Chapter 08 - Networking: Diffusion 1972-1979

8.3 CYCLADES Network and Louis Pouzin 1971 - 1972

In November 1971, Louis Pouzin joined the Delegation a l’Informatique, an agency of the French government responsible for coordinating all activities related to computing. He would be responsible for creating France’s first computer communication network. His first official act was to travel to the United States and re-establish contacts he had made when at MIT (1962-1965), and to better understand the mysterious Arpanet.19 Pouzin recalls:

I took a round trip to the United States to see how the Arpanet was being developed. I was introduced to the major Arpanet developers including the people at BBN, Larry Roberts, Vint Cerf, the people at SRI, and Len Kleinrock, whom I had known before. I had read the papers on Arpanet before my trip but it looked to me a little bit abstract. I couldn’t really grasp the realities. After my trip to the States, I understood how they started, how they were organized, what the major tasks were in developing the system, and where the deficiencies were. They explained to me all their compromises and the unfinished things they had encountered. We started discussing how to improve that. They understood that I intended to build another network but they really didn’t believe it. They had this feeling that the Arpanet, this kind of complicated system, could only be implemented in a country like the States due to money, expertise and so on. They didn’t believe Europe could bring something like that up.

After returning to Paris, Pouzin began designing the computer communications network and organizing a conference of Europeans interested in networking. Most participants attending the June 1972 meeting were French. Notable exceptions were Steve Crocker of DARPA, Donald Davies of the NPL and Peter Kirstein of University College, London. Two decisions came easy. First, they agreed they needed to meet again and function much like the Network Working Group, NWG, of Arpanet. So they assumed the name of the International Network Working Group or INWG. Second, they agreed the institutional conditions of Europe were very different from those in the United States. How to work with the all-powerful Public Telephone and Telegraph companies (PTTs) and their omnipotent standards-making body, the International Telegraph and Telephone Consultative Committee (CCITT), was bound to be complicated and time consuming. Most attendees believed they needed the credibility and authority of an existing organization to level the playing field. Pouzin, a member of the newly created International Federation of Information Processing (IFIP) Technical Committee 6 (TC 6) on Data Communications, suggested INWG look into affiliating with IFIP, a body of computer scientists interested in international harmony and information sharing organized under the auspices of the United Nations. The INWG members authorized Pouzin to talk with Alex Curan, chairman of IFIP TC-6. They also scheduled the next meeting for November at the University of Kent, England, after the upcoming ICCC demonstration in Washington D.C.

After the meeting, Pouzin returned to his task of designing a simpler packet switching network than Arpanet. In the process, he spent time studying the NPL network and, to the extent he had access to information, the MERIT, TYMNET and INTENET networks.20 Pouzin was certain networking would evolve differently in Europe due to the power of the PTT’s: whereas the monopolistic powers of AT&T were being weakened, the monopolistic PTT’s remained unchallenged. To think a distinct communications network could be superimposed on top of the PTT’s networks, as Arpanet was on AT&T’s, seemed simply naive.

In November 1972, just weeks after the heady experience of ICCC, the workshop at the University of Kent convened. With the Arpanet success serving as both an inspiration to those with computer communication ideas and a proof of principal to be improved upon, workshop organizers hoped to foster new collaborations. Participants from the United States, Canada, Japan and several European countries heard presentations on Arpanet, the NPL of Davies, and the network Pouzin was planning called CYCLADES. (See Exhibit 6.2 The CYCLADES Network.)

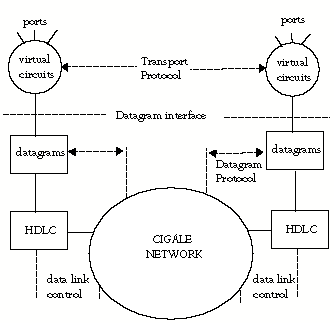

Exhibit 8.3.0 The CYCLADES Network

CYCLADES was to be a pure datagram network. CYCLADES would consist of Host computers connected to packet switches that interconnected using PTT provided telephone circuits. Software in the Host computers would create virtual circuits between Hosts on the network and partition the data to be communicated into datagrams. Hosts would then send the datagrams to their packet switches that forwarded them to the appropriate packet switches that in turn passed the datagrams to their Hosts. The packet switches and the network links were called Cigale - the Subnet in Arpanet. CYCLADES differed radically from Arpanet in that Hosts sent datagrams directly between Hosts and provided end-to-end error correction.

Pouzin used a datagram scheme knowing there was simply no way to impose error correction, or ordering of packet responsibilities, onto the PTT’s. And as had been learned in Arpanet, even if the packet switches communicated error-free, there could be no guarantee that errors were not introduced by communications between the Hosts and the packet switches. Pouzin’s elegant design isolated CYCLADES from the authority and complications of the PTT’s.

In placing responsibility for reliable end-to-end, datagram communications in the communicating computers, and proving the architecture could work, CYCLADES would have continuing repercussions for the future of computer communications. Pouzin recalls his thinking at the time:

The inspiration for datagrams had two sources. One was Donald Davies’ studies. He had done some simulation of datagram networks, although he had not built any, and it looked technically viable. The second inspiration was I like things simple. I didn’t see any real technical motivation to overlay two levels of end-to-end protocols. I thought one was enough.

Pouzin hoped to have CYCLADES working by the end of 1973. By then his would not be the only important network project in Europe. In 1971, the COST 11 Project21 was a multi-nation European initiated research network and a virtual copy of CYCLADES.22 In 1973, COST 11 was renamed the European Informatics Network (EIN) and Derek Barber of NPL became the project director. Closely associated with both CYCLADES and EIN were the leading computer companies of Europe, including Olivetti, ICL, Siemens and CII (Compagnie Internationale pour l’Informatique); firms that recognized if they did not provide an alternative to the PTT’s data communication products, they risked abdicating much of their communications futures. These computer manufacturers composed the core of the European Computer Manufacturers’ Association (ECMA), an organization coordinating mutually advantageous industrial policies.

Not every researcher thought as Pouzin did however. One of his countrymen, Remy Despres, managed the experimental packet switched network of the French PTT called Reseau a Commutation par Paquets (RCP). Announced in November 1973, RCP was based on the PTTs providing virtual circuits and not just communication links. RCP was to serve as a test bed for the public packet network the French PTT’s was planning named TRANSPAC. Despres would find allies the following year in Roberts and Wessler of Telenet who had concluded that Telenet’s packet switching products had to be based on virtual circuits if they hoped to land PTTs as customers. The PTTs could charge more for the reliable transmission of information - that is by providing virtual circuit networks - than simply the provisioning of links.