Chapter 2 - Background

2.24 The Minicomputer -- 1959-1979

Worldwide revenues of minicomputers would total $2.5 billion in 1977, up from$835 million in 1973, projected International Data Corporation, a leading market research firm in 1974. “Nearly all ten major firms are profitable and, although price-cutting will continue, component costs will drop, enabling most to maintain their 20% before-tax profit margins.”185 This stands in sharp contrast to mainframe computers, which had just one consistently profitable firm, IBM, and only five other firms offering token competition. IBM so disregarded minicomputers it would not be until 1976 before they introduced one.

Just as IBM dominated mainframe computers, so would Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) come to dominate minicomputers – despite ninety-two companies introducing minicomputers between 1968 and 1972. By the early 1980’s, DEC would challenge IBM for market leadership before the two of them became prey to the personal computer.

The genesis of DEC returns us to the very same MIT Lincoln Labs responsible for the SAGE project (1950-1952). One of the 400 engineers hired to staff SAGE was Kenneth H. Olsen, then a graduate student studying for his masters degree in engineering at MIT. Olsen quickly excelled, displaying both initiative and leadership. When a team leader was needed to build a computer to test Forrester’s core memory, Olsen was chosen. Told he had nine months – Forrester didn’t believe it could be done in a year – Olsen’s team of fifteen engineers delivered the Memory Test Computer, or MTC, within nine months.

Olsen thrived within the culture of Lincoln Labs that encouraged and rewarded creativity and competence. Lincoln Labs’ very nature was to take technology risks – calculated ones – but ones leading to radical, not just incremental, innovations. Pushing the envelope, as it would later be called, the unique relationship that existed between Lincoln Labs and MIT’s engineering graduate programs energized both as they strove to better understand the information technologies and their use. The implications will be present through out this book.

Then in 1953, Olsen was thrust into an experience of a very different kind: one he would never forget, and one that deeply influenced the way he managed DEC into the success it was. Forrester needed a liason to IBM, someone to be in daily contact, to make sure the relationship between Lincoln Labs and IBM went smoothly. He selected Olsen.

IBM was the antithesis of Lincoln Labs. In 1952, IBM knew little about building vacuum tube computers. The principal reason IBM sought the SAGE project was to educate itself on how to build and manufacture computers. Little wonder IBM forced so many meetings, and there were so many levels of management involved in the most simple decisions. IBM was hiring hundreds of new employees, thousands including those in manufacturing, while undertaking the most complicated and complex project in its company history. IBM behaved so as not to fail – the exact opposite of the aggressively experimental culture of Lincoln Labs. “It was like going to a communist state,” Olsen remembers.186

During Olsen’s thirteen months in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., Norman Taylor, his boss, spent weeks at a time working with him. In their many off-hours together, Taylor suffered much of Olsen’s unhappiness. He tried to console him, but with little success. In late 1953, Talyor remembers a frustrated Olsen telling him: “Norm, I can beat these guys at their own game.”187 If IBM could succeed with their bureaucratic organization, just think how one with the freedoms and openness of Lincoln Labs would fare. Olsen’s belief and confidence in people seemed almost threatened – he began thinking more as a leader, an entrepreneur, than as simply an engineer.188

On returning to Lincoln Labs, Olsen assumed responsibility for a sub-group in advanced engineering. Soon he and Wes Clark proposed building an advanced computer using vacuum tubes. The idea was rejected – any advanced design should be made with transistors – this was Lincoln Labs not IBM. Had conservatism rubbed off? Olsen and his team immediately began developing transistor circuits to learn as much as they could. Soon they proposed building a computer with roughly the same architecture, but using transistors. Their plan approved, they set out to create what would become the TX-2 computer189 – to many the first personal computer and the beginning of a new computer trajectory.190 (That meant that all three computer trajectories began in the same laboratory at the same time. The TX-2 computer led directly to the LINC computers and the trajectory of personal computers, while the circuitry of the TX-2 was used in the PDP-1 computer, influencing the first minicomputer, the PDP-8 in 1965, and therefore the minicomputer trajectory. Concurrently, the SAGE computer was being designed and built which led to the IBM 704 and eventually to the System/360 – the mainframe computer trajectory.)

