Chapter 6 - Networking: Arpanet 1969-1972

6.8 Early Surprises - 1969-1970

Great promise, modest functionality and pleasant surprises marked the early days of Arpanet. The vision of distributed computing as users and programs utilizing multiple, distributed, concurrent resources, be they other programs or simply computer cycles, remained just promise. The lack of host-to-host protocols, the foundations on which the higher level functions of distributed computing were to be built, limited network functionality. In fact, the only real application remained a primitive version of remote log-in. While instructive, remote log-in did not qualify as a major accomplishment. Even so, early surprises proved the value of the network.

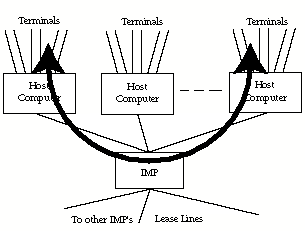

The first surprise was that a user could switch terminal connections between local computers connected to the IMP simply by issuing a command to the IMP. Most terminal traffic never accessed the Subnet but stayed within host IMPs. (See Diagram 4.5 - Intra-IMP Traffic.) Easily switching a terminal connection between local computers was a great benefit to those needed access to multiple computers and reflected the need that would a decade later give rise to networking.

Diagram 6.8.0 - Intra-IMP Traffic

A second surprise was that network users were not frustrated by the lack of functionality; for that is all they wanted - terminal access to remote computers. Roberts remembers:

What I had first expected was that traffic would be computer to computer; it would be transfer of software, the remote use of software, the interaction between machines – that people would be on their own machine doing something and they would need another machine for cycles of something. But it turned out that most people just used the network as an individual terminal on the other machine as a remote terminal. The concept of distributed computing was a future concept in a lot of respects, and the short term need was for a much better communication system to get people to their remote computers.

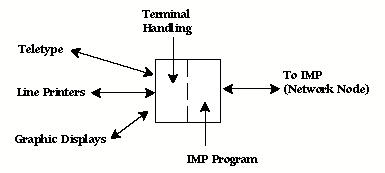

Simply providing terminal access to the Arpanet motivated the innovation of a second type of IMP – the Terminal Interface Processor, or TIP. (See Diagram 4.6 The Terminal Interface Processor.) The advantage of TIPs was that terminals could connect directly to the network via the TIPs without having to connect to terminal ports on a computer to effect network connection. Since computer terminal ports were limited and expensive, tying them up with terminals solely needing network connection was wasteful. Once available, TIPs gave sites without computers access to the Arpanet.

Diagram 6.8.1 The Terminal Interface Processor.

BBN received the contract to develop a TIP in mid-1970 and delivered the first TIP in August 1971. Kahn recalls:

The TIP was a big deal, because now suddenly here you had an IMP, and the question was, how could you hook up these terminals to it. And in fact what we did back then was a mistake necessitated by the economics of the situation. The first IMP’s used 16k of memory. But you could put 32k of memory in the machine. So we used the bottom 16k for the IMP and we use the top 16k for the TIP. The TIP was an IMP that at the front-end was a multiplexer that would allow you to take all these terminals and multiplex them into memory. So that’s really what the TIP was. It was a bunch of software that got written in 16k of memory, plus this multiplexer which we called, at the time, the multi-line controller; that was designed by Severo Ornstein. The TIP connected up to sixty-three terminals to the network. With the TIP, the ARPANET took-off.

The biggest surprise by far, however, was electronic mail, or email. While Roberts believed electronic mail would be an important network application, it never appeared in any of the original specifications, and most admit to being completely surprised. Kahn recalls:

It was email traffic, that was really the dominant traffic pattern. There was a lot of early experimentation, moving graphics back and forth. But in terms of total number of actions people took, there was probably more electronic mail activity, even though some of the other activities probably transmitted more bits.

At first, email consisted simply of a message from one person to another person. But as use grew, the pressure for additional functionality cried out for innovation. Roberts coded one of the first improvements: a “TECO hack” that allowed a user to select which message to read rather than being forced to read messages only in the order received. (TECO (Text Editor and Corrector) was an early editor language. Hack refers to an innovative, yet largely unsupported software program, and is generally a term of respect.)

Dan Lynch, who becomes important later, asserts that Ray Tomlinson and Dan Murphy, both of BBN and authors of TENEX, wrote the original Email program.

Tomlinson and Murphy created Email because they had a PDP10 to themselves to do development of TENEX. They had one machine, a BIG thing, right. Two guys, one machine, and they worked in shifts, I mean they basically worked twelve hours. Twelve on, twelve off, and sometimes they’d overlap, physically, and sometimes they wouldn’t. As soon as they got the file system to the point were it actually would stay together, they started writing notes to each other and leaving them in a place on the disk, and, you know: ‘I did this. This now works.’ Just little notes back and forth and it kept the history. When they reached the point where they had to interface the system to the Arpanet, they said: ‘Oh, well, let’s do it so it works from one machine to another.’ They made that leap because they were writing the network code as well.

Email represented a new mode of interaction and communications: convenient, able to be left by the originator and picked up by the receiver at their convenience, and one did not have to respond immediately to a comment but rather could first give it thought. From the start, email was an informal mode of communication. No one worried about typos or structure. Communications that were short and to the point mattered most.

So even though Arpanet did not initially represent the new paradigm of distributed computing envisioned by Roberts, it made possible a digital community of computer scientists and, with time other users, and, most importantly, it proved packet switching worked.