Chapter 08 - Networking: Diffusion 1972-1979

8.7 Ethernet and Robert Metcalfe and Xerox PARC 1971-1975

Last observed at the ICCC demonstration, an incredulous Metcalfe couldn’t believe the mocking laughter of the group of AT&T executives when the Arpanet momentarily failed. Metcalfe thought them insensitive to all the hard work and hopeful visions he and his colleagues shared - another example of the abusive, arbitrary behavior of those with authority and power. Admittedly his ire may have been easily provoked, for his world had been thrown into disarray by a felt injustice suffered just months earlier. To understand Metcalfe’s state of mind and how his unrelenting resolve set him on the course to invent the seminal local area networking technology of Ethernet requires us to return to the end of 1971.

When asked by Kahn to help with the organization of the ICCC, Metcalfe had every reason to feel he had earned his way into the inner circle of those giving birth to the Arpanet. So despite the fact that the first half of 1972 already loomed as too busy to contemplate – his PhD thesis had to be finished and defended in June and he had to find a job, one that would hopefully start in July – Metcalfe agreed to help. His uninformed decision two years earlier to focus on networking, and then to write his thesis on the Arpanet, now seemed uncannily prescient, as if some predestined momentum were sweeping him forward into a larger future.

Interviews confirmed his sense of being part of something important. Most opportunities smacked of bringing others up to speed, of transferring what he already knew and little appreciation for how much needed to be redone. The same could not be said for his interviews with Jerry Elkind and Robert Taylor, dual heads of the Computer Science Lab of Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). Elkind and Taylor, formerly of BBN and IPTO respectively, challenged him not simply to extend his Arpanet experiences, but to join a team dedicated to building a new paradigm of “office automation.” He liked everything he heard, including the Bay Area location, and agreed to start in July, after defending his PhD.

In the early spring, ICCC responsibilities took Metcalfe to Washington D. C. and, as usual, he stayed at the home of his good friend, Steve Crocker. After a customary late evening of spirited conversation, Metcalfe retired to his bed, the living room couch. Restless, he grabbed the 1970 Proceedings of the Fall Joint Computer Conference off the adjacent coffee table in hopes of reading himself to sleep, but his attention immediately focused on an article by Norm Abramson titled: The ALOHA System – Another alternative for computer communications. Metcalfe vividly remembers:

I’m reading this paper about how the ALOHAnet worked, statistically. The model Abramson used was infuriating to me. Infuriating, because it was based on a model that was tractable but inaccurate. In other words, you assume a bunch of things about a system that make the mathematics do-able, but the assumptions are highly questionable. So I’m reading Abramson’s work and it struck me the same way, which is: Assume that you have an infinite number of people sitting at keyboards, and they just type. No matter what happens they just keep typing. Even if they get no answer they just keep typing. Let’s see how the system performs. Well, when I read that, I said: ‘But people don’t. They DO stop typing! I mean if they don’t get an answer, they wait. This is not accurate.’ Now it was Poisson processes and exponential distributions and all that stuff that you can just math to death, and it all works out in a beautiful closed form formula. The trouble was, in my mind, that the ALOHA system was not being properly modeled. Mind you at the time, I was a graduate student dying to find some mathematics to put in my thesis.

In June, a confident Metcalfe presented his thesis to his Harvard professors:

It was rejected, and I was thrown out on my ass! But, imagine the scene - Here’s this graduate student who did all of his work at MIT, shows up to defend his thesis among a bunch of professors for whom he had carried no water for the preceding three years and they are asked to make a judgment on the intellectual content of my thesis. I got blown out of the water by them

Metcalfe’s thesis was rejected for not being sufficiently mathematical or theoretical. A stunned Metcalfe, doubting he could find the needed new, undiscovered, theoretical or mathematical content in Arpanet, decided he had to go to Hawaii and learn more about the ALOHAnet. Contacting Abramson, he received a gracious invitation. Then he had to convince his new employer to give him the needed time off.

On hearing Metcalfe’s disappointing news, PARC management couldn’t have been more supportive. Other than bringing PARC up on the Arpanet, their IMP would not be installed until October, Metcalfe was given the freedom to do what he needed to do to beef-up his thesis and satisfy his commitments to Kahn. Before leaving for Hawaii, Metcalfe, PARC’s new “networking guru,” received a briefing on the Data General Nova 800’s and the Multi-Processor Communications Adapter (MCA) that would interconnect them. The MCA was a 16-bit parallel cable connecting one machine to the next carrying data at 1.5 megabits per second.