By 1957, Olsen felt ready to start a computer company. In August, Olsen, 31 years old, and Harlan Anderson, 28 years old, a friend and team member from Lincoln Labs, formed DEC with a $70,000 investment from the venture capital firm, American Research & Development (ARD). Post financing, ARD owned 70% of DEC, Olsen 12% and Andersen 8%. The balance, or 10%, was reserved to recruit a third partner, one talented in business management and marketing. (One never was hired.) DEC’s market value was therefore $100,000. General Georges Doriot, the legendary venture capitalist who helped found 150 companies, counseled the two aspiring entrepreneurs before their presentation to ARD’s Board of Directors: “First, don’t use the word computer. Fortunemagazine says giants like RCA and General Electric are losing money in computers. The board will never believe two young engineers, barely off campus, can succeed where others more experienced are failing.”191 They followed his advice and described the machines they wanted to build as printed circuit modules, not computers.

But they had started DEC to build computers. So in order to stay below the radar, to remain undetected, not to provoke reaction from existing computer firms, they named their first computer, the Programmed Data Processor, or PDP-1.192 Introduced in 1959, the PDP-1 was an 18-bit system, like the TX-2, and sold for $120,000. It could be used as front-end personal computers to the large scientific computers like STRETCH and LARC.193 Important circuits of the PDP-1 were the same as the TX-2. This could have become a problem, appropriating Government intellectual property without compensation, but Tayor intervened, advising MIT to do nothing. “If the guy wants to borrow this circuitry, what the hell?” Taylor argued.”He designed half of it.”194

The inter-relationship of DEC and MIT, especially MIT Lincoln Labs, was profound. In many respects, there existed little difference between them. To the engineers, working at DEC was essentially the same as working at the Labs, except for compensation, opportunity and, hopefully, job security. They all feared the expected day when Government R & D funding would dry up – and always for reasons they had little power to influence. DEC and Lincoln Labs shared much the same culture and missions because of people – with no one more important to DEC than C. Gordon Bell. Bell started working at DEC in June 1960. Well into the 1980’s, he was involved in designing all of DEC’s most important computers and crafted the DEC strategy that unseated IBM’s control of corporate computing. After Olsen, Bell looms largest in the success and history of DEC.195

DEC’s efforts to become a computer company seemed headed for failure until in 1962, International Telephone and Telegraph ordered fifteen PDP-1s to use in one of their telephone switching systems.196 This made ITT an OEM, the only customer type the first minicomputer companies had as they struggled for sales. Original equipment manufacturers – OEMs – embedded computers into their products – medical equipment, scientific instrumentation, or process control equipment – before selling the combination as finished product to end users. The computer had to be fast, that is it had to be real-time, dedicated in most cases to only one function and inexpensive. Small surprise the mainframe computer companies showed little interest. Minicomputers seemed truly a different business, as had computers to the manufacturers of tabulating equipment.

But minicomputer firms wanted to be more than simply OEM suppliers. They dreamed of selling their computers to large end user organizations – those wanting to extend the benefits of computerization throughout their organizations – or to organizations too small to justify a mainframe. To large corporations, the costs of minicomputers could often be justified solely from the savings in telecommunications costs. And as for the cost advantages of minicomputers over mainframe computers: in 1968, Hewlett-Packard Co. introduced a minicomputer that supported time-sharing for up to sixteen users for $89,500. The cheapest timesharing system sold by GE at the time was $527,000, six times as much.197

DEC also eyed timesharing. After designing four more computers, only two of which were introduced, in 1964, DEC announced the PDP-6 – carrying a price tag of $300,000. Despite early optimism, only twenty-three of them were ever sold – making it DEC’s worse selling computer ever. Even more worrisome, DEC’s revenues were up only 10% to $11 million in 1964. Profits, premised on higher sales, dropped from $1.2 million to $900,000. Olsen knew something needed fixing but what?

