Chapter 2 - Background

2.5 The Institutions of Corporate Capitalism

The period from 1880 to World War I is known as the Second Industrial Revolution.123 Deservedly so, for in that short span of years the industrial economy of the United States changed radically. The small, owner-managed businesses of competitive capitalism were overwhelmed by the coming of large, publicly-traded corporations coalescing to oligopolies and corporate capitalism. Concurrently, the locus of corporate control was shifting from the states to a combination of Federal institutions and market forces. Big Business certainly co-evolved with Big Government; where Big Government was Federal authority and growth in use of agencies. Big Business also meant big investments, investments that necessitated access to capital. Financial markets would come to replace the states in granting, and policing, corporation capital. Contemporaneously, corporations also become recognized by the Constitution as persons, persons being managed by individuals acting as agents, no longer directly by the owners. Amidst these shifting times, AT&T was founded, locking into the strategy and structure it would retain for nearly seventy years, and the national telecommunications network assumed its dominant design architecture.

The beginning of the end for competitive capitalism dates to 1872 when John D. Rockefeller, chief executive of the largest petroleum refiner, Standard Oil Company, led the organization of the National Refiners Association.124 It was an effort by the largest competitive refiners to coordinate collective behavior to escape, or at least moderate, the problems of increasing output and decreasing prices then crippling their industry – problems made worse by the weakening economy. Rockefeller believed that the refiners needed to act in unison to bring order to their competitive conditions. So just as others which had tried to coordinate collective behavior before them – telegraphy (Six Nations 1857)125 and railroads (Saratoga Conference 1873),126 and even the body politic (Articles of Confederation 1781-1788) – the petroleum refiners tried to effect collective behavior, and failed. The Association simply lacked the authority to make the difficult decisions that were the source of operating efficiencies and profitability, such as closing plants and building fewer, and significantly larger, plants.

Not to be deterred, Rockefeller and Standard Oil next negotiated favorable railroad contracts to transport oil, and then formed an alliance of refiners to participate with them. To insure success of the alliance, Standard Oil exchanged its stock for stock of each participating corporation. But at the time, corporations could not hold stock of other companies except by special charters or by virtue of being affected with a public interest (railroads, telegraphs, and public utilities). The trustees of the trusts formed to hold the stock were then current Standard Oil shareholders; as late as 1879, Standard Oil had only forty-one shareholders.127 By 1881, alliance members controlled 90% of the refining capacity of the industry, and Standard Oil, through an extensive series of trusts, held a majority of the shares of stock of the alliance members.

In reaction to Standard Oil’s actions, crude oil producers constructed a pipeline to circumvent Standard’s railroad lock-out, which forced Standard and the alliance to construct pipelines of their own. To optimize use of the jointly owned pipelines meant making mutually dependent decisions about which refineries to close and where to build new ones. No longer would simple coordination suffice, the twenty-six companies128 needed to act as one. At the same time, Standard Oil, with assets in thirteen states and several foreign countries,129 found itself under attack in Pennsylvania where the state was attempting to tax not only the assets of foreign corporations held in the state, but foreign corporation properties held everywhere. Again, the issue was how best to organize – to both operate effectively and avoid state harassment.

Creating one corporation to hold all of its assets was not an option. Corporations could not hold stock in corporations of other states – foreign corporations were the enemy, never were they to be allowed to control state corporations. After much work, Standard Oil’s executives determined they had three ways of legally organizing to effect common corporate ownership with centralized executive authority: form a holding company, an unincorporated joint-stock company, or a trust.130 New York was the only state granting holding company charters, but to secure such a charter required special legislative action. Standard Oil rejected the holding company as too difficult to obtain. The problem of the unincorporated joint-stock association, also available in New York, brought a loss of financial privacy, a sacrifice they were unwilling to make. Therefore, they decided to undertake “a careful development of the plan of holding stocks in trust, while the business was managed by elected representatives of the beneficiaries.”131

On January 2, 1882, Standard Oil innovated a new form of business organization when it formed the Standard Oil Trust under the laws of the State of Ohio. Each trust and corporation of the alliance exchanged their stock certificates for Standard Oil Trust certificates, and agreed to have their separate companies run as if one: “in a manner….most conducive to the best interests of the holders of the said trust certificates.”132 Nine trustees, under the leadership of John D. Rockefeller, were appointed to supervise the combined investments, and became the executive “management” of the collective companies.133 (The properties put into the trust were valued at $70 million, that is $70 million of trust certificates were issued, yet the net book value of the assets totalled only $55 million – the difference can be thought to represent the earnings potential of the company, although at the time the practice was known as watered stock.134 ) Among the first acts of the Trustees were to organize corporations in any state where the Trust had property to hold title to all property in that state. In this way, no property would be held by foreign corporations and thus subject to state acts.

The Standard Oil Trust represented a new means of owning private property. It also distinguished the role of agents from owners. The separation of stewardship from ownership is known as agency.135 Agency emerged naturally when owners of corporations ceased being management, and management ceased being owners. As a consequence, a conflict of interest developed – agents might not always act in the owners’ best interest, but their own. This issue was less important in the case of the Standard Oil Trust because Rockefeller remained both executive officer and a very significant shareholder.

Based on the operating results of Standard Oil from 1882 and 1885, the reorganization worked. Management achieved sought for economies of scale by reducing the number of refining units from fifty-three to twenty-two, concentrating output in three refineries, and scheduling total throughput as one operation.136 The average cost of producing a gallon of refined oil fell from 1.5 cents to .5 cents, with the costs of production in the newer, and larger, refineries even lower.137 Gaining scale had brought economic savings. Those in other industries then saw the advantages they thought existed for them as well.

Standard Oil Trust became the first Big industrial Business, as distinct from the railroads and telegraph. It was also the first trust. The concept of a trust, the exercising of management control through the owning of certificates rather than real assets, was as if another world to many. But the path had been lit for others to follow. To state advocates, it felt like ceding control of their economic futures to distant strangers. And based on their experiences with the railroads, relationships that had generally started out with state and citizen largess, Big Businesses deserved to be treated with great suspicion if not contempt. Big Business was synonymous with monopoly, the antithesis of cultural values and the basic belief system138 that held market competition to be far superior to monopoly in generating economic growth.

