnection,” NBS Workshop for Implementors of Open Systems Interconnection, Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology.

- [31]:

Korzenlowski, Pau, “GM’s MAP steals show at Autofact,” Computerworld Nov. 11, 1985, p.1

- [32]:

Ibid.