Olsen increasingly suspected the existing hierarchical organizational structure combined with an engineering dominated culture as the causes of DEC’s problems. There were always ways a product could be improved, or new features added, or excuses of too little time available as engineers labored to fix something old (especially old as already in production). The very organizational culture and structure engineers found so attractive, confused orderly, profitable operations.198 He needed to change the culture and structure – to invent a new DEC management style – one conducive to success, not impeding progress as now.

Olsen sought counsel from his two most influential advisors, Forrester, now a Board member, and Doriot, his investor. He received conflicting advice. Then it came to him – assign one executive responsibility for each product line. Each would act as an entrepreneur, with full profit and loss responsibility. They would shepherd product from development through profitable operations. It would become known as a “matrix” organization and is credited for much of DEC’s success.199 The enthusiasm, creativity and productivity that had marked DEC’s earliest days, and lighted Olsen’s vision, came to life. The effect was immediate and pronounced. Within two years DEC went public with a market capitalization of $77 million – 770 times its founding valuation.

The engine propelling DEC’s sales and profit growth during this period, the PDP-8, was introduced in the fall of 1965. It, more than any other computer, is considered the first true minicomputer. It had a 12-bit architecture and was designed by Bell and implemented by Edson deCastro. It sold for $18,000 and could fit on a desktop or laboratory bench. No one anticipated selling anywhere near the 50,000 they did. It proved a market for computers other than mainframe computers really existed and contributed to the explosion of minicomputer entrants beginning in 1968.

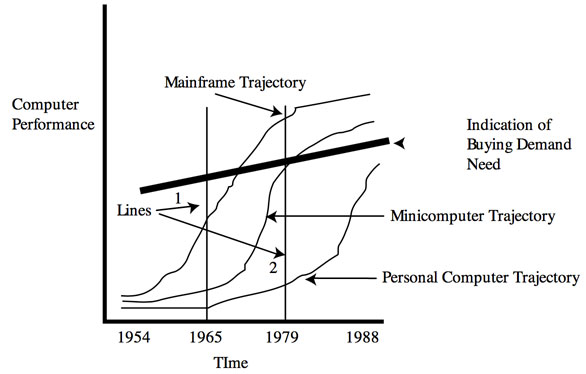

Even so, mainframe computer companies gave DEC and minicomputers hardly a look. They were locked into battle for survival with IBM and its System/360. But why did IBM not innovate the minicomputer? It certainly wasn’t from a lack of resources – DEC funding was only $70,000. This phenomenon of existing firms innovating a technology that should have given them the awareness and understanding to see new instantiations of the technology – such as mainframe computer manufacturers seeing minicomputers and being first and best to market them – is so common, an explanation is appropriate. See Graph 1.2 - Technology Trajectories and Buying Demand.

Exhibit 2.25 Technology Trajectories and Buying Demand

From the 1965 perspective of a mainframe computer company, minicomputers were not even competition. Minicomputers were never encountered in selling situations, and mainframes rented for $20,000 a month. The PDP-8 cost $18,000. But advances in semiconductor technologies, Medium Scale Integration (MSI) to Large Scale Integration (LSI) to Very Scale Integration (VLSI)200 , and software and peripherals, such as Winchester Disk Drives, all allowed more computing resources to be sold as the DEC VAX-11/780 minicomputer in 1979 than existed in the IBM System/360 mainframe in 1965. And by 1988, personal computers represented an alternative to both mainframes and minicomputers.201

In 1967, DEC knew it needed to begin designing their next generation minicomputer – the successor to the PDP-8. One decision had already been made for them, however. The architecture would be 16-bits, two 8-bit bytes. Even though DEC had never innovated a computer built on an 8-bit byte, the PDP-8 being a 12-bit computer, their new, PDP-X would be 16-bits. This standardization of technology had been dictated by IBM when they built the System/360 with an 8-bit byte. To co-join the learning curve advances that would accrue from IBM’s purchasing power, and the tide of innovation that would be attendent to it, meant converting to the 8-bit byte. (An excellent example of a relationship between market-structure and technological outcome.)