The public expressed outcry over the formation of the Standard Oil Trust. The states and Congress quickly launched investigations: Were corporations evading control by the states without any Federal controls to replace them? What they learned, combined with the public support the investigations impassioned, inspired attorney generals of the states to file lawsuits – known as “quo Warranto” suits – “challenging the legal power of corporations to restructure themselves” as trusts.139 The states viewed themselves in battle with corporations to control the productive capital of society – the right to decide best use of both public and private property. It was a battle the states were destined to lose. In a study comparing the flow of moneys to state governments, such as taxes, with the flow of insurance premiums paid by state citizens to foreign corporations over the period 1880 to 1887, the states collected far less moneys than did the insurance companies. The locus of economic power no longer rested with the polity. Economic power now rested in the fate of corporations. Little wonder the states viewed themselves as victims of absentee landlords.140

The Quo Warranto lawsuits141 to outlaw trusts did not deter others from following Standard Oil – cottonoil refining (1884); linseed oil refining (1885); whiskey distilling (1887); sugar refining (1887); to name but a few.142 Attendant to the efficiencies achieved in all these consolidations were the forced closings of many small, local corporations. The corporations of competitive capitalism were under siege. They too raised the specter of Big Business – large corporations will challenge governments’ control,143 or they will price gouge customers while earning “monopolistic profits.” To those aligned against the trusts, the right of corporations to exist remained rooted in improving local economic conditions for the public good, not in improving the profits of foreign corporations. Giving grit to the cause of those resisting Big Business were the concurrent battles the states had with the original Big Businesses – the railroads.144

The victors of the Munn v Illinois decision in 1877 had fought for the rights of the states to regulate railroads. These Western farmers, Pennsylvania oil producers, Eastern businessmen, and even railroad executives concluded that state-level control of railroads was neither working nor a viable option.145 For help they turned to Congress, and began lobbying for Federal legislation regulating railroads. They argued that only Congress had the authority to regulate interstate commerce, and it urgently needed to do so. For years, the issue stirred debate, but little else.

Then in 1886, the Supreme Court, in deciding Wabash, St. L. & Pac. Ry. v. Illinois, made it clear that state laws could not invade interstate commerce – Congress had that responsibility. But if Congress did not act to regulate interstate commerce, remaining “dormant,” then the police powers of the states gave them the right to regulate railroads, even if there were interstate effects.146

Within four months Congress passed the Act to Regulate Commerce of 1887, better known as the Interstate Commerce Act (ICA).147 The Act had rules: “Section 1 stated that all rates were to be just and reasonable; Section 2 outlawed personal discrimination; Section 3 prohibited undue preference or prejudice; Section 4 prohibited charging higher rates for a shorter haul than a longer haul under substantially similar circumstances and conditions; Section 5 prohibited pooling agreements; and Section 6 stipulated that all rates were to be published and adhered to.”148 It also created an administrative body, the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), to enforce and interpret the written rules in the spirit of the founding ideology. A new institution, the Federal regulation of railroads, had been created. The ICC was the first use ever of an administrative agency, and marks the beginnings of Federal administrative law. The innovation of an administrative agency by the government was in reaction to the realized impossibility of effecting direct legislative control over an activity changing as rapidly as the railroads – it would be the state legislatures having to control corporations all over again. Imagine Congress deciding whether a railroad rate was fair or not?

Once Congress passed the ICA economic uncertainty had been reduced, not completely, but enough to unleash a surge of railroad construction. The increase in mileage in 1887 totalled 12,879 miles, more than any other year, up 60% over 1886 and 332% over 1885.149

The railroads had both resisted and welcomed Federal involvement. The relationship had been somewhat resolved. Not so with industrial corporations, those not affected with a public interest: What protections were provided corporations by the Constitution? If they were not citizens, what were they? In 1886, the question was decided, and no longer did corporations exist as legal artifacts. In Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Company, the Supreme Court opined:150

The defendent Corporations are persons within the intent of the clause in section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which forbids a State to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Two years later, in 1888, the nature of state control over corporations changed forever. For in that year, the State of New Jersey passed a law permitting “holding companies:”151

Any company, incorporated or unincorporated, which is in a position to control, or materially to influence, the management of one or more other companies by virtue, in part at least, of its ownership of securities in the other company or companies.

It made legal the trust form of organization152 – the very same trusts that were the object of state quo Warranto suits.153 New Jersey became a “charter mongering” state currying favor of corporate “promoters”154 because New Jersey needed revenue. So much of New Jersey’s property was owned by the railroads, and thus immune from property taxes by prior agreement, that the state was sinking ever deeper into debt.155 Among all states, New Jersey ranked second highest in level of taxation on real property, yet last in income generated.156 New Jersey broke ranks with the other states because it saw an opportunity to generate needed revenues from incorporation fees and annual franchise taxes, even though to do so meant attracting corporations with grants of ever broader privileges and immunities. Ironically, it was New Jersey’s past largesse to the railroads that now resulted in further largesse to industrial corporations. New Jersey became known as the “traitor state” — or more appropriately, the”State of Camden and Amboy” – in reference to the railroad monopoly they had granted of the same name which had “almost obtained control of the State government.”157

Undeterred, New Jersey passed other laws: corporations could purchase stock of other corporations and any other property with stock of their own; and directors were absolved of any responsibility for knowing the value of assets on any basis other than that presented to them –making it possible for directors to pay any price wanted for other corporations, and issuing whatever stock required.158 Indicative of a discontinuity, no new trusts were ever formed after the enactment of New Jersey’s holding company laws.159 In just two years, by 1890, 1,626 corporations – corporations that wanted to become large, national corporations –had moved their legal home to New Jersey.160

Congress launched hearings on trusts in 1888.161 The Republican party Presidential platform of the same year called for government regulation of monopolies.162 In the following two years, five states enacted laws prohibiting combinations or restraints of trade. To many the clash between the existing state institutions and the desire of corporations to be organized by market boundaries, not state boundaries, was anticipated. For example in 1889, a young Woodrow Wilson, before becoming Governor of New Jersey, wrote in The State: Elements of Historical and Practical Politics:

The plan of leaving to the states the regulation of all that portion of the law which most nearly touches our daily interests, and which in effect determines the whole structure of our society, the whole organic action of industry and business, has some serious disadvantages: disadvantages which make themselves more and more emphatically felt as modern tendencies of social and political development more and more prevail over the old conservative forces. . . . . State divisions, it turns out, are not natural economic divisions; they practically constitute no barriers at all to any distinctly marked industrial regions.Variety and conflict of laws, consequently, have brought not a little friction and confusion into our social and business arrangements.163

Four years later, David Wells, thought by many to be the early Dean of economics, put the rise of trusts and Big Business in terms of how people saw their lives being lived:164

The predominant feeling induced by a review and consideration of the numerous and complex economic changes and disturbances that have occurred since 1873, is undoubtedly, in the case of very many persons, discouraging and pessimistic. The questions which naturally suggest themselves, and in fact are being continually asked, are: Is mankind being made happier or better by this increased knowledge and application of the forces of nature, and a consequent increased power of production and distribution? Or, on the contrary, is not the tendency of this new condition of things, as Dr. Siemans, of Berlin, has expressed it, “to the destruction of all of our ideals and to coarse sensualism; to aggravate injustice in the distribution of wealth; diminish to individual laborers the opportunities for independent work, and thereby bring them into a more dependent position; and, finally, is not the supremacy of birth and the sword about to be superseded by the still more oppressive reign of inherited or acquired property?