In Hawaii, a serious minded Metcalfe focused on what he needed to learn and, other than playing a few games of tennis and tipping a few beers with two of Abramson’s graduate students, Charlie Bass and John Davidson, he worked and did little else. Abramson remembers: “We went out to dinner a couple of times, that kind of interaction, and he was rather closed-mouthed about what he was doing and I didn’t want to push him.”

To understand the ALOHAnet, Metcalfe began constructing mathematical models and comparing the results to actual data. He also modeled what would happen if people only typed when they got answers; and when they received no answer, they stopped and waited until they did – a condition known as blocking. Metcalfe remembers:

This had a dramatic effect on how your observed system would perform. And in the process of doing that modeling, it became obvious the system had some stability problems. That is, when it got full, it got a lot of retransmissions. That means if you overloaded it too much it would slip off the deep end. But in the process of modeling that with a finite population model, meaning people stop typing when they did not get an answer, I saw an obvious way to fix the stability problem.

I had studied some control theory at MIT and this was a control problem. That is, the more collisions you got, the less aggressive you should be about transmitting. You should calm down. And, in fact, the model I used was the Santa Monica freeway. It turns out that the throughput characteristics of freeway traffic are similar to that of an ALOHA system, which means that the throughput goes up with offered traffic to a certain point where you have congestion and then the throughput actually goes down with additional traffic, which is why you get traffic jams. The simple phenomenon is that, psychologically, people tend to go slower when they’re closer to the car in front of them so as the cars get closer and closer together and people slow down the throughput goes down, so they get closer and closer and the system degrades. So it was a really simple step to take the ALOHA network, and when you sent a message and you got a collision, you would just take that as evidence that the network was crowded. So, when you went to re transmit, you’d relax for a while, a random while, and then try again. If you got another collision you would say “Whoa, its REALLY crowded’, and you’d randomize and back off a little. So the ‘carrier sense’ expression meant ‘Is there anybody on there yet?’

Well, the ALOHA system didn’t do that, they just launched. So, therefore, a lot of the bandwidth was consumed in collisions that could have been avoided if you just checked. And collision detection was, while you’re transmitting, because of distance separations, its possible for two computers to check then decide to send and then send and then later discover that there was a collision. So, if while you were sending, you monitored your transmission, you could notice if there was a collision, at which point you would stop immediately. That tended to minimize the amount of bandwidth wasted on collisions.

Metcalfe did not yet realize that his seminal insight of collision detection would have important implications once back at PARC when confronted with interconnecting many computers. Metcalfe presented his findings at a University of Hawaii systems conference.

Returning to PARC, Metcalfe dove into the problems of interconnecting the PARC computers to the Arpanet and writing up the Scenarios for the upcoming ICCC show. When he finally surfaced for air in late October, both projects completed, PARC management challenged him to conceive and develop a communications network able to support the needs of many Altos computers and peripherals such as the also-being-developed laser printers. This “next generation” computing environment posed unprecedented communication requirements because of the use of bit-mapped graphics both as user interface and document output. Voluminous computer communications would be routine, not the exception as with Arpanet. If the required communications could not be reliably supported, PARC’s new vision of computing might prove to be just a dream.

Fortunately for Metcalfe, PARC management understood they were trying to create a new paradigm of computing and proprietary innovation could create competitive barriers-to-entry. They had no interest Metcalfe replicating work of others, encouraging him instead to view the problem with an unbiased perspective and engineer a best solution. For Metcalfe, management’s mandate impelled him to treat his growing intuition of computer communications not just as thesis-driven speculation, but an opportunity worth seizing. In short, a prepared and motivated individual had encountered inviting conditions.

Metcalfe fully understood the dynamic state of computer communications and scanned the literature for any relevant developments that might influence his work. On learning of Farber’s work at UCI, he obtained a copy of his February IEEE paper. (Metcalfe: “We became friendly arch rivals.”) He also contacted Cerf, an assistant professor now just ten minutes away at Stanford, and started attending his graduate seminar on networking; soon becoming an instructor. In early 1973, Metcalfe participated in the discussions Cerf and Kahn were having as to how to redesign the Arpanet NCP protocol.

On May 22, 1973, Metcalfe distributed a memo marked Xerox sensitive to the ALTO ALOHA team. The subject: Ether Acquisition.28 To quote from the cover page:

"Here is more rough stuff on the ALTO ALOHA network.

I propose we stop calling this thing "the ALTO ALOHA Network". First, because it should support any number of different kinds of station -- say, NOVA, PDP-11, ...... Second, because the organization is beginning to look very much more beautiful than the ALOHA radio network -- to use Charles's "beautiful".

