Chapter 3 - Data Communications: Emergence 1956-1968

3.1 Beginnings of Modem Competition: Codex and Milgo 1956-1967

Starting a company does not always begin with a grand vision of the future. Sometimes the motivation can be wanting simply to do what one enjoys most. Other times it might be the unwillingness to work for others. More often it is some odd combination of reasoning and feeling that is less important that having acted, as if what else would one have done. Such was the case for Jim Cryer and Arthur Kohlenberg in 1962 when their employer, Melpar Electronics, informed them that they were closing the advanced research laboratory they had been running as director and chief scientist, respectively. Even though offered the option to move to Virginia, both men had little desire to leave the Boston area. Rather they believed that they could win technology development contracts being let by government agencies. So they incorporated a new company, Codex, and joined thousands of other companies swept up in the Federal government’s funding of technology innovation.

The early 1960’s were a remarkable period for scientists and engineers with an entrepreneurial itch. Federal government funding for technological innovation seemed bottomless. Following President John F. Kennedy’s challenge in May 1961 to put a man on the moon, funding for advanced technologies surged again, adding to the sizable increases that began after World War II when military spending grew to counter the global threat of the USSR and communism. One of the most important investments in the history of information technologies was the Air Force’s SAGE (Semiautomatic Ground Environment) project; an air defense system undertaken in 1951 to detect Soviet aircraft coming over polar routes. When the USSR launched Sputnik in October 1957, US fear shifted into over-drive. Science and engineering became instant national priorities. In 1958, the ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency) and NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) were created and monies flowed to technology as never before. Then came President Kennedy’s rallying vision in 1961. The large government defense contractors found themselves too busy to compete for every new contract, nor able to maintain technical superiority given the explosion in new technologies. Opportunities lay everywhere for a few scientists and engineers to form a company and win development contracts, even production orders. The Federal Government effectively boot-strapped technological innovation by playing both venture capital investor and ultimate customer.

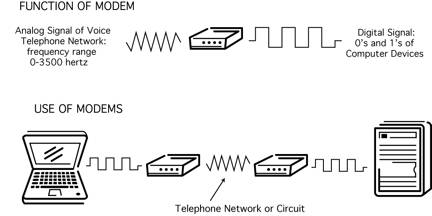

Cryer and Kohlenberg knew just such an opportunity: the Air Force wanted better error-correcting codes for digital transmission over telephone lines. They also knew Robert Gallager, then a young professor at MIT, and his graduate student, Jim Massey, had developed new error-correcting techniques, thought a sure bet to secure a development contract.1 Their instincts were right. Soon they had a contract to develop exotic error-correcting codes for the Air Force’s Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS): the successor to SAGE. BMEWS generated radar data in Northern Canada that was then transmitted over telephone lines to computers in the States. The long telephone lines frequently experienced noise, or worse yet, power outages, that corrupted or destroyed the data being transmitted. Error-correcting codes were needed to restore the lost data. Better codes required more of the total capacity of the communication lines, or bandwidth, leaving less bandwidth for radar data. More powerful codes also stimulated the need for faster modems: the devices that transmit the discrete 0’s and 1’s of digital data, or information, over the continuously varying analog voltage of telephone lines. (See Exhibit 3.1.0 Modem.)

Exhibit 3.1.0 Modem

Modems were first innovated by AT&T Bell Labs for the Air Force as part of the SAGE project. Those modems transmitted data from remote radar sites in Canada to IBM 790 computers in the United States at the speed of 2000 bits per second (bps).2 A paper, “Transmission of Digital Information over Telephone Circuits,” describing this first modem implementation was published in the Bell System Technical Journal in 1955.3 The name modem comes from its function: modulating, or suppressing, information onto a telephone line, and then demodulating, or recovering, the modulated information from the line. The design objective is to accurately transmit as many 0’s and 1’s as possible in a fixed period of time. Since each 0 or 1 is a bit, the convention is to rate modems by how many bits per second (bps) they transmit.4 The faster the modem, the more challenging it is to innovate; particularly with lease-line modems, the ones of interest to Cryer and Kohlenberg.