On July 2, 1890, Congress finally acted and passed the Sherman Act to control the rise of trusts. It represented the second new Federal institution created by Congress to control the rise of Big Businesses within the short span of three years. Unlike the ICA of 1887, however, the Sherman Act165 called for enforcement not by an administrative agency, like the ICC, but by the Federal Courts. Critical clauses of the Act read:

Section I. Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is hereby declared to be illegal…

Section 2. Every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor…166

The intended effect of the Sherman Antitrust Act, as it is more commonly known, had been changed by the passing of the holding company laws of New Jersey. How much so would soon be known.

The framers of the Sherman Act believed that the states had all the rights and authority they needed to exclude foreign corporations and control corporation governance. If states objected to New Jersey’s more liberal incorporation laws, they simply had to file suit against the outlaw foreign corporations – read New Jersey’s corporations – on the grounds that no state allowed state-based corporations to sell their stock to foreign corporations.167 However, there were now so many foreign corporations in every state, the states found themselves in an uncomfortable bind. To eliminate foreign corporations meant forcing those corporations to choose one of three options: move their operations out-of-state, sell them to a state-based corporation, or close them down. Since forcing operations to move out-of-state, or to close them down were political disasters – loss of jobs, capital investment, and state income – and it was far from certain whether reverting operations to state-based operations would lead to success, or improved consumer benefits, no state filed suit against New Jersey corporations. Instead, the states decided to talk, hoping to find some common ground to guide their actions – to create uniform policies. All the while, more corporations moved aggressively to expand first to state and then to interstate operations, growing in both scale and scope. These expansionist activities, however, required capital, much more capital than they were generating.

In 1891, New Jersey upped the ante again. This time passing an incorporation law permitting corporations to own the stock of other corporations.168 Now New Jersey corporations could own corporations in another state, without having to force the other states’ corporations to become New Jersey corporations. A New Jersey corporation could own them without having to legally terminate them – meaning corporations wanting to merge or combine operations so as to achieve economies of scale and scope, didn’t have to break state law. They had contracted a new economic freedom, and the states had lost their opportunity to undo acquisitions by foreign corporations – by 1894, 280 of the largest corporations in America were organized under New Jersey law.169

An unexpected benefit of using corporations, not trusts, to organize industrial activity, was the use of stock certificates rather than trust certificates, to evidence ownership. Limited public trading of trust certificates had begun, but uncertainties regarding the rights of holders of trust certificates restrained their trade. Stock certificates, on the other hand, were already accepted as a tradable security, with investors practiced at buying and selling railroad and utility stock certificates. With the ever increasing number of corporations issuing stock certificates to buy other industrial corporations, trading of stock certificates expanded rapidly. New certificate holders, many of whom were individuals who really wanted cash, were very willing, even aggressive, sellers of their certificates, thus generating stock trading activity. (In addition, the 1880’s saw a large number of firms that had formed during the 1870’s wanting to transfer ownership.)170 Many of these stocks first traded on the sidewalksoutside the listed exchanges, principally in New York and Boston, in what were known as “curb” markets – transitional between the traditional personal markets for stock certificates and the impersonal markets of the listed exchanges.171

Shareholders benefited from corporations “going public,” and to a lesser extent from being traded in the curb markets, because the price of the shares they held significantly increased, often more than doubling – just because of being publicly traded publicly. That meant corporation capitalization’s were calculated as seven-to-ten times earnings instead of three times.172 In essence, buyers were willing to pay a much higher price per share, if they had the right to sell the stock at any time, and better yet, at any time and at fair market price. This phenomenon was a direct consequence of the rapid expansion in the numbers of shareholders of public companies, shareholders that held far too few shares of stock to have any influence on management. Since these growing legions of shareholders could not evidence their displeasure with management directly, the only recourse they had was to sell their stock – an option only if sufficient stock traded so they could sell at market prices. (The institution of public capital markets for industrial securities emerged initially, therefore, in response to sellers of stock. Over time, as the volume of buyers and sellers grew, and the high valuations buyers were prepared to put on traded corporations persisted, a venue for the direct sale of stock by industrial corporations developed.)

Recognizing that some shareholders wanted safe returns while others wanted to speculate, industrial corporations began using a technique perfected in railroad financing, but never before used with industrial corporations. Rather than issuing just “common stock,” industrial corporations issued both common and “preferred stock.” The preferred stock paid a stated dividend and derived value from having senior rights to the corporation’s assets in cases of bankruptcy. Common stock, on the other hand, although having a par, or stated, value, was priced by the market dynamics of buyers and sellers as a multiple of earnings, not a percentage of asset values. The preferred appealed to the conservative investor, the common to those wanting to speculate. The preferred also held advantage for the existing common shareholders, for preferred stock did not have voting rights. It had all the advantages of converting asset values into cash without entailing any dilution of control to existing shareholders – especially agency control. As a bonus, simply splitting the two forms of value, asset value and market value, led to increases in valuation of the combined stocks of corporations’ by 40 percent173 – roughly the same mark-up as the Standard Oil Trust.

Then in 1893, just as it seemed as though industrial corporations had been given the green light to expand nationally by New Jersey, the means for small new shareholders to buy and sell their stock in curb and public capital markets, and the protections of the Constitution as persons, the economic recovery collapsed. In the early months of that year, a growing number of mercantile failures raised concerns with whether the government had enough gold to honor its credit obligations. It made for uneasy conditions. Then in May, National Cordage, a very prominent industrial corporation with publicly-traded preferred stock, filed for bankruptcy. The markets staged a one day retreat, and a bear market had begun. Then came July 26, 1893, known as “Black Wednesday.” Industrial stocks began posting daily lows,174 ending any market for industrial stocks. The next four years (1893-1897) would become known as the first industrial depression.

When recovery began, in 1897, so did the radical transformation of the industrial economy. To that it is agreed. But why is not. Prices certainly had something to do with it. The period of 1893 to 1895 represents the lingering low in the thirty year fall in prices of 36%.175 Business were being packed together ever tighter, while at the same time, many were trying to expand operations. At some point, the logic goes, the pain of competing would lead to horizontal combinations – mergers among businesses that were directly competitive. It would also lead to other firms combining vertically, either forward or backward, to capture economies of operational efficiencies, not just the economies of doing more of the same. But business combinations were exactly why Congress had passed the Sherman Antitrust Act – to stop corporations from becoming big and monopolistic – the intended, and consequential, results of horizontal and vertical mergers of corporations. A new logic of market competition was needed to justify Big Business.

