Chapter 09 - Networking: Emergence 1979-1981

9.16 3Com: Product Strategy and Waiting for a PC

In the spring of 1981, with the fiscal year about to end, management met to set the annual operating plan for the coming year. Krause argued the need to aggressively reduce product costs using semiconductor technology to reduce chip count and printed circuit board space, known as “real estate.” Krause remembers:

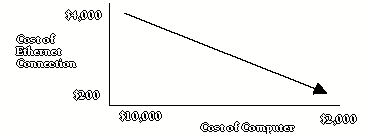

There are very few things that I blew Bob away with, but this was one of them. [See Exhibit 7.3 3Com Learning Curve]. I said: “OK, this is 1981 and this is 1986 and we’ve got to go from here to here.” And Bob said: “What do you mean? How are we going to do that?” So I said: “Well, Bob, first of all, that’s your job, figuring out how we’re going to do it, but if we’re going to make a mass market out of this, and we’re going to connect PCs together, we’ve got to go from here to here, because taking a $2,000 Apple and spending $4,000 to connect it isn’t going to compute. So we’ve got to figure out how to do that. And a way to do that is through semiconductor VLSI integration over time, so let’s start with our Unibus.

Metcalfe agreed. However, when two other new product ideas were suggested, an Ethernet controller for Apple computers – or any of the other existing personal computers – or a terminal server, Metcalfe remained unyielding, quickly ending any discussion. Here Metcalfe’s vision of networking as personal computers networked with Ethernet can be seen as guiding action. Metcalfe considered the existing personal computers as little more than toys. He was certain that sufficiently powerful personal computers would become available, and preferred simply to wait. Even the compelling argument that Ungermann-Bass was growing rapidly by selling terminal servers would not change Metcalfe’s thinking. Metcalfe recalls:

I stubbornly stuck with the idea that, “No, no, no. Connecting terminals to CPUs is a relatively low grade application of my technology.” It was intended to connect PCs together. Our problem was that there weren’t any PCs, or rather the PCs that existed were Apple IIs, which cost $1500 and Ethernet in those days cost $4300.

Metcalfe and Krause recognized their existing products were unlikely to generate enough sales to attain profitability and they had to develop products that had large sales potential and volumes to justify the cost and effort of VLSI.25 To stimulate their thinking, Metcalfe arranged for the two of them to visit both PARC and Stanford. Krause remembers:

Bob was trying to educate me about the Ethernet Gestalt, so he took me over to PARC and wandered me around there, and he took me over to Stanford, and he introduced me to this guy who was working on something called the Stanford University Network.

Exhibit 9.16.1 3Com Learning Curve

Strategizing afterwards, Metcalfe and Krause agreed that the next product 3Com should build was an Ethernet adaptor for Multibus, the bus being employed in the Stanford University Network and favored by those employing the new Motorola microprocessors. While not necessarily the home run they wanted, it leveraged their existing competences and seemed like a solid product to add to their product line and would use the chips they intended to design and develop while they waited for a real PC to be introduced.

- [25]:

VLSI (Very Large Scale Integration) was the next generation semiconductor technology after LSI (Large Scale Integration).