PDP-X would be the first computer since the PDP-1 to be designed by someone other than Bell, who in late 1966 had left DEC to teach at Carnegie-Mellon University. De Castro, promoted to design leader, presented the PDP-X design to management in late 1967. The recommendation echoed many of the same themes as had the presentation of IBM’s task force six years earlier, whose recommendations led to the System/360:

- A series of compatible products to replace DEC’s incompatible products. Products representing 85 % of the minicomputer market.

- A path of upgrade for customers to leverage their past investment.

- Conversion to the newest semiconductor technology (MSI), and

- Shared use of all software and peripherals.202

The product line managers, who under the new matrix organizational structure saw their roles being diminished, and senior management, who thought the concept too risky, rejected the PDP-X recommendations.

To de Castro, who harbored entrepreneurial desires, the decison to kill PDP-X gave him all the reason he needed to begin planning his new company. On April, 15, 1968, de Castro, Henry Burkhardt and Dick Sogge resigned from DEC to start Data General Corporation (DG). Their first product, the 16-bit Nova, was introduced in 1969. DG immediately became DEC’s most serious and emotionally-igniting competitor – many in DEC management, including Olsen, could never forgive de Castro and his team for leaving.203

Bell writes later, from the distance of 1984: “DG had a simple-to-build, yet modern, 16-bit minicomputer based on integrated circuits that enabled it to be priced below all existing products despite its late entrance into the market. In fact, the late entry was a benefit, since more modern parts could be used and the experience of others could be taken into account. The simplicity of the DG product allowed rapid distribution, especially to OEMs.”204 205

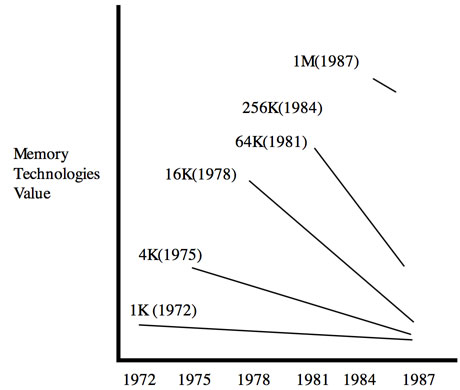

The issue of when product definition, final architecture and components, is fixed looms large because of the differing rates of innovation of all the technologies embedded in the product and on which it is dependent. An obvious component decision was when to lock-in the choice of memory. In semiconductor memory technology, however, the pace of change from one thousand bits (1K) of memory (1972) to one million bits (1M) of memory (1987) was phenomenal. Depending on which year a computer design was finalized determined which memory technology was used. Even a year later, memory with four times the capacity might become available. The following Graph 1.3 - Memory Trajectories is an effort to capture both the nature of discontinuous and of rapid change.

Exhibit 2.26 Memory Trajectories206

After the defection of the DG founders in April 1968, Olsen promoted Nick Mazzarese to lead the PDP-X effort. For another year and a half they struggled to complete a 16-bit design. By December 1969, Massarese desperate for help, arranged a meeting with Bell in Pittsburg. Along with roughly twelve other critical personnel, they presented the architecture and component technologies of PDP-X. When Bell and fellow professor, William Wulf, were asked their opinion, both agreed – they didn’t like it.207

What did they do? This dozen or so information technologists, under the architecural leadership of Bell, influenced by the intellectual work of one of his graduate students, Harold MacFarland, worked one very long weekend to design the PDP-11 – the most successful 16-bit computer.208 The DEC engineers had now been working on this objective for more than two years.Bell remembers the PDP-11 as “just good enough to beat Data General’s Nova.”“209

Only weeks later, on January 5, 1970, DEC announced the PDP-11, knowing it was still just a design. Sales price: $10,800. Over 250,000 PDP-11s were sold to make it the most successful 16-bit minicomputer – and designed in a weekend.

