Chapter 6 - Networking: Arpanet 1969-1972

6.5 Host-to-Host Software - 1970

The host-to-host group kept growing in members as more sites began to take connecting to the Arpanet seriously. While a core group of graduate students and computer scientists met irregularly, nearly one hundred participants attended bi-annual meetings held on the east and west coast, These meetings were marked by serious arguments, some so heated that the only way to be heard was to shout down the objections of others, as members struggled to come to grip with what they were doing and not doing. There were no answers and even the questions sometimes eluded coherent articulation.

Crocker recalls:

We wanted a generic underpinning, but we didn’t know quite how to get there. We were struggling with it, so the first design we came up with, which we were by this time under some pressure to have, was a specialized design that would allow you to log-in from one place to another, but that was pretty much it.

The tension within the host-to-host group, between creating functional software and the desire to do something special and unique, surfaces in RFC 1000 of 1969: “With the pressure to get something working and the general confusion as to how to achieve the high generality we all aspired to, we punted and defined the first set of protocols to include only remote terminal and file transfer. In particular, only asymmetric, user-server relationships were supported.” The host-to-host group had settled for connecting remote terminals to computers and transferring files - the same application that had frustrated Roberts in his 1966 experiment at Lincoln Labs.

On November 21, when Roberts and Wessler witnessed an initial demonstration of the protocol software by the host-to-host group at UCLA, Roberts could not hide his disappointment. He knew that to win support from reluctant sites for an expanded network would require more functionality than simply logging onto computers at other sites; particularly for those already having computers to log onto. Remote log-in was not a sufficiently compelling application. He had to create a sense of urgency, and more ambitious goals, if the network was to become a reality.

In early December 1969, Roberts met with the host-to-host group in Utah and expressed his dissatisfaction with what had been accomplished and challenged them to be more aggressive. Again from RFC 1000:

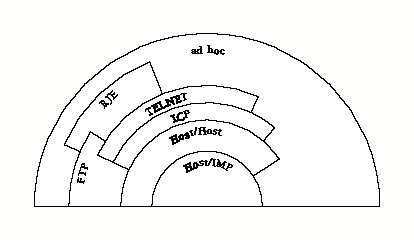

Larry made it abundantly clear that our first step was not big enough, and we went back to the drawing board. Over the next few months we designed a symmetric host-to-host protocol, and we defined an abstract implementation of the protocol known as the Network Control Program. (“NCP” later came to be used as the name for the protocol, but it originally meant the program within the operating system that managed connections. The protocol itself was know blandly only as the host-host protocol.) Along with the basic host-host protocol, we also envisioned a hierarchy of protocols, with Telnet, FTP and some splinter protocols as the first examples. (See Diagram 6.5.0 Layered Relationships of the Arpanet Protocols.)

Diagram 6.5.0 Layered Relationships of the Arpanet Protocols.

Crocker remembers the problem of overcoming the master/slave model of computer communications and the need for layering:

One of the things that was very awkward was up until that time, if you looked at the design of an operating system in a computer, the view implicit in the design was that the operating system was the center of the world, and anything that was attached to the computer was a slave device. You could attach tapes and disks and card readers and printers and so forth, but the initiative was in the computer, and it would say when to talk or when to listen to those things. You try to connect two such devices together, two computers together, and they only know how to talk to each other as if one is the master. Well, if one is the master, then the other must be the slave. We knew that we wanted a much more flexible vision in which the initiative could be at either site, and there would be a coordinated or cooperative model of communications. But the applications that first come to mind, being able to remotely log-in to another thing or to move a file or do remote job entry, all are back in the master/slave model. We wanted those to be special cases, rather than being the only thing you could work with. So we knew that if we put those in as your basic model, that more ambitious things would always be fighting against those kind of things; the business of being able to download a program, of being able to have one machine act as a surrogate for another. So a general-purpose interprocess communication facility was definitely needed, and then you’d build things up on that. We knew we needed layers, but having a number wasn’t important. The fact was that things were built on top of each other, that you had the least commitment at a certain level and then you could build on top of that. Then all of the advanced ideas about how to get computers to cooperate on various tasks could be implemented. Those were the days when, instead of viewing the network as an electronic mail system, which was kind of an afterthought in a way, there were all these visions of shared databases and load balancing, or jobs would be shifted from one machine to another.

By early 1970, the host-to-host group (that had begun as a few graduate students meeting and freewheeling about how the Arpanet might be used) had evolved to a network of over one hundred participants confronting the need to make Arpanet functional without perpetuating modes of computer communications confining the future by the constraints of the past. The need for more formality included recognizing the importance of the host-to-host group. This prompted a name change to the Network Working Group (NWG).

Indicative of the growing awareness of the Arpanet was the involvement of Robert Metcalfe with NWG in 1970. Metcalfe, a graduate student at Harvard looking for a topic for his Ph.D. and a job to make some money, had a friend on the MIT Project MAC offer him a position building memory or working on connecting computers to the Arpanet. Having been told that networking was “hot” as ARPA was pumping a lot of money into it, Metcalfe remembers:

I said: ‘Network,’ but I didn’t know what a network was. I had no idea what a network was!

Metcalfe then learned that ARPA had given Harvard money to connect their PDP-10 to the Arpanet, only they had no one to do it. Metcalfe said he could do it but Harvard was reluctant to turn the project over to an enthusiastic graduate student. Not one to be discouraged, Metcalfe crafted a clever solution:

I went back to MIT and did some wheeling and dealing. I got them to agree that I would, as an employee of MIT, connect their PDP10 to the network and MIT would give Harvard a copy of what I built. I went back to Harvard and I said: ‘Have I got a deal for you!’

Harvard still said no and turned the project over to BBN who in turn turned it over to another graduate student at Harvard. The indomitable Metcalfe began attending host-to-host meetings as a representative from MIT. He remembers:

The Computer Research Lab needed someone to do the networking software for their node of the network. So they said: ‘How would you like to do that?’ I said: ‘Fine.’ And I started going to these meetings which were led by Steve Crocker.