The problems of declining prices and recurring recessions were also thought to be a result of overproduction.176 Overproduction was a new phenomenon, and ran deeply counter to the principles of market competition of Adam Smith. In natural liberty, supply and demand remained ever in balance – that is overproduction did not persist. But the agricultural world of Smith, and by historical extension, the many small producers of competitive capitalism were losing their grip on the economy. Instead, ever larger corporations were becoming dominant. One way to stem overproduction, it was argued, was to consolidate production in a few firms that would be able to constrain production, raise prices, and restore orderly market conditions. These were economic changes competitive capitalism was meant to resist, not foster.

Another source of stresses on corporations were conflicts with labor.177 Wages in industry had increased by 70% since 1860178 while prices had declined; thus the purchasing power of wages grew even faster than wages. These higher wages would not have squeezed profits if labor productivity had risen yet faster, but it had not. For the decade 1884 to 1894, wages grew five to six times faster than productivity.179 Little wonder then that labor strikes were on the increase as labor sought higher wages and corporations were without the means to pay them. Between 1890-1893, there were 6,153 strikes, up 27% over 1886-1889. (Strikes dropped to 4,668 during the depression years of 1894-1897.) The new technologies of manufacture, and the obvious need to convert factory equipment and operations to electricity, were ending the days when a crafts philosophy could dictate the nature of production. Labor had to be contracted for and managed very differently if the required capital investments in production were to prove profitable.

Much as Adam Smith had provided a new vision of economic growth to replace mercantilism, another new vision was needed to understand ever lower prices and the rise of large corporate enterprises. The vision came in Alfred Marshall’s Principles of Economics (1890) which owes much to William S. Jevons Theory of Political Economy (1871).180 Both dealt with the problem of prices by introducing the concept of marginalism. To achieve low prices required large-scale operations with attendant high sales volumes, volumes large enough to generate margin to cover all fixed costs. Subsequent sales, marginal sales, then had to cover only their variable costs, hence prices could drop appreciably. If sufficient sales did not exist to support as many corporations as wanted to compete, scarcity-induced competition would winnow them down. Some markets might sustain a competitive number of firms for a long time. Most markets, however, seemed to sustain only a few firms – oligopolies. Marginalism provided the economic logic to explain why Big Businesses benefited the public good. A new logic of competition, one justifying large corporations, could replace the supremacy of forced competition.181

In 1895, amidst recession and economic doubts, the Supreme Court made a statement as only it could do. This time the landmark United States v. E. C. Knight Company, an early lawsuit filed under the Sherman Act.182 The Court ruled that the Sherman Act did not apply to manufacturing, but only to trade – “commerce succeeds to manufacturing and is no part of it.”183 Product has to be made before it can be sold. Commerce is the selling, province of Congress. Making product comes under state authority. The Court reaffirmed the states’, not Federal authority, rights to police corporation governance and regulate the structure of industrial corporations. A monopoly through manufacturing, even though a restraint of trade, was for the states to prosecute, not the Federal government – even when American Sugar Refining Corporation, the merger of six state-based corporations, controlled 98% of the sugar business.

In 1896, New Jersey again liberalized their incorporation laws. The general Revision Act essentially ended state control of corporations.184 New Jersey had given away almost all state governance power, and the Courts had circumscribed state power over both commerce and contracts. For the moment, industrial corporations seemed to be free to do what they wanted, immune to either public interest regulation or antitrust legislation. It was as if they had been given the green light to expand wherever they wanted. Reflective of the privileges and immunities in the New Jersey law, 834 charters were granted in 1896, generating nearly $800,000 in filing fees and franchise taxes.185

Communication technologies played a subtle yet significant role in the Second Industrial Revolution which is instructive for the rest of this study. For without the telephone, and the growing ability to connect to anyone else, the transacting of business through first markets, and then within corporations, would have been severely constrained. In 1893 and 1894, the basic patents for the telephone expired. Competition emerged immediately. In 1895, there were 199 new entrants, in 1900, 508. (See Exhibit 2.7 Telephone Statistics)

Exhibit 2.7 Telephone Statistics

| Year | Commercial systems | Mutual systems | Instruments | Rentals ($) | Approximate avg. rental |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1881 | ** | 2 | |||

| 1883 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1884 | 2 | ** | |||

| 1885 | 4 | ** | 330,040 | 1,928,000 | $5.84 |

| 1886 | 5 | ** | 353,518 | 1,902,000 | 5.38 |

| 1887 | 3 | ** | 380,277 | 2,205,000 | 5.45 |

| 1888 | 8 | 1 | 411,511 | 2,245,000 | 5.46 |

| 1889 | 6 | ** | 444,861 | 2,436,000 | 5.47 |

| 1890 | 7 | ** | 483,790 | 2,685,000 | 5.54 |

| 1891 | 8 | 2 | 512,407 | 2,888,000 | 5.63 |

| 1892 | 12 | ** | 552,720 | 3,057,000 | 5.53 |

| 1893 | 18 | 9 | 516,491 | 3,256,000 | 5.74 |

| 1894 | 80 | 7 | 582,506 | 2,271,000 | 3.89 |

| 1895 | 199 | 15 | 674,976 | 1,476,000 | 2.18 |

| 1896 | 217 | 21 | 772,627 | 1,450,000 | 1.87 |

| 1897 | 254 | 32 | 919,021 | 1,598,000 | 1.73 |

| 1898 | 334 | 75 | 1,124,846 | 1,611,000 | 1.45 |

| 1899 | 380 | 84 | |||

| 1900 | 508 | 181 | |||

| 1901 | 549 | 269 | |||

| 1902 | 528 | 295 | |||

| Total | 3123 | 994 |

Note: Commercial systems include all for-profit companies competing with the Bell System, whereas mutual systems were cooperatives in which profit was a secondary concern to telephone service itself.