Reasserting technological leadership was critical to DEC, for between 1968 and 1972, ninety-two potential competitors entered the market. The most important were DG, HP, Prime, and finally IBM. A number of converging dynamics put the future up for grabs, including:

-

Integrated circuits:A rapidly changing technology trajectory from MSI (late 60’s) to LSI (mid-1970’s) to VLSI (early 1980’s). The levels of performance improvements – function up and costs down – were in orders of magnitude.210

-

Economics of timesharing - The prohibitive costs of using the telephone system drove the economics in favor of the rapidly improving minicomputer. “The intelligent little machines are just going to proliferate like mad,”said one executive.211

-

Minicomputer technologies - Not just integrated circuit componentry was improving, so were storage, operating systems, database systems, communications, and more. A Datamation article in 1971 reads:”Minicomputer prices are expected to continue to drop in the next three to five years at a rate on the order of 20% per year as they have for the last five years.”212

-

Capital Availability - The great surge in private investment beginning in 1967 created competition, both at the firm and product level. Competition forced more complete and thorough investigation of the solution space of possibilities extant – accelerating the search for the best design. But then the Tax Reform act of 1969 increased the capital gains tax rate from individuals from 25% to 35%, and within three years the effective rate was 49%, and the capital explosion of 67-68 was choked off.

-

Human Resources - In just four years, the number of minicomputer firms exceeded the number of Second Generation mainframe computers ninety-two to sixteen. Many firms could not have existed without a tremendous diffusion of knowledge and training of personnel.

-

Rapid Growth of Buying Demand - Organizations were discovering, and adapting to, economic opportunities from the use of computers (discussed above as Management Information Systems).

In 1984, Bell analyzed the success of the 1968 to 1972 minicomputer start-ups.213 The following table examines the correlation of a company’s origin to its status in 1983.

Exhibit 2.27 Minicomputer Entrants 1968-1983

| Companies | Independent start-ups | Merged start-ups | Existing firms | Related* |

Total | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oligopolistic | 2 | - | 2 | - | 4 | 5 |

| Competitive | 8 | 4 | 2 | - | 14 | 15 |

| Failed | 39 | 6 | 4 | - | 49 | 53 |

| Related * | - | - | - | 25 | 25 | 27 |

| Total | 49 | 10 | 8 | 25 | 92 | 100 |

| Percent | 53 | 11 | 9 | 27 | 100 |

* Non-computer companies building minicomputers for backward integration or special system niches: Again Bell.214

The oligopoly in minicomputers consisted of four firms, or five percent of all entrants. (DEC, IBM, DG and Prime) Over sixty percent of entrants were start-ups. As of 1983, 53% of all entrants had failed and no longer existed.

Minicomputers experienced three generations of product advance before the trajectory reached its sustaining level – 8-bit, 16-bit and 32-bit architectures. In each, a new firm introduced the first commercial success: DEC, DG and Prime respectively. DEC proved able to respond to the challenge of the new architectures, and in each had a dominant design – the PDP-11 and the story yet to be told of the VAX.

By 1976, minicomputers were no longer poor cousins to mainframe computers, but were a high growth market-structure in their own right. In 1976, minicomputers revenues totaled $1.8 billion, still dwarfed by the $10 billion of mainframe computers, but already equal to those of service bureaus at $1.9 billion.215 Minicomputers and dedicated application computer systems (OEMs) represented seven out of every ten computers installed.216 OEM’s remained important, at 40% of revenues and 66% of unit sales, but significantly less so than only a decade earlier when OEM’s accounted for virtually all minicomputer sales.217 The Government now represented less than 5% of all installed computers – down from over 90% in the mid-1950’s.

IBM introduced its first minicomputer, the Series 1, in 1976. IBM’s actions were not motivated by any threat of immediate competition for IBM had $7 billion in revenues, ten times those of either DEC218 or its nearest mainframe competitor, Honeywell. But much as IBM once reacted when insurance companies signed contracts to buy UNIVACs, insurance companies and banks – two of IBM’s largest and best customer types – forced IBM’s actions when they began using minicomputers. (Industry statistics for 1976 show insurance and banking as the two most intensely computerized market-structures at 76% and71%.)219

In 1976, DEC, once again played catch up, only this time it was to ship a 32-bit computer. Despite holding a 40% market share, DEC now lagged Prime Computer, the first to introduce a commercially successful 32-bit minicomputer, by four years. And everyone believed, correctly, that future growth in minicomputers would be in 32-bit architectures, just as it once had been in 8-bit and 16-bit architectures.