Maybe: "The ETHER Network". Suggestions?

I hope to be simulating soon. Help? Inputs?

I hope you will not be offended by my attempts to make this thinking and design appear theoretical."

In the memo, Metcalfe discusses the ETHER Network:

"We plan to build a so-called broadcast computer communication network, not unlike the ALOHA System's radio network, but specifically for in-building minicomputer communications. We think in terms of NOVA's and ALTO's joined by coaxial cables.

While we may end up using coaxial cable trees to carry our broadcast transmissions, it seems wise to talk in terms of an ether, rather than 'the cable', for as long as possible. This will keep things general and who knows what other media will prove better than cable for a broadcast network; maybe radio or telephone circuits, or power wiring or frequency-multi-plexed CATV, or microwave environments, or even combinations thereof.

The essential feature of our medium -- the ether -- is that it carries transmissions, propagates bits to all stations. We are to investigate the applicability of ether networks."

Metcalfe explains the ether:

And what the ether was, the original ether was, was an omnipresent passive medium for the propagation of electromagnetic waves. It was going to be a medium for the propagation of electromagnetic waves, data packets, hence the cable is the ether. So it was an ether, and it was a network using an ether, so it was an Ether Net.

Metcalfe remembers encountering Leonard Kleinrock at Washington National Airport and showing him the mathematics in his PhD. thesis.

He told me it was: ‘Not very rigorous.’ He pooh-poohed it.

By May, Metcalfe had finished adding the mathematics of how the ALOHAnet worked to his thesis and re-submitted it to his new thesis advisor, Jeff Busen. This time it was accepted and Metcalfe received his PhD. in June 1973. Metcalfe notes ironically:

Indicative of how I got it – Harvard University did not publish my PhD. thesis. It was published by MIT, Project MAC, where I had done all the work. So it was the thesis finished at Xerox, for a Harvard PhD. thesis, published by MIT - Mac Technical Report #114.

In June, Metcalfe was given the go-ahead to build a prototype Ethernet.29 (Since Ethernet will become its known name, the convention will be to use it from the beginning.) Metcalfe remembers:

I needed to kind of get the project going; do the logic design, build the boards, write the microcode, etc. And I don’t like to work alone. In fact, I believe the ideal operating unit is two people. Three is too many and one isn’t enough. Two is perfect. So I went out looking for somebody to work with me, and one day, I saw this guy in moccasins with a ponytail down to his back padding his way through Building 34 at PARC. And he didn’t look busy. He looked like he didn’t have enough to do. So, I checked into it and it turned out he was a graduate student from Stanford who was working for David Liddle. So I asked David about him and David said: ‘Well, why don’t you get him to work on your project with you?’ So I approached David R. Boggs and propositioned him and we entered into a two year long project together.

The Ethernet project required fleshing out Metcalfe’s preliminary design, building the hardware to attach the computers to the connecting coaxial cable, and designing and coding the networking protocol so computers and peripherals could share information. Metcalfe realized that he needed a more streamlined communications protocol than the NCP of Arpanet or the new protocol being designed by Cerf and Kahn that had to function over may different kinds of networks.

By year-end 1973, as Metcalfe and Boggs progressed from design to implementation, Metcalfe found he had little time to participate in the Cerf-led sessions. He had real project deadlines to meet that required making choices and reducing those choices to hardware and software. Further constraining Metcalfe’s relationship with Cerf was Xerox’s confidentiality requirements that restricted what Metcalfe could disclose to Cerf and his colleagues. Without being able to openly discuss his work, Metcalfe derived little benefit from the more academic and open-ended discussions being moderated by Cerf. Cerf acting under the aegis of DARPA sought to bring about a standard from within a very diverse community having little motivation to cooperate or resolve issues in a fixed time frame. Consequently, the early development of local area networking protocols being pioneered by Metcalfe and Boggs proceeded down a very different path than Cerf’s and Kahn’s redoing of NCP, a digression that would soon become important.

Metcalfe’s design objective for Ethernet was a communication system that could “grow smoothly to accommodate several buildings full of personal computers and facilities needed for their support.”30 (Exhibit 6.4 Ethernet) Two secondary, yet desirable, objectives were that it had to be inexpensive and, preferably, distribute control to eliminate the “bottleneck”31 inherent in centralized control. Metcalfe’s design incorporated architectural contributions from Arpanet and ALOHAnet: packet-based communications with broadcast transmission. Beginning with “the basic idea of packet collision and retransmission developed in the ALOHA Network,”32 Metcalfe added his collision detection insight. Computers or peripherals would constantly listen to the communication channel (the “Ether”) and only send – broadcast – their messages when they detected a clear channel. If collisions with packets being sent by other stations were detected, all sending stations would stop transmitting, wait intervals of time in proportion to the frequency of collisions, and retransmit. If collisions occurred again, the transmitting computers would wait a longer interval and retry; repeating the process until successful. What makes Ethernet possible is most messages are short, hundreds or thousands of bits, compared to the communication channel bandwidth of 3 megabits per second - the very same principle recognized a decade earlier by Baran and Davies.