(AT&T patents expire 1893-1894)

Source: Stehman

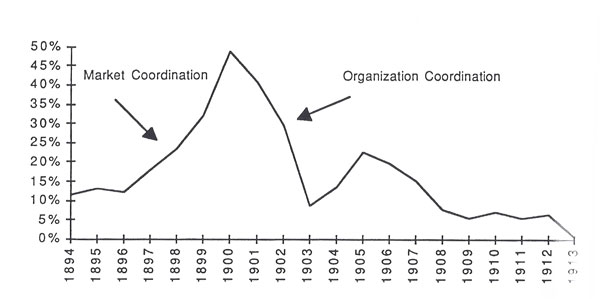

Did competition affect pricing? Yearly telephone rentals of $5.74 in 1893 plunged to $1.45 in 1898. The effect on calls per day was equally dramatic. (See Exhibit 2.8 Growth Rate in Calls Per Day) Calls per day growth up to 1900 can be viewed as communication activity among separate firms trying to conduct business. The precipitous drop between 1900 and 1903 reflects the shift of communication coordination among firms, the market, to within organizations by way of company-based PBX systems. Corporations could consolidate into Big Businesses because the communication technologies made it possible.

Exhibit 2.8 Growth Rate in Calls Per Day

The issue of Who controlled the nation’s industrial structure? loomed large in the presidential election of 1896. William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic candidate, advocated Federal licensing of corporations combined with strong state controls over corporate capitalization and business practices – monopolies would not be allowed. Believing the Supreme Court an accomplice in the rise of Big Business, he argued for a Constitutional amendment giving Congress broader powers to police corporations, and proposed a number of measures to reign in the Supreme Court.186 The Republicans led by William McKinley campaigned against Bryan’s reckless notions to combat corporate growth, and his “free-silver” advocacy, and in the end pulled out the victory.187

Further evidence of the profound shift in society’s acceptance of corporations and their freedom to act was another Supreme Court decision. In Allgeyer v. Louisiana (1897), the Court affirmed the liberty of contract by voiding a state law affecting contractual “property” rights.188 It seemed as long as corporations did not engage in fraudulent acts, they were free to make whatever contractual arrangements they wanted.

By mid-1897, the depression had run its course. As the stock market began to reflect growing confidence in the economy, investors, no longer enamored with the railroads, found they had a new alternative in which to invest – industrial stocks. During the past four years, industrial stocks had performed almost as well as the best railroad stocks, and better than most of them – more than 25% of the railroads by capitalization (and more than 40% by mileage) had gone into receivership.189 During these same four years, the number of publicly-quoted and traded industrial stocks had grown from 30 to 200.190 Doubts as to the investment quality of industrial stocks appeared unfounded – doubts that had stymied marketing of industrial stock certificates but five years earlier. Furthermore, the railroads ceased being large consumers of capital; from year end 1896 to 1904, railroads paid $50 million more in dividends than was the increase in their outstanding common and preferred stock191 – in contrast to consuming hundreds of millions of capital.

By the end of 1897, industrial stocks were poised to explode. Marginalism had shown the way – get Big. The promise of industrial success to those consolidating industry production provided all the justification needed to view speculation in asset values as wise investment.192 No one had any idea what the coming together of economic logic, investment justification, institutional freedoms, and pent up economic potential would mean. In 1897, there were only 8 industrial companies with capitalization’s greater than $50 million – by 1900 there would be 40, and then on to many more. Over the next four years, 1898 to 1902, the value of corporate consolidations totaled 53% of the book value of all manufacturing and mining corporations – $6.3 billion.193 Major merger announcements seemed to happen monthly. By 1903, 2,216 manufacturing plants came under the control of 185 firms.194 By 1904, more than 3,000 firms disappeared.195 Emerging to exercise owner control over these new independent, agency managed, trusts and corporations were investment bankers who dominated the Boards of Directors. Also facilitating this profound change in industrial America between 1897 and 1914, were unprecedented price increases of 40 to 50 percent, an abrupt change from the declining prices of the preceding twenty years, and unique in industrial history.196

In 1898, the prestigious financial firm of J. P. Morgan and Company (known as the “House of Morgan”), the leading underwriter of railroad securities, and headed by J. Pierpont Morgan,197 the most powerful investment banker, i.e. capitalist, of his day, added their approval to the consolidation of industry when they floated the new issue of Federal Steel. Federal Steel was the coming together of thirteen companies and was capitalized at $200 million198 – gigantic for the time. In bringing Federal Steel public, Morgan instituted a new practice that would become universally adopted. Rather than stripping the entities of cash, Morgan made sure Federal Steel had excess cash to finance future growth.

Congress, under pressure to do something about the tide of new large corporations, created the Industrial Commission to “investigate various industrial problems, including corporation evils and the trusts.”199 The Commission recommended a federal agency be formed to publicize improper practices of corporations, hoping that adverse publicity would act as a deterrent. Congress came off as feeble, not for lack of power, but from not knowing what to do, as well as the paralysis that comes from questioning whether anything really needed to be done or not. The depression of 1893-1897 had been devastating, an experience no one ever wanted to reoccur. Large corporations and trusts might be introducing new problems, but they seemed to be pulling the economy out of its lethargy, and to most that was very welcome news.

In 1898 as well, the Supreme Court enumerated what a legal combination was in their decision of Joint Traffic v. United States. The following transactions were not contracts in restraint of trade: “(1) “the formation of a corporation to carry on any particular line of business”; (2) “a contract of partnership”; (3) “the appointment by two producers of the same person to sell their goods on commission”; (4) “the purchase by one wholesale merchant of the product of two producers”; (5) “the lease or purchase by a farmer, manufacturer or merchant of an additional farm, manufactory or shop.”200

The stock market soared 40% in 1899. In the first quarter, new industrial corporations with a capitalized value of $1.59 billion were created – automobile consolidations alone raised $338 million from sale of stock.201 It was unprecedented. Even when a break in the market late in the year led to the bankruptcies of several brokerages, and a panic seemed imminent, Morgan announced he would lend one million dollars on favorable terms to troubled firms and would raise another $9 million if needed.202 The bull market acted as if it had breathed pure oxygen and charged ahead. For the year, new industrial corporations totaling $3.59 billion of capitalized value were created. All these consolidations resulted in a half a million people owning shares of stock in public corporations by 1900.203

A brief story from those turbulent, optimistic times gives an idea of the economic energy being released:

When one of the smaller “trusts” was being formed, a party of steel men were on their way to Chicago one night after a buying tour. The men had been drinking and were in a convivial mood. Said one, “There’s a steel mill at the next station: let’s get out and buy it.” “Agreed!” It was past midnight when they reached the station, but they pulled the plant owner out of bed and demanded that he sell his plant. “My plant is worth two hundred thousand dollars, but it is not for sale,” was the reply. “Never mind about the price,” answered the hilarious purchasers, “we will give you three hundred thousand – five hundred thousand.”204