Bell, back at DEC since 1975 as vice president of engineering, had a vision larger than just introducing the best 32-bit minicomputer. He wanted to radically reshape DEC’s entire product line. And much like IBM’s System/360 or de Castro’s PDP-X strategies, his goal was one computer architecture to span the entire range of customer requirements. In the spring of 1975, Bell proposed building the VAX-11220 (Virtual Address Extension. The 11 paid homage to the PDP-11 and was an effort to make it seem all one big happy family of computers. Virtual addressing was introduced commercially in IBM’s System/370-145, in September 1970 – and, for all practical purposes, knocked RCA out of the computer business.) In June 1975, Bell reorganized engineering from one central R & D group and engineering groups for each product line into one department totally focused on developing the VAX.221

In October 1977, DEC introduced the VAX-11/780 – described as a 32-bit “superminicomputer.” It had taken two and one-half years to develop, and although six years after Prime had introduced their 32-bit computer, the VAX-11/780 incorporated the latest in semiconductor logic and memory and supported virtual memory. DEC quickly seized market leadership.222 Good, but not yet done. Bell’s vision meant ceasing new development on all product architectures other than VAX. Bell believed the ability of computers to communicate at high-speed with each other was going to revolutionize how computers were designed and functioned. Having only one architecture made networking them together significantly easier which would give DEC the competitive advantage in networking to overtake IBM.223

Others saw the transformational changes coming in computers as well. In 1977, at one of the largest computer trade shows, the National Computer Conference in Dallas, Mark Shepard, Jr., Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Texas Instruments Inc., delivered the keynote address. He too saw a revolution in progress, but the one he spoke of was the impact of the computer on society and the future:

The remarkable fact is that in computing technology…we stand today about the midpoint of a 12 order-of-magnitude change in the nature of the computing world.There is no way we can envision what this kind of change really means. When major, step-function advances are achieved, their potential usually is realized in successive stages. First, we do better the things we already were doing. Next, we do new things. Finally, the advances pervade and change our entire life style and become an essential, built-in part of our society. The computer revolution is just reaching the threshold of this third stage.224

Shepard goes on to add: “The U.S. is clearly ahead in the fundamental technologies which permit the distribution of computing power to the point of use. And with this capability, we can lead an intellectual revolution which will have greater impact on living standards than that of the industrial revolution.”225 Twenty years later, Shepard’s seemingly audacious prediction would become accepted fact.

By the Fall 1978, Bell was ready to advance his vision to upper management. He saw three-tiers of computers – mainframes, minicomputers and personal computers. New computer communications technologies – networking – would make them all work as one. The individual would seamlessly move among the company’s computers and might someday move among computers all around the globe – the “Intergalactic Network” as put forth by Dr. Licklider in the early 1960’s.

Bell argued for a change in DEC corporate strategy:

The essence of the strategy is simplicity through adopting a single architecture. Although superficially it appears to be possible to have numerous architectures that are segmented by size and by market, the user requirements to cross both size and application boundaries are significant. In fact, given that IBM is segmenting its products both by size and application, the main strength of the strategy is to have a single architecture with which a user can be comfortable rather than bounded by a manufacturer segmentation. The most compelling reason for basing the strategy on the single VAX architecture, besides the technical excellence of the product, is the belief that we cannot build the truly distributed computing system of the ’80s with heterogeneous architectures.226

In December 1978, the DEC Board of Directors endorsed the VAX strategy, and with it, Bell’s vision of the future.

History will prove Bell both right, and yet not radical enough, in large measure because of the third technological discontinuity – the microprocessor.

