Chapter 14 - Internetworking: Emergence 1985-1988

14.12 Codex

Codex entered 1987 with a new President and an impressive new headquarters. In the spring of 1986, John Lockitt was promoted from within to be President and Chief Executive Officer, ending the run of founder Presidents. Then in September, Codex completed its move into a new, upscale New England red brick, 250 thousand square foot headquarters on a 44-acre site in Canton, MA, referred to as “The Farm,” as it once proudly was. At the close of its 1986 fiscal year, Codex retained claim as the largest company in Computer Communications. Then in early 1987, Codex finished its radical Five Year Strategic Plan by redefining its historical “Fancy Box” strategy, yet without coming to terms with its recent failures of execution.

Under other circumstances Lockittt might even have seemed a perfect choice for President: an engineer and senior vice-president for wide-area network operations. Lockitt had led the development of a successful 6740 statistical multiplexer project, yet it was also under his leadership that Codex failed to develop a T-1 multiplexer. Nevertheless, Motorola executives had suddenly concluded Storey was not forthcoming in disclosing all the costs of developing the Farm and they let him go. Why Storey let himself become so distracted, even confused, with the Farm project is poorly understood, but his desire to create an architectural masterpiece came at an unfortunate time, a fact he as CEO should have known. Not that total costs are ever found on accounting ledgers, for Storey let personal reasons crowd out important corporate duties, and the time he spent on architectural issues was exactly opposite the laser focus of entrepreneurs with venture capitalists oversight who were working tirelessly to create the competition they hoped would dethrone Codex. Companies that would attain market values of hundreds of millions of dollars, creating more capital than the costs of many Farms. Such was the doubtful state-of-affairs Lockett assumed in the spring of 1986; an engineer who was about to have twelve direct senior reports, more than the number of engineers he had been managing. Reflecting the bureaucratic disarray that had become Codex, only three of his new reports were accountable for product development and marketing, i.e. sales and future products.

Art Carr, President before Storey, and at the time of this interview in April 1988, leading a venture capital start-up, expressed his concern:

Codex, as a strategy, evolved from a product company, to a subsystem company, to a network solution company where they’re at now. The problem now is that they don’t have enough home grown components of that strategy. It seems to me, from a distance, that Codex has got an excellent strategy, financially, but the engineering organization, which in the dawning of my experience there in 1968 was the biggest engine in the world, is now the weakest link in implementing the strategy.

The electrical engineers and information theorists in Carr’s Codex knew how to modulate and demodulate the waveforms of electrical signals traveling over copper wires into square waves interpreted as bits. They did what even AT&T said could not be done, build a 9600 bps modem.61 The speed had since more than doubled to 19,200 bps, and although Codex had become complacent and briefly lost their role as leader, they had recovered and were again the acknowledged market leader. Modem technology and standards exist in the Physical Layer, or bottom Layer, of the OSI Model. The leading edge of computer communications in 1987 was the domain of computer scientists and network theorists who were pushing the frontier of the Network Layer, the Layer in the OSI Model for interconnecting many networks. These products were called gateways and routers, not modems: products that Codex did not have nor knew how to build.62

All too frequently, when a company relocates to a newer, larger headquarters, it is marketed as positive. Only too often the move contains the seeds of an ominous future. To traverse the long driveway, across rhythmic green grass pastures and scenically landscaped ponds, up to the stunning headquarters of Codex, worthy of Architectural Digest, did not need to be explained, for even the eye of a novice would read the signs of a successful company, not a hungry one fighting for its life. No, it looked as expensive as it was. Symbolically, to call on engineers was a drive across town to far less impressive facilities.

In 1986, Codex recorded revenue of $389 million. Profits were flat with 1985 as Codex continued to bury the costs of its new headquarters and two technological defeats, instead of enjoying the profits of accustomed technological domination and success. Nevertheless, Codex remained the largest Computer Communication company. For the years 1982-1986, Codex reported an impressive compounded annual growth rate of 18.8%, including the minimal 8% of 1986.63