J. Pierpont Morgan had visions of not simply organizing a few factories, but of restructuring entire industries. In 1901, he led the formation and public flotation of U.S. Steel with a capitalized value of $1.4 billion.205 It represented the consolidation of eleven major firms that had once been 170 separate companies.206 Said another way, it represented “213 different manufacturing plants and transportation companies, 41 mines, 1,000 miles of private railroad lines, 112 ore vessels, 78 blast furnaces and the world’s largest coke, coal and ore holdings.”207 The capitalization consisted of $300 million in bonds, the rest being common and preferred stock. Since the assets of the combined companies only totalled $682 million, the balance, $718 million, was sold as the value of future earnings. To the skeptical, it represented yet another example of watered stock.208 The U.S. Steel transaction accounted for 26% of the capitalized value of all mergers from 1895 to 1904,209 and represented nearly one quarter of the gross national product of the United States in 1901.210

By 1901, New Jersey had become home for 95% of the nation’s major businesses, including Standard Oil, U.S. Steel, and American Sugar Refining Corporation.211 By 1902, the state debt had been paid off and property taxes had been abolished. Three years later, New Jersey had a surplus of nearly three million dollars in its treasury, and the governor proclaimed:

Of the entire income of the government, not a penny was contributed directly by the people…The state is caring for the blind, the feeble-minded, and the insane, supporting our prisoners and reformatories, educating the younger generation, developing a magnificent road system, maintaining the state governments and courts of justice, all of which would be a burden upon the taxpayer except for our present fiscal policy.”212

In September 1901, Theodore Roosevelt became President of the United States when President William McKinley was assassinated. He thought the consolidation of corporate power had gone to far. In his first address to Congress in December, he stated: “In the interest of the whole people, the Nation should, without interfering with the power of the States in the matter itself, also assume power of supervision and regulation over all corporations doing an interstate business.”213 It wasn’t as though Roosevelt was anti-business, he accepted the growth of large corporations to be the natural consequence of industrial development, he did however object to “bad” trusts in contrast to “good” trusts.214 The Roosevelt Administration filed forty-four lawsuits under the Sherman Act, with twenty-two convictions and twenty-two acquittals. (The Taft Administration, 1909-1912, would file ninety Sherman Act lawsuits and win fifty-five convictions.)

In 1902, the states made it clear they simply were not going to act to control large corporations. At the annual meeting of the State Boards of Commissioners for Promoting Uniformity of Legislation, the states abandoned their efforts of the past decade to find common uniform laws they all would adopt. In frustration, the President of the association announced: “It is useless to attempt to secure the adoption of a Uniform Incorporation Act by the various States because the trend of legislation in too many of the States is to enact laws favoring incorporation with a view to pecuniary returns to the State rather than with a view to adherence to sound principles.”215 Further evidence corporations now had the upper hand was a report of the Massachusetts Committee on Corporation Law in 1902 that held: “ordinary business corporation[s] should be allowed to do anything that an individual may do.”216

In that same year, Roosevelt, more certain than ever of the need for Federal action called for a federal law of incorporation and the creation of a Department of Commerce. Congress denied him an incorporation law, but did authorize a Department of Commerce and Labor. In 1903, a wary Congress authorized a Bureau of Corporations to investigate bad businesses. It also passed the Expediting Act that gave priority in the federal courts to cases arising under the Sherman Antitrust Act and the Interstate Commerce Act. Since their passage, both acts had been weakened by court decisions and the ability of offending corporations to stall any decisions by legal delaying tactics. And Congress passed the Elkins Act of 1903 that forbade railroads from giving rebates to large corporations. The Federal government struggled to find a means to stem the perceived power of corporations.

On May 14, 1904, the Supreme Court in Northern Securities Co. v. United States ordered the dissolution of Northern Securities, the merger of “parallel and competing lines across the continent through the northern tier of states.” It signaled that the Supreme Court was willing to employ the powers of the Sherman Act to undo restraining combinations.217 It gave but brief pause to the bull market and merger mania, before the irrepressible consolidations continued. The Northern Securities decision did have the effect, however, of ending calls for a constitutional amendment to deal with the trust problems.

In 1905, Roosevelt told Congress: “experience has shown conclusively that it is useless to try to get any adequate regulation and supervision of these great corporations by state action. Such regulation and supervision can only be effectually exercised by a sovereign whose jurisdiction is coextensive with the work of the corporations – that is, by national government.”218 In 1906, Congress overwhelmingly passed the Hepburn Act. It greatly strengthened the powers of the ICC, including the authority to mandate uniform accounting standards – the first time ever.219 The Justice Department acted as well, filing a lawsuit against Standard Oil for violations under the Sherman Act.

In October 1907, financial panic ended the ten year binge of markets and corporate consolidations. In the process, industrial America had been transformed. Seventy-eight industries were now dominated by firms with more that 50% market share; in twenty-six of them, firms held market shares of more than 80%.220 (There were 171 industries for which information was available;221 suggesting than 46% of American industry was under the control of tight oligopolies.) In 1900, a total of 149 trusts had capitalized values of $4 billion, by 1909 there were 10,020 trusts with a capitalized value of $31 billion.222 (To jump ahead for a moment, these consolidations did not prove permanent; although the dominance of large corporations did persist. (See Exhibit 2.9 Market Shares of Selected Turn-of-the-Century Combinations))

The historic drive to industry consolidation, Big Business, may have been slowed, but not so for Big Government. In 1910, Congress acted again to strengthen the ICC by passing the Elkins-Mann Act. Its provisions made clear that “the ICC was not simply a court nor a branch of the executive but rather a committee, or arm of Congress.”223 The ICC also assumed jurisdiction of the telegraph, telephone, and cable industries.

Exhibit 2.9 Market Shares of Selected Turn-of-the-Century Combinations

| Company | Early Share | Later Share | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Year | % | Year | ||

| Standard Oil | 88 | 1899 | 67 | 1909 | |

| American Sugar Refining | 95 | 1892 | 75 | 1894 | |

| 49 | 1907 | ||||

| 28 | 1917 | ||||

| American Strawboard | 85-90 | 1889 | 33 | 1919 | |

| National Starch Manufacturing | 70 | 1890 | 45 | 1899 | |

| Glucose Sugar Refining | 85 | 1897 | 45 | 1901 | |

| International Paper | 66 | 1898 | 30 | 1911 | |

| 14 | 1928 | ||||

| American Tin Plate | 95 | 1899 | 54 | 1912 | |

| American Writing Paper | 75 | 1899 | 5 | 1952 | |

| American Tobacco* | 93 | 1899 | 76 | 1903 | |

| American Can | 90 | 1901 | 60 | 1903 | |

| U. S. Steel** | 66 | 1901 | 46 | 1920 | |

| 33 | 1934 | ||||

| International Harvester*** | 85 | 1902 | 44 | 1922 | |

| 23 | 1948 | ||||

*Share of cigarette sales

**Share based on steel ingot castings. A weighted average of ten products gives U. S. Steel 57 percent of the market in 1901, declining to 47 percent in 1913. Arthur S. Dewing, Corporate Promotions and Reorganizations (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914), p. 527. U. S. Steel’s share dwindled despite additional large acquisitions in 1904 and 1905.