- [185]:

Datamation Jan 1974, p. 74

- [186]:

Rifkin, p. 23

- [187]:

“Taylor, however, wanted Olsen to understand the workings of the commercial world. He told Olsen that only 3 percent to 5 percent of all research engineers ever see their ideas become products. ‘All the excitement,’ he said, ‘is in things that come to production. Production is where the money is.’” Rifkin 21-22

- [188]:

Rifkin, p. 23-24

- [189]:

Wesley Clark, “The LINC Was Early and Small,” ACM Conf, 1986, p.135

- [190]:

C. Gordon Bell, “Toward a History of Personal Workstations , ACM Conf on the History of Persoanl Workstations, 1986, p. 10

- [191]:

Rifkin, p. 13

- [192]:

Rifkin, p. 38

- [193]:

Bell, p. 11

- [194]:

Rifkin, p. 40

- [195]:

Rifkin, p. 41

- [196]:

Rifkin, p. 44

- [197]:

“Tiny computers lead a price decline,” Business Week May 11, 1968, p. 108

- [198]:

“Without a firm structure and knowledgeable managers, such key areas as manufacturing and order processing became logjams. There was no discernible cohesion between the various engineering groups. Product shipments, particularly in the modules business, were often delayed because engineering didn’t coordinate with manufacturing. There were too many small, untethered groups doing their own thing.” Rifkin, p. 51

- [199]:

Rifkin, p. 56-57

- [200]:

Small Scale Integration contained less than 100 components, i.e. transistors. MMI took over between 1966-1969 and contained 1000 components. LSI moved the components density to 10,000 by the mid-1970’s and VLSI took it to 250,000 by the early 1980’s. Chip, p. 124

- [201]:

For an excellent, and thorough discussion of these concepts, please see: “The Rigid Disk Drive Industry: A History of Commercial and Technological Turbulence,” by Clayton M. Christensen, Business History Review 67 : pp. 531-588

- [202]:

Rifkin, p. 91

- [203]:

Rifkin, p. 97

- [204]:

C. Gordon Bell, “The Mini and Micro Industries,” IEEE Computer Oct 1984, p.17

- [205]:

“The OEM form of distribution is particularly suited to start-up companies because a product is not used in any volume until one to two years after the first shipment,” Bell, p. 17

- [206]:

This graph needs refinement – TBD.

- [207]:

Glenn Rifkin and George Harra, “The Ultimate Entrepreneur: The Story of Ken Olsen and DIgital Equipment Corporation,” Contemporary Books 1988, p. 103

- [208]:

Which also means the most succesful LSI computer, for 16-bits was the maximum level of complexity possible in LSI. The 32-bit computer is VLSI technology.

- [209]:

Glenn Rifkin and George Harra, “The Ultimate Entrepreneur: The Story of Ken Olsen and DIgital Equipment Corporation,” Contemporary Books 1988, p. 103

- [210]:

Gene Bylinsky, “The Computer’s Little Helpers Create a Brawling Business,” Fortune Jun 1970, p. 140

- [211]:

Ibid.

- [212]:

Datamation, May 15, 1971, p.

- [213]:

“The Mini and Micro Industries,” C. Gordon Bell, Computer Oct 1984, p. 16

- [214]:

“The Mini and Micro Industries,” C. Gordon Bell, Computer Oct 1984, p. 16

- [215]:

“Remote Computing Service of In-House Computer?,” Datamation April 1978, p. 93

- [216]:

Ibid., p. 104

- [217]:

OEM’s bought systems for $28,000 on average compared to end users who paid $85,000. “The Minicomputer Boom in 1978,” Mini-micro Systems July 1978, p. 66

- [218]:

“As it celebrated its twentieth birthday in 1977, DEC hit the $1 billion mark in sales. From the year Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company changed its name to IBM in 1924, the company took thirty-three years to attain the billion-dollar plateau.”Rifkin, p. 166

- [219]:

Ibid., p. 100

- [220]:

Rifkin, p. 153

- [221]:

Rifkin, p. 153

- [222]:

Bell, p. 17

- [223]:

Rifkin, p.176

- [224]:

Ibid. D Feb 78, p. 105

- [225]:

Ibid. D Feb 78, p. 105

- [226]:

Rifkin, p. 177