Chapter 08 - Networking: Diffusion 1972-1979

8.12 Open System Interconnection (OSI) 1975 - 1979

In 1975 the European members of IFIP Working Group 6.1 reluctantly concluded that the Americans were committed to going down the path of TCP. More important, the strategy of the Europeans to influence the CCITT had failed: the CCITT was clearly going to make X.25, a virtual circuit protocol, and a PTT network standard. [50] An X.25 standard, however, left computer users without an end-to-end protocol. Frustrated, yet not without fight, they regrouped and approached the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) to argue their case for end-to-end, or host-to-host, communication standards. ISO, the only international standards organization as powerful as CCITT, was organized as a series of technical committees with specialized sub-committees. Data processing and data communications standards rested with Technical Committee 97 (TC 97). Within TC 97, Subcommittee 6 (SC 6) was responsible for data communications standards and the logical home for the members of IFIP Working Group 6.1. Hubert Zimmerman, a senior member of the French delegation and IFIP, recalls:

We approached Subcommittee 6, explained what we were doing and requested their requirements for going forward with a communication standard for host-to-host communications, or data processing oriented communications standards. There was a low level of acceptance of the message at that time. We were accepted as people, but the ideas did not really get through!

Despite the lukewarm reception, the members of IFIP Working Group 6.1 began working with SC 6, only to find themselves once again embroiled in the politics of technology, not its merits. Again Zimmerman:

We worked with Subcommittee 6 on the definition of the HDLC.51 That was the time when HDLC was just getting out of the oven after ten years of hard work. Now, there was a fair amount of politics in this, and HDLC had been blocked for some time. Until IBM got SDLC through, HDLC couldn’t get through. There was a lot of politics, and we were probably not good enough politicians at that time.

For the Europeans, who hoped TC 97 SC 6 would create end-to-end communication protocol standards, another barrier emerged to test their resolve. Most of them felt they had little choice but to cooperate and push for passage of HDLC, while simultaneously urging SC 6 to take on the challenge of end-to-end protocols. Not all Europeans were prepared to be so compliant however. Acting independently, the British began lobbying TC 97 members to organize a full subcommittee on end-to-end, or as they would become known, “higher-layer” protocols.

With the question of higher-layer protocols scheduled for vote at the upcoming March 1977 SC 6 meeting in Melbourne, Australia, a resolution seemed likely. Unfortunately, the plenary of SC 6 – the decision making body within all ISO committees – rejected the idea, concluding that higher-layer protocols were “not mature enough.”52 Then, a week later, in a stunning reversal, the parent organization, TC 97, decided over the opposition of the U.S. delegation that the higher-layer protocols were sufficiently mature to begin standardization, and authorized the organization of Subcommittee 16 (SC 16) on Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) – a subcommittee equal in status to SC 6. The politics of deciding technological outcomes had birthed a new institution.

The first task of organizing a new subcommittee required appointing a member organization to be secretariat, and then for the selected secretariat to appoint a chairman. (The secretariat handles all subcommittee administrative responsibilities.) A struggle to be secretariat set the British against the U.S. delegations, with the U.S. delegation winning despite having originally opposed the idea of creating the new subcommittee. (The winning argument was that the U.S. held too few ISO secretariats.)

The American National Standards Institute Committee on Computers and Information Processing (ANSI/X3) represented the U.S. in ISO and thus became secretariat. The Systems Planning and Resources Committee (SPARC) of ANSI/X3 authorized a study group, under the initial leadership of Jerry Foley of Burroughs, to form the delegation to SC 16 and create the initial U.S. position paper. Foley in turn recruited Charles, “Charley,” Bachman of Honeywell to the committee despite his having no prior experience with communication protocols. Bachman, who had just completed chairing ANSI/X3/SPARC/DBMS, a study group chartered to investigate the potential for standardization in the area of database management systems (DBMS), had proved his commitment to standards and Foley believed the committee would benefit from his leadership.