Modems come in two types: dial-up or lease-line.5 Dial-up modems are used with the public switched telephone network (PSTN, or more familiarly, POTS: plain old telephone system). Lease-line modems are used with leased lines (also known as private or dedicated lines). The distinction is important for dial-up modems make connections when used and only incur telephone line charges for the time connected. The technical challenge arises from the fact that a user may not be using a dial-up modem from the same manufacturer as the one being connected to. Hence, inter-compatibility or inter-operability, and the role of standards, are crucial. Lease-line modems, on the other hand, always remain interconnected over a leased line and bear the cost of the line whether in use or not. Since lease-line modems are invariably from the same manufacturer, standards are less important than are the questions of speed and reliability. The two types of modems require very different technologies to be mastered.

The modem AT&T introduced in February 1958, the Bell System Data Set 103, was a 300 bps dial-up modem. At the time, no one thought 300 bps unduly restrictive as neither computer terminals nor most printers operated at faster speeds. Next AT&T introduced the 1200 bps Data Set 202 series, again dial-up modems. Finally, in 1962, they announced the 2400 bps Data Set 201 series for leased or private-lines.6 Throughout this period, AT&T had little competition. By 1965, however, competition emerged in lease-line modems where AT&T did not posse the monopoly powers they did for dial-up modems. This poised little immediate concern to AT&T as leased lines represented approximately 2 percent of telephone line use.

But speed had mattered from the beginning. Even before taking possession of their first AT&T modems in the 1950’s, the Air Force wanted faster ones. The need for speed came from wanting to create and maintain a worldwide command and control system for air defense. Brigadier General H. R. Johnson, Director of Point to Point Planning for Headquarters Airways and Air Force Communications Systems (AFCS), USAF, from 1950 to 1955, remembers a senior member of his technical staff, Bill Pugh, calculating: “a suitable goal would be 10,000 bits per second in a voice band” for modems. That goal was then set forth in 1956 in: “the proposed General Operational Requirement that AFCS sent to the Air Force, which subsequently became the research document for the Air Force Communications System.”7 Yet a decade later, reliable modems operating at that speed remained an illusive goal.

Such was the background in 1966, when Cryer and Kohlenberg began taking seriously the idea of Codex developing a lease-line modem to sell to the Air Force. That they knew the Air Force yearned for higher speed modems for their air defense system made the opportunity seem a sure bet. Only to-date, they had little experience, or for that matter any real interest, in selling products. Their competence lay in solving difficult technical problems, not in managing what they imagined as the boring business of stamping out the same products, day-in, day-out. The very prospect demeaned Codex’s proud corporate ethos of: “if not technically challenging, it was not worth doing.”8 Even so, Cryer and Kohlenberg worried about Codex’s dependence on the feast-or-famine nature of government contracts; when sales could be $1 million one year and nothing the next. Selling a product, such as modems, did have imagined advantages.

In discussing the subject with MIT’s Gallagher, Cryer and Kohlenberg learned a high-speed 9600 bits per second (bps) modem - four times faster than the fastest commercial modem then available from AT&T - was possible. Wanting to know how, Gallagher told them about Jerry Holsinger, a 1965 MIT Ph.D. graduate whose thesis had been on high-speed data transmission over telephone lines. He last heard Holsinger had left MIT Lincoln Labs and was employed by a small R&D shop on the West Coast named Defense Research Company (DRC). Intrigued, Cryer and Kohlenberg convinced themselves that a 9600 bps modem would give Codex the competitive edge and hopefully the financial security they needed to be successful while upholding their proud tradition of solving hard problems.

On meeting Holsinger in early 1967, Cryer and Kohlenberg discovered he had already formed a company, Teldata, and was soliciting investment from venture capitalists or anyone else who had money. Holsinger claimed he had a working prototype of a 9600 bps modem, one developed at Defense Research Corporation with funding from the National Security Agency (NSA).9 He confided his original design had not worked on normal telephone lines, but he had perfected the design, and had a working breadboard prototype.10 All he needed to do was convert his modem to printed circuit boards to have the world’s first 9600 bps modem.