***Under a 1918 antitrust consent decree, Harvester disposed of its Champion and Osborne lines of harvesting machinery in 1919. These accounted for less than 10 percent of its output of four major implements and a smaller share of all farm machinery. (Source: Simon Whitney, Antitrust Policies (New York: Twentieth Century Fund, 1958). American Smelting and Refining|85-95|1902| |31|1937 Corn Products Refining|90|1906| |59|1914

Source: Yale Brozen, Mergers in Perspective (Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1982) 17.

In 1911, the Supreme Court handed down two of the most important decisions in antitrust history. Standard Oil and American Tobacco were ordered to dissolve.

In January 1914, President Woodrow Wilson delivered his “Trusts and Monopolies” speech to Congress: “I am for big business and I am against the trusts.” Within the year, Congress passed the Federal Trade Commission Act as well as the Clayton Act. The Federal Trade Commission assumed the responsibilities of the Bureau of Corporations and was to provide continuous supervision of competition so as to protect small businesses and keep markets open to new competition. The Clayton Act supplemented the Sherman Act by condemning: “(a) price discriminations, (b) exclusive and tying contracts, (c) intercorporate stockholding, particularly by holding companies and (d) interlocking directorates where the effect of these practices by be substantially to lessen competition or to tend to create monopolies.”224

And then the world plunged into World War I. No longer was the concern of the Federal Government competition, but cooperation, as it needed businesses to supply the products to fight a war. The large corporations of oligopolistic market-structures proved equal to the tasks, and as they won praise for their production prowness, for providing the arms and goods to defend the free world, fears of monopolistic powers subsided, and American settled into its new economic order of corporate capitalism.

Corporate capitalism had supplanted competitive capitalism for reasons reminiscent of the why the Constitution had replaced the Articles of Confederation – economic order and growth was no longer possible under the prior conditions as crises compounded crises. The rich bounty of America’s unspoiled natural resources, combined with rapid population growth, created economic opportunities too large and attractive to be contained within the small, state-based businesses of competitive capitalism. As the technologies of transportation and communication integrated markets, and the technologies of manufacturing drove scale and scope, new, larger economic entities were needed, and being made possible by new technologies and the evolving institutions of capitalism.

It is now time to look more closely at the seminal technology of the telephone, and how its history was impacted by the larger changes described above. Corporate capitalism would not have been possible without the telephone, and the telephone would not have prospered as it did without large corporations. Invented amidst the crisis of competitive capitalism, the telephone grew mature by World War I. Its transformation from the intellectual property of patents, to the private property of a large, publicly-traded corporation, happened simultaneously with corporate capitalism’s emergence and dominance, and thus offers a unique opportunity to observe how corporations reflect the larger forces that operate around them. For example, just as corporate capitalism had to respond to the rise of Federal regulation and antitrust policy, so did AT&T; only AT&T used these institutions to lock in and sustain its monopolistic powers, not be torn down by them. (See Appendix 2.2 Emergence of Corporate Capitalism and AT&T ) Yet during the processes of its self-organization, AT&T seeded structural inertias that eventually became its undoing; a story that will also be told. The principles being explored will be explicated in future chapters, and shown to function over the life cycles of every successful corporation.

But enough, now to return to the depression of the 1870’s, the eve of the crisis of competitive capitalism, and the story of Alexander Graham Bell, the telephone, and AT&T.

- [123]:

TBD Other names

- [124]:

Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., The Visible Hand:The Managerial Revolution in American Business pp.320-324

- [125]:

Thompson, “Wiring”, p. 319

- [126]:

Charles Francis Adams, Jr., “Railroads: Their Origin anbd Problems,” G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1878, p. 150

- [127]:

Ralph W. Hidy and Muriel E. Hidy, “Pioneering in Big Business 1882-1911,” Harper & Brothers New York, 1955, p. 44

- [128]:

Ibid, p. 45

- [129]:

Ibid., p. 42

- [130]:

Harold F. Williamson and Arnold R. Daum, “The American Petroleum Industry,” Northwestern University Press, 1959, pp. 468-469

- [131]:

Williamson, Quote from: Hepburn, Hearings, Report of the Committee, 68. p. 468

- [132]:

Navin and Sears, p112

- [133]:

In essence, the trust was a holding company but with the use of trust certificates and a Board of Trustees instead of stock certificates and a Board of Directors.

- [134]:

Hidy and Hidy, p. 46

- [135]:

See Nathan Rosenberg and L. E. Birdzell. Jr., How the West Grew Rich, for a more thorough discussion.

- [136]:

SS p.73

- [137]:

VH p.324

- [138]:

Acknowledge North

- [139]:

KS p.321

- [140]:

TBD

- [141]:

“By 1890, 27 states had enacted laws to either destroy or prevent trusts and monopolies.”Melvin I. Urofsky, “Proposed Federal Incorporatin in the Progressive Era,” p. 163

- [142]:

Ibid p113

- [143]:

Penn railroad numbers - Chandler

- [144]:

Technically, Western Union was the first national business.

- [145]:

See Skowronek ..rr reg pp. 351-376

- [146]:

EL pp. 685-686

- [147]:

The report of the Senate Commerce Committee on Interstate Commerce of January 18, 1886, known as the Cullom Report, is considered the classical statement of the railroad problem and the need for federal regulation…… The 1886 Cullom Report, upon which the Interstate Commerce Act was built, treated railroads as one part of the overall evolution of transportation and communication as a whole and explicitly discussed telegraph communication in the same general context. Paglin, pp. 26-27

- [148]:

Richard D. Stone’sThe Interstate Commerce Commission and the Railroad Industry:A History of Regulatory Policy: page 6

- [149]:

Statistical Abstract of the United States 1891, p. 263 It is not claimed that all the growth was due to the institutionalization of regulation. See Thomas S. Ulen, “Railroad Cartels before 1887: The Effectiveness of Private Enforcement of Collusion,” Research in Economic History 1983

- [150]:

Gerald Carl Henderson, “The Position of Foreign Corporations in American Constitutional Law,” Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1918, p. 148

- [151]:

“The holding company, like the trust, was a device that provided industrialists with control of the output an pricing policies of several firms engaged in the manufacture of identical products.”K pp.330-331 The holding company allowed for the only activity to be the holding of stock in other corporations; it did not have to be an operating company. Quote from: James C. Bonbright and Gardiner C. Means, “The Holding Company,” McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York and London, 1932, p. 10

- [152]:

NJ p. 571

- [153]:

By 1890, twenty-three states had passed some form of restrictive legislation.