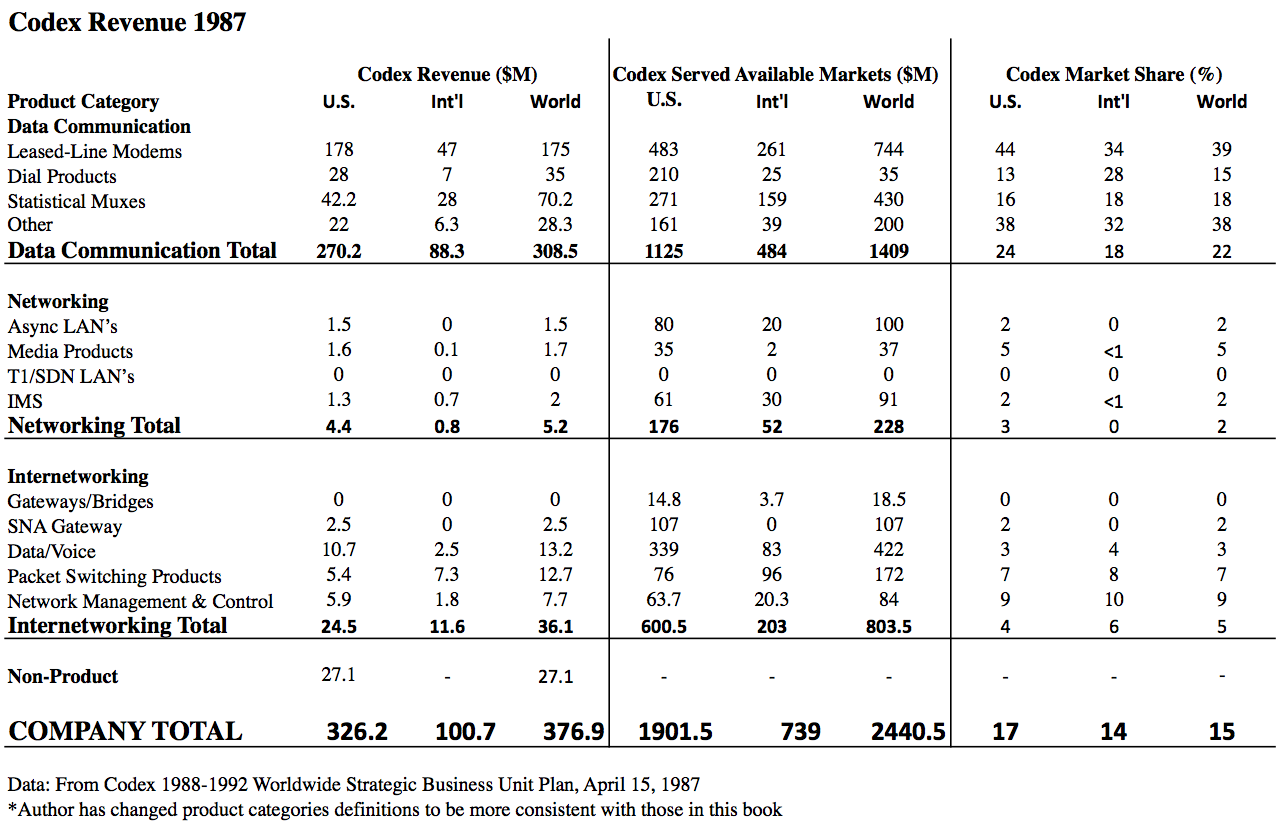

The company still organized its product accounting as in the past, into three Product Market Segments: Transmission, Wide Area Networking and Local Area Networking. (See Exhibit 12.13 Codex Revenue 1987) Theses categories are similar to those of this book: Data Communications, Networking and Internetworking. The most significant adjustment to better align the two reporting conventions requires moving Statistical Muxes to Data Communications, out of Wide Area Networking.64 Using the U.S. data from Exhibit 12.13 Codex Forecasted Revenue 1987, as proxy for 1986 reveals Codex is still predominantly a lease-line modem company (54.6%) and conclusively a Data Communications company (82.8%).65 Its domestic share of the lease-line modem market was 44%. Having innovated the 9600 bps lease-line modem in 1968 endowed Codex with a lasting market advantage. However, this advantage had not helped Codex enter either the LAN or T-1 multiplexer markets.

Exhibit 14.12.1 Codex Forecasted Revenue 1987

One of the most important tools available for Lockitt to stamp his imprint on the future of Codex was to oversee and approve the Five Year Financial Plan. Completed in early 1987, the focus clearly communicated the rationale for the shift to a more “sophisticated” product marketing strategy than Fancy Boxes, to a business school inspired model of segmented markets, each with their own distinctive make-up. The quadrant labeled Integrated Communications Networks are high-end products sold as network solutions; the market Codex was targeting. The Plan, however, reads less like a recipe for success than a buffet of poorly understood courses. Not to find fault, but to view through the lens of the surrounding history, Lockitt begins his opening Narrative with a minimal acknowledgment of their failures:

Codex did not keep pace with the strong growth in the T1 multiplexer market… Codex has also failed to capitalize on the rapid growth in the LAN and X.25 markets.