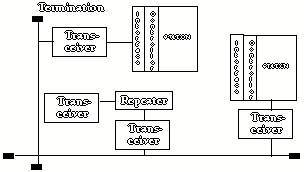

The final design of the Ethernet network proved elegantly simple: some hardware to interconnect computers and peripherals so they could exchange bits and a networking protocol to make sense of the bits. The hardware consists of interface controllers, transceivers and taps, and a transmission media. An interface controller, or adaptor, connects to the backplane, or bus, of computer equipment (Ethernet stations) and sends and receives formatted data to the transceiver. The transceiver converts the digital data coming from or going to an interface controller to analog signals required by the transmission media (communication facility). In effect, the transceiver acts like a modem. Taps are needed to physically connect transceivers to the transmission media with minimal disruption during connecting or disconnecting.33 And finally, there is the transmission media needed to transport the signals. The first transmission media was coaxial cable, initially with its famous yellow sheathing. To interconnect two or more Ethernets, an additional piece of equipment, a repeater, is needed.

Exhibit 8.7.1 Ethernet

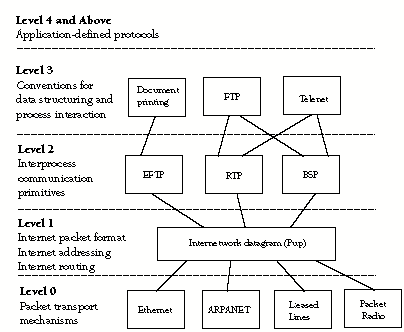

The networking protocol is implemented in software to execute in both the Etherent stations and the interface controllers and provides the essential services of “error correction, flow control, process naming, security and accounting.”34 The networking protocol Metcalfe and Boggs created – PARC Universal Packet, or Pup – leveraged the knowledge and experience gained from ARPA’ s creation of NCP and its recreation being led by Cerf and Kahn. Pup was in fact a hierarchy of protocols that enabled end-to-end functionality, including file transfer and email.35 (See Exhibit 6.5 Pup Protocol)

By late 1974, Metcalfe and Boggs had a 3 megabit per second Ethernet with Pup working. Once successful, Xerox filed for patents covering the Ethernet technology under the names of Metcalfe, Boggs, Butler Lampson and Chuck Thacker. (Metcalfe insisted Lampson, the “intellectual guru under whom we all had the privilege to work” and Thacker “the guy who designed the Altos” names were on the patent.) Once the patent had been filed, Metcalfe and Boggs could publish their work, submitting a paper to the Communications of the ACM titled: Ethernet: Distributed Packet Switching for Local Computer Networks. Published in July 1976, it became a seminal paper for all work on local area networks to follow. By mid-1975, PARC had installed a one hundred node Ethernet network that was robust by 1976.

Exhibit 8.7.2 The Pup Protocol

- [28]:

The use of the word Ether is homage to Michaelson and Morley whose experiments provided the first strong evidence against the theory of a luminiferous ether.

- [29]:

Kahn opines on Metcalfe’s conceiving Ethernet: “Bob was super smart commercially, you know, to understand how to make something work simply and effectivly. That was the brilliance. It was engineering coup.”

- [30]:

Metcalfe and Boggs, “Ethernet: Distributed Packet Switching for Local Computer Networks,” Communications of the ACM, July 1976

- [31]:

Ibid.

- [32]:

Ibid.

- [33]:

In a typical example of collaborative research, such as Ethernet, Liddle, who had worked for a cable TV company while in school, proposed the use of passive taps as used in cable TV, a technology outside the purview of Metcalfe and a technology that worked just fine at first.

- [34]:

Metcalfe and Boggs, “Ethernet: Distributed Packet Switching for Local Computer Networks,” Communications of the ACM, July 1976

- [35]:

David R. Boggs, John F. Shoch, Edward A. Taft, and Robert M. Metcalfe, “Pup: An Internetwork Architecture,” IEEE Transactions on Communications, Vol. Com-28, No. 4, April 1980, pp.612-624.