Once constituted, the study group had to convince American computer companies to cooperate and create voluntary standards. While opinion divided as to whether standards helped or hurt the economic fortunes of any given U.S. computer company, most executives thought creating standards was a tactic to give foreign companies an opportunity to drive a wedge into the dominant market share held by U. S. companies. As Bachman recalls:

IBM and Burroughs weren’t sure they wanted standards. Honeywell wasn’t sure they wanted standards, except that I said: ‘You do want standards.’ When the issue of participation came up, I said: ‘We should participate.’ They said: ‘No, we’re not sure we want something which is a worldwide standard,’ because they were more concerned about losing sales than getting sales out of it. In fact, the way I got Honeywell involved is that I volunteered to be chairman of the committee. IBM said it was inappropriate to have me as chairman of this group because the chairman should be neutral, sit there, and administer the thing and should not be a protagonist for anything. I was an aggressive chairman!

Bachman, drawing on his DBMS experience, believed standards should focus on interfaces, where components of systems meet. His philosophy is captured in an excerpt from the Summary of the ANSI/X3/SPARC DBMS Framework:

In the course of the early discussions of the Study Group, it emerged that what any standardization should treat is interfaces. There is potential disaster and little merit in developing standards that specify how components are to work. What is proper for standards specification is how the components are meshed; in other words, the specification of interfaces.

Zimmerman, who would become a key member of SC 16, felt resigned to the inevitability of virtual-circuit public data networks.53 Yet rather than demoralizing him, it became a source of motivation. Cerf remembers “Zim’s” state of mind before SC 16 ever met:

I can remember walking down the street in Geneva with Zimmerman in 1977, and he was telling me he was going to start out with virtual circuit oriented stuff because it was the only thing that he could sell in the architecture. He knew, personally I don’t know if he publicly admitted it, but I think he knew, and said so privately, that he wanted to introduce the datagram notions, but it would be later, after everybody was comfortable with the architectural model based on virtual circuits. He was much more politically astute than I was at that point.

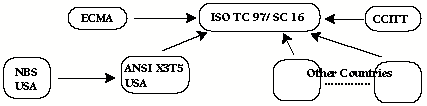

Bachman and Zimmerman would need all the political savvy they could muster for SC 16 would become not only the venue for waging battle over higher-layer protocol standards but a principal coordinating body forging cooperation between ISO and CCITT. To their advantage, the 40-to-50 engineers and scientists who had trekked from INWG through IFIP to ISO constituted much of the membership of the participating country delegations, and had coalesced into a consensus group holding broad agreement on standards-making.54 Testing their resolve would be the presence of invited representatives from CCITT and ECMA – organizations whose members’ economic interests cast shadows over every SC 16 decision and action. (See Exhibit 6.5 SC 16 Organization Structure)

SC 16 first convened in Washington D.C. in March 1978. After concluding the necessary organizational issues, each country presented position papers: every one called for a multi-layer protocol architecture. Given the unanimous agreement, they next established four working groups to distribute the work of creating standards. (See Table 6.0 SC 16 Initial Working Groups) With much accomplished, Bachman suggested they call it a day.

Exhibit 8.12.1 ISO TC97/SC 16 Organization Structure

Only Zimmerman, harden by years of talk and slow action, sought more. He wanted members to commit their agreements to paper and sign the document before the meeting adjourned. Bachman, while thinking the exercise “premature,” said if it could be created then OK. Zimmerman remembers their late night effort:

We remained there in the evening with a few guys, and we started to cut and paste and write down the things. It was probably a twelve-page document in which you had all the basic ingredients of the final version of the Reference Model. We picked seven layers – in some cases some people had organized their stuff in five and six and seven – I think it was the U.S. contribution that put the composition into seven layers. We picked this one because it was not worse than the others, and the others would fit also within this.

The coming-into-being of the OSI Reference Model (Reference Model) benefited from all the knowledge amassed creating computer communication protocols since NCP of Arpanet.55 In segmenting computer communications into logical layers, end-to-end protocols could be assembled by selecting appropriate protocols from each layer to reflect network diversity, while sharing as many intermediate protocols as possible to reduce protocol complexity. Sharing of protocols also meant development and testing could be greatly reduced. (See Exhibit 6.6 The OSI Reference Model) The Reference Model recognized distinct transport and network layers, with SC 16 becoming responsible for the top four layers, the higher-layers, and SC 6 retaining responsibility for the three lower-layers. Hence, the critical coordination between the transport and network layers rested in two committees, a structural separation that would cause future problems.