Locket ends by summarizing his vision as:

Our long range strategic intent is to exploit each technology in combination with other technologies and to provide optimum solutions for the customer rather than being wedded to a single technology.

As for T-1, the Plan masks the strategy of soon selling an OEM product, one from Stratacom that will replace the one from Avanti, for the short term, that is until they hope to design it out:

Launch T1 Nodal processor, a network backbone product and required core capability. Maintain significant advanced development efforts early in the planning period that will result in a new generation of T1 circuit/packet switched nodes in the mid-term.

And as for laying bare the opportunity found in the hottest market then emerging?

Gateways/Bridges: Invest to provide for homogeneous LANs with agile bandwidth allocation for T1 and STDM.

Codex seems to come down on the side of OSI, although it never joined COS:

OSI continues to gain momentum, with both DEC and IBM demonstrating intent toward compatibility with the standard. Industry spawned standards such as MAP and TOP will gain wider acceptance.

The Five Year Financial Plan is the blueprint to guide the actions and decisions of Codex management who embrace the goal of building a $1.1 billion company in 1992.

Carr opines in his interview with the author, around the time that this Plan was being distributed, and not addressing the Plan itself, he said:

I want to emphasize, I can’t tell you that if I were running Codex that it would have been different, but what happened was, we got a late start on LANs. That was during my time, and we got basically a no start. I don’t think we saw the significance of T1. We didn’t see the tariff changes, the significance of it. When we did, we bought product from Avanti, and again, it was a la the old Micom days. The theory was, buy from Avanti and design them out. The first step was, they were going to enhance Avanti, going beyond Avanti’s design, and then design them out. The same thing had been true in a number of other things since then. What’s happening, in my judgment, seeing from the outside, and I don’t know the details, Codex is depending entirely too much on buy-out product, as opposed to what it’s doing inside, and they’ve got a monumental organization down here in Canton that isn’t turning out the product.

Why was selling internally developed products so important? Profits, or more precisely gross margins. Buy-out products are lucky to command a 40% gross margin whereas internally developed ones should earn gross margins of at least 60%. That difference in profits earned, 50%, can mean success and failure: it is extremely difficult to finance product development on the lower gross margins of buy-out products.66

Before the end of 1988, two announcements seem to undermine Codex’s Five-Year Plan. On July 25, 1988, Network World ran a front-page article titled: “Struggling Codex trims work force.”67 Not the banner of a prosperous business behemoth. It reads that 250 employees out of a work force of 4,500 were laid off, a 6% reduction. Continuing it states that Codex probably “overestimated” sales of T-1 multiplexers. It would seem the deal with Stratacom had failed, just as the earlier LAN agreement with Ungermann-Bass had failed.

Then in December, Codex announced a 30% price reduction for its modems, forced to do so by IBM’s pricing.68

Competition was forcing changes even more drastic than lower product prices or reduced headcount: that same December 1988, Codex announced that it was putting its headquarters up for sale.69

- [61]:

See Chapter 3

- [62]:

A reviewer is quick to point out that a stat mux can be seen as a router with a much smaller packet size.

- [63]:

Codex 1988-1992 Worldwide Strategic Business Unit Plan, April 15, 1987 and The Five-Year Financial Forecast. The private data of Codex is excerpted from these two documents that were given to the author in 1987 in conjunction with investment banking services he was rendering for the company. Since it has been over twenty-five years, and Codex no longer exists as an entity, the author has not requested a formal release for use of these documents from Motorola. He has, however, made use of the data as if it were 1987-1988.

- [64]:

The Product Market Segment data is for the forecasted year 1987, not actuals for 1986 or earlier. Hence there can be some inconsistencies between the actual data of 1986 and/or forecasted data of 1987.

- [65]:

The only data the author has for this analysis.

- [66]:

Fifty percent is calculated: (60%-40%)/40%=50%

- [67]:

“Struggling Codex trims work force,” Network World, July 25, 1988. Pp. 1 and 4

- [68]:

“Codex marks down its modems by 30%,” Network World, December 12, 1988, ppgs/ 8 and 10

- [69]:

Boston Globe, January 1, 1989