- [154]:

TBD

- [155]:

See NJ for a comprehesive treatment of the story.

- [156]:

NJ p. 568. First year revenue receipts totalled …….PSQ

- [157]:

Charles Fairman, “The So-called Granger Cases, Lord Hale, and Justice Bradley,” Stanford Law Review: July 1953 p. 593

- [158]:

Ibid

- [159]:

TBD

- [160]:

Ibid, p. 573

- [161]:

K p. 323

- [162]:

Frankllin D. Jones, “Historical…..” p.218

- [163]:

Woodrow Wilson, quoted fromThe State:Elements of Historical and Practical Politics, rev. ed. (Boston:D. C. Heath 1900; 1st ed, 1889), 469, 473, cited in Richard Sylla, “The Progressive Era and the Political Economy of Big Government,”Critical Review5 , no. 4 p. 541

- [164]:

David Wells,Recent Economic Changes,pp. 324-5.

- [165]:

The Sherman Act was named for the same John Sherman of Ohio who spearheaded the effort in the 1860’s to introduce market competition into telegraphy with the Act in 1866.

- [166]:

Bork, pp. 19-20

- [167]:

McCurdy, p. 332 “New Jersey holding companies, then, were extraordinarily vulnerable to actions brought in foreign states – so vulnerable, in fact, that a handful of timely lawsuits might have reduced them to mere shells.”

- [168]:

Rosenberg, p202

- [169]:

TBD

- [170]:

navin and Sears, p. 108

- [171]:

Cite North

- [172]:

Sears

- [173]:

Sears, p. 120 Authors note: In 1988, high profile stocks traded at hundred’s of times their asset values, not less than two times.

- [174]:

Robert Sobel, p. 140

- [175]:

Said another way, value added by manufacture in 1899 totalled $5,044 millions, but if it had been valued in 1879 prices, the value would have been $6,252 million – a difference of $1,208 million, or 24% less.

- [176]:

See James Livingston, “The Social Analysis of Economic History and Theory: Conjectures on Late Nineteenth-Century American Development,” The American Historical Review, vol. 92 no.1 Feb. 1987, pp. 69-95. Also Carl P. Parrini and Martin J. Sklar, “New Thinking about the Mrket, 1896-1904: Some American Economists on Investment and the Theory of Surplus Capital,” The Journal of Economic History vol. 63 No. 3 Sept. 1983, pp. 559-578.

- [177]:

See Livingston

- [178]:

Livingston, p. 76

- [179]:

Livingston, p. 78

- [180]:

See

- [181]:

Livingston, pp. 87-88

- [182]:

See K for excellent history

- [183]:

K,p. 308

- [184]:

Urofsky, pp. 163-164 Note 12 The Act”effectively bypassed all or nearly all of the common law restrictions on corporate structure and activity, removed time limits on charters, and allowed firms to engage in just about any business they saw fit to pursue, in New Jersey, in other states, and overseas. New Jersey companies could merge or consolidate at will, set their own capitalization values, and secure the stock of other firms through outright purchase or exchange of their own stock. Moreover, directors now had wide latitude in deciding what information would go to stockholders and in utilizing proxy votes.”

- [185]:

Urofsky, p. 164

- [186]:

John P. Roche, “Entrepreneurial Liberty and the Fourteenth Amendment,” Labor History vol. 4 no. 1, Winter 1963, p. 29

- [187]:

The Democratic platform also include a free-silver plank which, when Bryan was defeated, led to affirmation of the gold standard and resolution of the money issue. These uncertainties had contributed to the depression of 1893-1897. The interested reader is referred to Freidman and Schwartz.

- [188]:

Roche, p. 25

- [189]:

Boskin, p. 218

- [190]:

Navin Sears, p. 127

- [191]:

Source Statistical Abstract 1945. Dividends of $972 million were paid and common and preferred stock outstanding increased $929 million.

- [192]:

Smiley, p. 76

- [193]:

Brozen, p. 7

- [194]:

McCurdy, p. 306

- [195]:

Sobel, p. 156

- [196]:

Freidman and Schwartz, p.135

- [197]:

Morgan, a man of prodigious accomplishments and very much concerned with the need for economic order for there to be social order, saw in the combinations of industrial facilities, as he had earlier of railroad operations, the means to prevent the economic chaos of the previous depression from ever happening again.

- [198]:

Sobel, p. 160

- [199]:

Jones, p. 229

- [200]:

Robert H. Bork, “The Antitrust Paradox,” p.23

- [201]:

Sobel, p. 158

- [202]:

Sobel, p. 153

- [203]:

Baskin, p. 230

- [204]:

from Moody,Masters of Capitalpp. 84-85, cited in Robert Sobel,The Big Board, p. 156.

- [205]:

Sobel, p. 162

- [206]:

Sobel, p. 157

- [207]:

urofsky, p. 161 Note 4

- [208]:

Sobel, p. 162

- [209]:

Sobel, p. 157

- [210]:

Donald O. Parsons and Edward John Ray, “The United States Steel….”,p. 183

- [211]:

Urofsky, p. 164 Note 13

- [212]:

Urofsky, p. 164 Note 14

- [213]:

Urofsky, p. 168

- [214]:

Comment of Darwinianism

- [215]:

McCurdy, p. 340 Note 119

- [216]:

McCurdy, p. 307. Also from Roche, “Entrepreneurial Liberty and the Fourteenth Amendment,” p.31:”In the period from roughly 1890 to World War I a new principle became entrenched in American constitutional law: the doctrine of entrepreneurial liberty. Essentially this doctrine was a break with the common law and the common law premise of the overriding interest of the community, or police power. The right to use one’s property, to exercise one’s calling, was given a natural law foundation – in a philosophically vulgar fashion – over and above the authority of the society to enforce the common weal. The consequence of this doctrine was not alaissez-faireuniverse, but one dominated by private governments which demanded freedom for their activities and restraints on the actions of their competitiors, e.g., trade unions, regulatory commissions, or reform legislatures.”

- [217]:

Jones, p.231 “The effect of the decision was also greatly to encourage government prosecuting and investigating agencies, and to stimulate legal proceedings by the government.”

- [218]:

McCurdy, p. 306

- [219]:

Richard D. Stone, “The Interstate…”, p. 12

- [220]:

Brozen, p. 14

- [221]:

Anthony Patrick O’Brien, “Factory Size…”, p. 646

- [222]:

Sobel, p. 186

- [223]:

Stone, p. 15

- [224]:

Jones, p 364