Table 8.12.2 SC 16 Initial Working Groups

| Working Group | Responsibilities | Chairman | Country of Chair |

|---|---|---|---|

| WG 1 | Overall Architecture | Hubert Zimmerman | France |

| WG 2 | Layers up through Transport | George White | U. S. |

| WG 3 | Upper Layers | Alwin Langsford | U.K. |

| WG 4 | Network Management | Kenji Naimura | Japan |

At variance with then existing practices, the Reference Model represented a framework within which communication standards would fit. It was not a technical standard itself. Done for reasons similar to those that had motivated the speedy adoption of the X.25 standard by the CCITT, the Reference Model was seen as a way to direct market actions and head-off proprietary vendor – or CCITT – standards. For it was the power of the CCITT to dictate the communication protocols computers used (over the public data networks) that posed the most serious threat to the interests of the members of SC 16. In creating the X.25 virtual circuit protocol, and formulating a standard for teletext, an end user application, the CCITT seemed well on the way to locking in how higher-layer applications interfaced to the PTT networks and thus dictating forever how computers interconnected over networks.56

In October 1978, SC 16 met in Paris to resolve requested changes to the Reference Model and finalize a second version. As with the first meeting, key members pulled a near all-nighter to finish the revised document. John Day, a participant in Arpanet Network Working Group (NWG), INWG, and IFIP meetings, was invited by Zimmerman to help formalize the Reference Model for SC 16. Day remembers:

Standards people met from 9:00 to 4:00 and took their leisurely time, and talked the issues; it was an old-boys club, but at those times, while the standards were important, they didn’t have the economic impact, potential economic impact, that this was going to have. So the rules had changed substantially. There was big money involved, and everybody knew it. That’s where the ‘electro-political engineering’ term comes from. Everybody realized that where we drew the lines for the layers, and how we did the technical solutions, determined market lines, determined economics, determined money in somebody’s pocket. It was no longer this nice old-boys club.

Exhibit 8.12.3 The OSI Reference Model

| Layer | Name | Function |

|---|---|---|

| 7 | Application | Selects appropriate service for application |

| 6 | Presentation | Provides code conversion, data reformatting |

| 5 | Session | Coordinates interaction between application processes |

| 4 | Transport | Provides for end-to-end data integrity and quality of service |

| 3 | Network | Switches and routes information |

| 2 | Data | Transfers unit of information to other end of physical link |

| 1 | Physical | Transmits bitstream to medium |

In July 1979, less than eighteen months after being formed, SC 16 transmitted the Reference Model of Open Systems Interconnection to its parent organization TC 97 as a Working Draft. TC 97 speedily approved the Reference Model Working Draft before yearend 1979. Then SC 16 began incorporating suggested changes before resubmitting the Reference Model to TC 97 as a Draft Proposal (DP). TC 97 would then have to approve the Reference Model DP, before sending it to the ISO as a Draft International Standards (DIS). In an auspicious act of cooperation, the CCITT Rapporteur’s Group on Public Data Network Services joined in recognizing the Reference Model.57 With institutions and markets racing to decide the future, communication protocols had become an important.

- [50]:

Larry Roberts and Barry Wessler played important roles in creating the X.25 standard.

- [51]:

High-level Data Link Control (HDLC) was originally designed for multipoint circuits before packet switching had been anticipated. SDLC, Synchronous Data Link Control, was IBM’s comparable protocol.

- [52]:

Hubert Zimmerman

- [53]:

Bachman opines: “Hubert Zimmerman was one of the very most important people on that committee, maybe the most important person, in terms of the contribution to it.”

- [54]:

Pouzin: “By 1977, we had a group of 40 to 50 people in Europe who had been involved in standard making and were also, more or less, a consensus group. We had a sort of lobby that started at the academic level and moved into industry and standard making. This community quickly agreed about the very same principles which were the OSI model and the transport protocols.” (Pouzin, feeling over extended, let others carry his well-accepted ideas forward and remained a member of SC6 .)

- [55]:

Hubert Zimmerman, “OSI Reference Model - The ISO Model of Architecture for Open Systems Interconnection,” IEEE Transactions on Communications, Vol. Com-28, No. 4, April 1980, pp. 424-432

- [56]:

Ibid.

- [57]:

Ibid.