Holsinger thought of himself as an entrepreneur, not an employee working for a salary or as a research scientist. Only he was having trouble convincing others that they should invest their money with him, not surprisingly given he lacked business experience and was only two years out of graduate school. Cryer and Kohlenberg persuaded Holsinger they were serious about building a modem business and, lacking an alternative, Holsinger agreed to sell Teldata to Codex in May 1967. Codex acquired 82.36% of Teldata’s shares for $94,000.11

Codex embarked on its journey into modems by way of acquisition. Many other defense contractors and electronic companies, like Rixon Electronics, Collins Radio and Stelma, began selling modems, like AT&T had, by using technology they developed for the government. The first independent company really to challenge AT&T, Milgo Electronics Corporation (Milgo), hired a talented individual, Sang Whang, and funded the project internally.

Monroe Miller and Lloyd Gordon, hence the name Milgo, had served the defense agencies and NASA ever since founding their company in 1956. They, like Cryer and Kohlenberg, learned that NASA and military agencies wanted faster modems. In 1965, they hired Sang Whang out of Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute to develop a line of modems to sell to the Kennedy Space Center for down range instrumentation. In 1967, Milgo introduced its commercial 2400 bps modem, the 4400/24PB. Edward Bleckner, head of Milgo’s efforts to enter the modem business, hired an executive search firm to find a seasoned sales/marketing executive with modem experience. They luckily caught up with Matt Kinney on the telephone as he was stranded in an airport by a snowstorm. He remembers:

They asked me if I’d like to come and talk to them about a job, and I said: “Where are you?” They said: “Miami, FL.” The answer: ‘You bet your sweet life!’

In joining Milgo in January 1968, Kinney brought to Milgo needed experience in selling commercial data communication products and an understanding that significant changes might soon propel the demand for data communications; that is, if Tom Carter won his case against AT&T. Kinney remembers:

Tom Carter is one of my oldest and dearest friends. Hell I knew in ‘66 that if Carter prevailed, which seemed highly unlikely at the time, that the industry would take off.12

- [1]:

“Codex - The Early Days,” Multipoint, p.2, Codex publication

- [2]:

Bell Telephone Laboratories, A History of engineering and science in the Bell System: National Service in War and Peace (1925 - 1975), 1978 p.420

- [3]:

This paper indicates the first modem operated at 650 bps, not the 2,000 in “A History of engineering and science in the Bell System.” For many years, AT&T called modems Data Sets.

- [4]:

Baud is a more technical measurement of modem transmission. Input bits to a modem are accepted in groups of bits, from one to six, called symbols. Baud rate is the number of symbols per second transmitted. However, bits per second, or bps, is the preferred convention and the one used herein.

- [5]:

There are other types of modems, but the focus is on telephone modems and the two dominant types by far are dial-up or lease-line.

- [6]:

G.David Forney, Jr., Robert G. Gallager, Gordon R. Lang, Fred M. Longstaff and Shahid U. Qureshi, “Efficient Modulation for Band-Limited Channels,” IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, Vol. SAC-2, No. 5, Sept. 1984, p. 632-633. The 201 was the first synchronous modem; the data is accompanied by the clock signal. The reader interested in a more technical discussion of modems is referred to John A. C. Bingham, The Theory and Practice of Modem Design, John Wiley & Sons, 1988

- [7]:

Interview with author: May 3, 1988

- [8]:

Carr interview with author: April 6, 1988

- [9]:

NSA wanted to transmit digitized speech over telephone circuits using modems.

- [10]:

A breadboard is when the semiconductor logic is wired together, not interconnected with solder as on a printed circuit board.

- [11]:

In June 1968 they acquired the balance of the shares and merged Teldata into Codex.

- [12]:

Kinney interview March 9, 1988. Tom Carter was the aggressor against AT&T in the Carterfone Case (See Chapter 3.2).